Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing Author Academy is hosting an event over lunch at Hotel Le Meredien, New Delhi . It is to introduce and discuss their self-publishing programme– Kindle Direct Publishing or KDP. The panel will include Sanjeev Jha, Director for Kindle Content, India, Amazon. I will moderate the conversation.

Anyone who is interested in selfpublishing their book online is welcome to attend. It could be a book or a manual  ranging from fiction, non-fiction, self-help, parenting, career advice, spirituality, horoscopes, philosophy, first aid manuals, medicine, science, gardening, cooking, collection of recipes, automobiles, sports, finance, memoir, biographies, histories, children’s literature, textbooks, science articles, on Nature, poetry, translations, drama, interviews, essays, travel, religion, hospitality, narrative non-fiction, reportage, short stories, education, teaching, yoga etc. Any form of text that is to be made available as an ebook using Amazon’s Kindle programme.

ranging from fiction, non-fiction, self-help, parenting, career advice, spirituality, horoscopes, philosophy, first aid manuals, medicine, science, gardening, cooking, collection of recipes, automobiles, sports, finance, memoir, biographies, histories, children’s literature, textbooks, science articles, on Nature, poetry, translations, drama, interviews, essays, travel, religion, hospitality, narrative non-fiction, reportage, short stories, education, teaching, yoga etc. Any form of text that is to be made available as an ebook using Amazon’s Kindle programme.

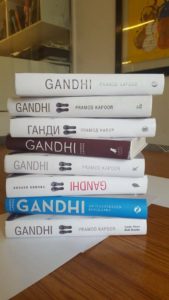

In December 2016 Amazon announced that Kindle books would be available in five regional languages in India — Hindi, Tamil, Marathi, Gujarati and Malayalam. This is a game changing move as it enables writers in other languages apart from English to have access to a worldwide platform such as the Kindle. Best-selling author Ashwin Sanghi called it an “outstanding initiative by Amazon India. It’s about time that vernacular writing moved out from the confines of paperback. It will also enable out-of-print books to be made available now.” Another best-selling author, Amish Tripathi, said this will address the inadequate distribution and marketing of Indian language books, for the much larger market is the one in Indian languages. “I am personally committed to this and am very happy that of the 3.5 million copies that have been sold of my books, a good 500,000 of them are in Indian languages.” Others remarked upon the best global practices it would bring to local publishing.

Sanjeev Jha

Director for Kindle Content, India, Amazon

cordially invites you for a session on

Amazon for Authors:

Navigating the Road to Self-Publishing Success

Hear how Indian authors have used Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) to build and reach audiences across a variety of genres

Date: Thursday, 30 November 2017

Time: 12 -1pm (followed by lunch)

Venue: Hotel Le Meredien, Delhi

This event is free. Registration is mandatory. Please email to confirm participation: [email protected] .

Jaya Bhattacharji Rose

International publishing consultant

It has organised very successful events in Delhi and Kolkatta in the past to showcase the KDP programme. Now in 2017 two events will be organised in Delhi ( 10 Oct 2017) and Mumbai ( early Nov, tbc).

It has organised very successful events in Delhi and Kolkatta in the past to showcase the KDP programme. Now in 2017 two events will be organised in Delhi ( 10 Oct 2017) and Mumbai ( early Nov, tbc).