Deepa Anappara’s “Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line”

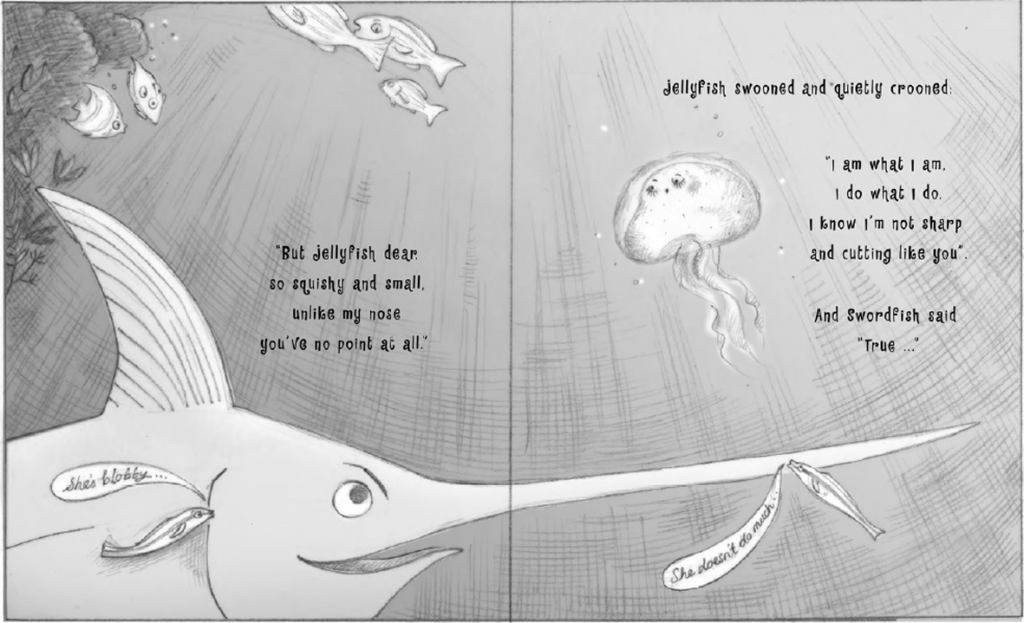

These two are always quarrelling like a husband and wife who have been married for too long. But they cann’t even get married when we grow up because Faiz is a Muslim. It’s too dangerous to marry a Muslim if you’re a Hindu. On the TV news, I have seen blood-red photos of people who were murdered because they married someone from a different religion or caste. Also, Faiz is shorter than Pari, so they wouldn’t make a good match anyway.

Debut author and former journalist, Deepa Anappara’s Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line is set in an urban slum in a nameless Indian city. The story is told from the perspective of nine-year-old Jai. His closest friends in the basti are also his classmates — Pari and Faiz. They are little children who are mostly left to fend for themselves while their parents work for those living in the neighbourhood’s hi-fi apartments. There is a constant undercurrent of violence that is prevalent in this community. These can range from the the sexual assault upon children in the dark alleys to hurling abuses at each other with one of the more favourite curses being called “rat eater” — a reference in all likelihood to the poorest of the poor, lowest in the social pecking order. It is a slum cluster that has people of different communities living together though as the book extract quoted above illustrates that everyone is very aware of the communal differences as well. Slowly over a period of time some of the children begin to disappear. At first given that they are all Hindus, suspicions are cast upon the Muslims living in the basti. But when the young Muslim siblings also disappear, the case begins to puzzle everyone. Unfortunately the communal tensions are exacerbated by now.

Jai and his friends decide to embark upon some of their own detective work to locate the kidnapper. Jai in his innocence coupled with a wild imagination is convinced that this is the handiwork of bad djinns. Nevertheless he is prepared to investigate realising that despite being bribed the policemen are really not interested in helping the affected families. It is not an easy task as the children are strapped for resources, especially finances, making their movement limited. Also they are viewed as poor kids who are not easily trusted by others, so information is not easily forthcoming. It is a challenging situation but the children do their best to find the truth. The novel develops at a steady pace with the focus maintained steadily upon the children while the sinister undertones in the background continue to develop. Whether it is petty politicians, opportunistic self-styled godmen, corrupt police officials, no one really cares for the well-being of the slum dwellers or the abandoned and orphaned kids eking out an existence as ragpickers on the garbage dump, being looked after a benevolent Bottle-Badshah. Yet the unexpected finale of the story comes together brilliantly where it seems fiction merges with reality by bringing up the ghosts of the infamous Nithari crime that was perpetrated upon the children living in the neighbourhood.

It is also extraordinary that Deepa Anappara has chosen to tell the story in a manner that she is probably most familiar with. She unapologetically blends desi words in her English storytelling framework. But the beauty of it all is that the non-English words are never italicised nor is the word or phrase explained immediately after its first appearance. It is a joy to behold this absolute acceptance of “foreign” words. A far cry from when Indian writers writing in English first began to publish novels — inevitably a glossary would be produced. No more.

One of the most obvious critiques of this book in coming days will be of it being a classic example of poverty porn and pandering to a preconceived notion of India. Having said that Deepa Anappara is to be commended for her masterful control of a complex subject. More importantly now that she is based abroad she is able to leverage her position as a woman of colour to write about the poverty back home while at the same time cleverly showcasing the distinct identities of the people and the very real preoccupations that govern daily existence. It could be from social ills such as alcoholism, unemployment, runaway or abandoned children, rampant problem of street children addicted to sniffing glue, lack of basic amenities such as sanitation and water, the poor quality of midday meals served in government run schools which the children yearn for as that is probably the only “proper” meal they will get in the day, high rate of school dropouts inevitably amongst the girls as they are required to be at home looking after their younger siblings, the growing menace of bullies, the manner in which women negotiate these spaces to run their households etc. The lives of the families and friends affected by the disappearance of the children is as traumatic a scenario as it is for you and I. These are people. Not necessarily people who can help prop up an exotic story. This socio-economic analysis that is presented in the garb of fiction without it seeming dreary like a pontificating thesis is not an easy task to achieve. Deepa Anappara manages to negotiate this space well.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line is the Vintage lead for 2020. It was won in nine-strong bidding auction at Frankfurt Book Fair 2018. In a joint acquisition with Penguin Random House India, Chatto & Windus won the UK and Commonwealth rights after a hard-fought auction with eight other publishers. A portion of this novel won the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize, the Deborah Rogers Foundation Writers Award and the Bridport/Peggy Chapman-Andrews Award for a First Novel. This is a greatly anticipated debut that has been endorsed by a galaxy of literary stars such as Anne Enright, Ian McEwan, Chigozie Obioma, Nikesh Shukla, Nathan Filer, Mahesh Rao and Mridula Koshy. Deepa Anappara used to be a journalist in India before moving base to UK. Much of her research for this novel was based on her experience and reading seminal books on urban studies. This book stands apart from many other examples of equally promising debuts in the magnificence of Deepa Anappara’s craftsmanship in creating fine evenly toned fiction — not a mean feat for a debut author. The style of this book is very much akin to contemporary young adult literature. The dark gem of a novel that is Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line fits snugly with much of yalit even with its fairly realistic conclusion. The manuscript may or may not have begun life as yalit which the reading public may never know but it has been positioned as literary fiction. Somewhere the costs incurred in bidding for this book have to be recovered. Despite the yalit genre exploding with an amazing variety of writers, the segment lacks globally recognised literary prizes that will help increase book sales exponentially. But by positioning it as litfic for the trade market, the publishers are ensuring that this novel is eligible for many of the prominent literary prizes in the Anglo-American book market such as the Dylan Thomas Prize for debut writers, the Women Writers Prize for Fiction, the Booker Prize, the Costa First Book Award, National Book Awards etc. By launching it simultaneously across territories too makes this novel eligible for many local prizes. For instance in India there are the Crossword Book Award, JCB Prize, DSC Prize etc to be considered. And as is a truth universally acknowledged that being longlisted or shortlisted for a prize let alone winning it, boosts book sales tremendously. Thereby helping the publisher recover some of their investment costs in winning the auction and spending on the publicity campaign. A win-win situation for the author which in this case is very well deserved.

Do read Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line !

8 Feb 2020