Book Post 28: 18 February – 2 March 2019

At the beginning of the week I post some of the books I have received recently. In today’s Book Post 28 included are some of the titles I have received in the past few weeks.

3 March 2019

When I go to a war zone there’s a certain amount of my own equipment that I take with me. I take my own theatre scrubs and a gas mask, and I take my loupes, which are lenses with four-times magnification that help me perform intricate surgery on small blood vessels and flaps used in plastic surgery. I take a light source, a kind of headlamp, so that I continue to operate when the generators go down or the lights go off, and which also allow me to see deep into the crevices of a wound; and I take my Doppler machine, which allows me to hear the blood flow of the small distal vessels when the arteries do not have enough pressure to give a pulse. I carry it all around in a big, battered old suitcase.

David Notts is an NHS consultant surgeon specialising in general and vascular surgery. Since 1993 he has been taking two months unpaid leave every year from his job to volunteer his services in conflict zones mostly with Medicine San Frontieres (MSF). Over the years he has travelled to the most dangerous parts of the world where there is active conflict. He has worked in areas like Sarajevo, Kandahar, Chad, Gaza, Syria, Haiti, Libya, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Iraq. War Doctor is a memoir focussed primarily on his work as a surgeon in conflict zones though covers some disaster zones as well. He has performed the most complicated surgeries under the most incredible conditions such as with only one bag of blood, no lights, no staff in the operating theatre while the hospital was being bombed. He has witnessed the most horrific wounds perpetrated upon civilians in the name of fighting for a just cause to seeing the ghastly condition of patients in Syria who were being hit by snipers as a part of a game to see who could win a packet of cigarettes. Their choice of targets would vary from day to day. Some days it would be hitting the groins of passers by or another day the bellies of pregnant women. A bullet lodged in the skull of an in-vitro foetus is an unimaginably despicable act but David Nott has had to operate upon such unfortunate victims.

Though there has been no world war since 1945 but the continuously raging conflicts in different parts of the world especially since the 1990s has been relentless. There seems to be no respite with wars of various intensities erupting around the globe. In most cases the war zones Dr Nott has been to have been fiercely fought religious clashes resulting in chilling pogroms. The horrors described in every territory, in every conflict zone, in every nation are numbing. Over the years David Nott has learned to focus on healing and doing the best by his patients irrespective of religion or colour. Yet he has over the years also sensed the growing hostility towards a British/a white man working in the conflict zones while realising he is also exposing himself to the very real danger of being kidnapped and taken hostage, worse still being killed. Anything is possible. In these zones no known rules of civil or military conduct exist or are observed. What exists are enforcement of irrational and arbitrary orders by the two opposing sides of the conflict and this seems to hold true universally for all conflict zones.

David Nott became interested in helping people after he watching the film The Killing Fields about the Khmer Rouge and its pogroms in Cambodia.

What first inspired you to become a war doctor?

Two things. The first was Roland Joffé’s film The Killing Fields, which had a huge impact on me when I saw it as a trainee surgeon. There is a scene in a hospital in Phnom Penh, overrun with patients, where a surgeon has to deal with a shrapnel injury – I wanted to be that surgeon. The second big spur was watching news footage from Sarajevo back in 1993. There was this man on the television, looking desperately through the rubble for his daughter. Eventually he found her and took her to the hospital but there were no doctors there to help her. I thought, “Right, I’m off”. ( War doctor David Nott: ‘The adrenaline was overpowering’, The Guardian, 24 Feb 2019)

David Nott is a seasoned hand at performing surgeries under the most distressful conditions. It has undoubtedly had an impact on his psyche as the near-breakdown he had in the Syrian hospital when reviewing a case, or when a debriefing at the MSF office which should have normally taken 45 minutes took six hours, much of which was spent with him crying. Or when he famously was asked to lunch by the Queen to Buckingham Palace and was unable to speak:

My diminishing ability to cope was rather spectacularly exposed a week later, when I was invited to a private lunch with the Queen at Buckingham Palace. The contrast between those gilded walls and the ravaged streets of Aleppo began doing weird things to my head. I was sitting on the Queen’s left and she turned to me as dessert arrived. I tried to speak, but nothing would come out of my mouth. She asked me where had I come from. I suppose she was expecting me to say, “From Hammersmith,” or something like that, but I told her I had recently returned from Aleppo. “Oh,” she said. “And what was that like?”

My mind filled instantly with images of toxic dust, of crushed school desks, of bloodied and limbless children and of David Haines, Alan Henning and those other western aid workers whose lives had ended in the most appalling fashion. My bottom lip started to go and I wanted to burst into tears, but I held myself together. She looked at me quizzically and touched my hand. She then had a quiet word with one of the courtiers, who pointed to a silver box in front of her, which was full of biscuits. “These are for the dogs,” she said, breaking one of the biscuits in two and giving me half. Together, we fed the corgis. “There,” the Queen said. “That’s so much better than talking, isn’t it?” ( “David Nott: ‘They told me my chances of leaving Aleppo alive were 50/50‘” The Guardian, 24 Feb 2019)

War Doctor is an extraordinary memoir for it details the unforgiving violence that man can perpetrate on his own kind with absolutely no remorse. It does not seem to matter to the people leading the wars that innocent lives and entire cities are being destroyed. David Nott while stitching up patients, performing amputations, delivering babies, watching babies and adults die, visiting morgues that are piled high with bodies that the director of the hospital shows Nott in a matter-of-fact manner, or constantly being drenched in blood gushing out of wounds, collapsing on to the bed in a deep sleep only to wake up and put on shoes and the surgical gown that are caked in blood. After a while the gut-wrenching descriptions of the patients Nott operates upon seem to blur into one another except for the consistency of the massive trauma they have all experienced. The patients he operates upon range from civilians, military personnel to even mercenaries. Descriptions of entire families wiped out by bombs, children orphaned, little infants abandoned with gaping head wounds, teenagers bleeding uncontrollably due to shrapnel wounds, a little boy burning with heat with a possible diagnosis of malaria by Nott which is ignored by the local doctor who insists it is appendicitis and the next time Nott sees the boy with an incision in his abdomen but is in a black body bag parked in the doctor’s changing room for there is no where else to store it in the overflowing hospital! There are some success stories too. For instance when he argued on behalf of an infant to be evacuated to London if she had to survive but was denied permission by MSF, stripped of his credentials with the organisation and permitted to take the risk on his own. He did. The girl survived.

For most of these years spent in the conflict and disaster zones he has been a bachelor with only his parents to be concerned about. Once they too were gone Nott was lonely and was able to focus upon his work with his heart and soul. It was years later when at a fund raiser for Syria he met his future wife Eleanor, then an analyst at the Institute of Strategic Studies, did the enormity of his loneliness sink in. Most likely this manifested itself in his breakdown as for the first time in his life he finally had someone whom he loved dearly to return to in London.

Now he lives in London with his wife and two daughters. He has also established the David Nott Foundation. It is a UK registered charity which provides surgeons and medical professionals with the skills they need to provide relief and assistance in conflict and natural disaster zones around the world. As well as providing the best medical care, David Nott Foundation surgeons trains local healthcare professionals; leaving a legacy of education and improved health outcomes.

War Doctor is a firsthand account of the unnecessary manmade violence and chaos unleashed upon other humans in conflict zones. It is a sobering reminder of exactly how much irrational behaviour man is capable of. The devastating repurcussions on society, on families, on individuals, the wilful destruction of property and the enormous rehabilitation and reconstruction work required to rebuild civil sociey seems to be of no consequence to those who revel in war mongering and in all likelihood participate in it as well. This is a book that must be read by everyone, even those who believe that going to war, performing surgical strikes, are the only way to resolve disputes instead of finding resolutions through peace talks and exploring alternative soft diplomacy tactics such as civil engagement.

Read War Doctor. It will become a seminal part of contemporary conflict literature. It will probably in the coming year be nominated for a literary award or two.

26 February 2019

Nayantara Sahgal (b. 1927) and Toni Morrison (b.1931) have new publications out this past week. Nayantara Sahgal has a novella called The Fate of Butterflies. Toni Morrison’s Mouth Full of Blood is a collection of her non-fiction articles published over the past four decades. Every word chosen in these books is powerful. The two writers have witnessed significant periods of modern history — from the Second World War onwards to experiencing the joy of new democracies and its mantras of self-reliance, new freedoms as those made available with womens’ movements’ and the end of racial segregation, to the presently depressing times of rising ultra-conservative politics, authoritarian rule and sectarian violence. So when Nayantara Sahgal and Toni Morrison as seasoned storytellers pour their wisdom and experience into their writings without mincing words, you listen for the truths they share.

Nayantara Sahgal’s novella The Fate of Butterflies told from the perspective of a political science professor, Prabhakar, is a chilling tale about the all-pervading violence that exists in society. It is an insidious presence that is gradually transforming the rules of social engagement. It is licensing sectarian violence to such a degree that is fast becoming the norm rather than the deviant behaviour it is. The dystopic society Prabhakar finds himself in where people speak of “them” and “they”, mysteriously unnamned groups who are powerful enough to command and strike fear in the hearts of ordinary citizens. The horrors shared in The Fate of Butterflies of mass rapes of women and children, slicing bellies of pregnant women before sexually assaulting them, the homophobic behaviour of some expressed in the horrific violence towards individuals by setting them on fire after trying to castrate them, the quiet disappearance of kebabs and rumali roti from Prabhakar’s favourite dhaba with the excuse that Rafeeq the cook had disappeared making it impossible to offer Mughal cuisine to finding a naked body on the road wearing only a skull cap makes this fiction at times too close to reality. It seems to be a thinly veiled account of many of the witness accounts, oral testimonies and media reports of pogroms and communal violence that have been witnessed in recent years. Linking modern crimes to the historical accounts of Nazi Germany when such horrors unleashed on civil society where first witnessed and documented, Nayantara Sahgal, seems to be reminding the reader of the past being revisited today in the name of “nostalgia” and “harmony” when it is actually a crime against humanity, a human rights violation.

Lopez reminded his friends: no meat unless proven to be mutton, not cow. The Cow Commission went around making sure. He was thinking of becoming a vegetarian himself, he was scared as hell that his fridge might be raided and the mutton turned into beef. Suspects were being dealt with out on the streets, surrounded by camers and cheering beholders. He didn’t fancy that treatment for himself. It was far from reassuring in view of Rafeeq’s disappearance or dismissal. they drank their cloying Limcas, not sure how to find out about Rafeeq. The kaif’s water wasn’t safe and there was no mineral water left. All the bottles of mineral water had been commandeered by ‘them’, the ‘they’ and ‘them’ who came and went, mysteriously unnamed.

Lopez, who taught Modern Europe, said, “This tea party you were at, Prabhu, you said the Slovak was well ahead of the others.’

‘Why wouldn’t he be? They’ve have practice. They had a flourishing Nazi republic during the war, with a Gestapo and Jew-disposal and all the trimmings, and evidently there’s a tremendous nostalgia for those good old days when everybody was kept in line, or in harmony, as they called it.

Togetherness was the watchword. Not that the other speakers weren’t harking back to the glories of the 1930s, but I did get the feeling that some of them were sitting back and waiting to see which way the wind would blow before they risked investing in it. Only fools rush in. Compared with the rest of them the Slovak was the only Boy Scout.’

‘But most people are little people who have to go along with whatever’s happening,’ said Lopez, ‘either because they don’t know any better, or they have no choice and can’t afford to lose their wages or their lives.’

‘Most people,’ repeated Prabhakar, and again with stubborn emphasis, ‘most people everywhere, in Europe or here or anywhere else, only ask to be left in peace to live their lives. It doesn’t seem too much to ask.’

Toni Morrison’s A Mouth Full of Blood is a collection of her essays, speeches and meditations. They are a testament to her varied experiences in American history and literature, politics, women, race, culture, on language and memory. These are structured essays to occasional pieces of writing to moving eulogies as for James Baldwin to her Nobel Prize in Literature speech. It is a wide range of pieces which deserve to be read over and over again but it is the introduction to this volume entitled “Peril” that is exceptionally powerful. It is a commentary on contemporary world politics while focused on the importance of a writer and the significance of making art especially in authoritarian regimes.

In “Peril” Toni Morrison reasons that despots and dictators are no fools and certainly not foolish enough to “perceptive, dissident writers free range to publish their judgements or follow their creative instincts” for if they did, it would be at their own peril. Whereas writers of all kinds — journalists, essayists, bloggers, poets, playwrights — can disturb the social oppression that works like a coma on the population, “a coma despots call peace”. As she astutely points out that “historical suppression of writers is the earliest harbinger of the steady peeling away of additional rights and liberties that will follow”. She continues that there are two notable human responses to the perception of chaos: naming and violence. But she woudl like to add a third category — “stillness”. This could be passivity or dumbfoundedness or it can be paralytic fear. But in her opinion it can also be art.

Those writers plying their craft near to or far from the throne of raw power, …writers who construct meaning in the face of chaos must be nurtured, protected. …The thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being posed, unstaged plays, canceled films — that though is a nightmare. As though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind but wise.” So begins Toni Morrison’s Nobel Lecture in Literature. Likewise pay heed when these two old and wise women speak. Pay heed.

22 February 2019

The Hungryalists: The Poets Who Sparked a Revolution by Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury is an interesting tribute to a short lived but intense literary movement in West Bengal that has left an lasting impact around the world. Their well documented relationship with the Beats poet is also analysed in The Hungryalists. This book will become one of the go-to reads on The Hungryalists precisely for the very reason that little documentation of the movement exists in English as these poets mostly wrote in Bengali. So to transcend languages and cultures requires a bridging language which is English.

The Hungryalist or the hungry generation movement was a literary movement in Bengali that was launched in 1961, by a group of young Bengali poets. It was spearheaded by the famous Hungryalist quartet — Malay Roychoudhury, Samir Roychoudhury, Shakti Chattopadhyay and Debi Roy. They had coined Hungryalism from the word ‘Hungry’ used by Geoffrey Chaucer in his poetic line “in the sowre hungry tyme”. The central theme of the movement was Oswald Spengler’s idea of History, that an ailing culture feeds on cultural elements brought from outside. These writers felt that Bengali culture had reached its zenith and was now living on alien food. . . . The movement was joined by other young poets like Utpal Kumar Basu, Binoy Majumdar, Sandipan Chattopadhyay, Basudeb Dasgupta, Falguni Roy, Tridib Mitra and many more. Their poetry spoke the displaced people and also contained huge resentment towards the government as well as profanity. … On September 2, 1964, arrest warrants were issued against 11 of the Hungry poets. The charges included obscenity in literature and subversive conspiracy against the state. The court case went on for years, which drew attention worldwide. Poets like Octavio Paz, Ernesto Cardenal and Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg visited Malay Roychoudhury. The Hungryalist movement also influenced Hindi, Marathi, Assamese, Telugu & Urdu literature. ( “The Hungryalist Movement: When People Took Their Fight Against The Government” Md Imtiaz, The Logical Indian, 29 June 2016)

*****

With the permission of the publisher here are two short extracts from the book:

Like everywhere else, the shadow of caste hung over the burning ghats as well. There were different burning sections for different castes. The Indian poets accompanying Ginsberg were usually Brahmins. Being there and smoking up was in itself an act of defiance, which normally nobody but the tantrics indulged in. Sunil, who had brought in his dead father here not too long ago, even joked about the place. Later, Ginsberg would go on to write:

I lay in my Calcutta bed, eye fixed

On the green shutters in the wall, crude

Wood that might have been windows

in your Cottage, with a rusty nail

and a ring iron at the hand

To open on heaven. A whitewashed

Wall, the murmur of sidewalk sleepers,

the burning ghat’s sick rose flaring

like matchsticks miles away, my cough

from flu and too many cigarettes,

prophet Ramakrishna banning

the bowels and desires—

War was on everyone’s mind. Ginsberg spoke extensively on what he called the ‘era of wars’. ‘There are as many different wars as the very nature of these wars,’ he had told his fellow poets. Following the death of Stalin and the Cuban Missile Crisis, an uneven calm seemed to have descended, only to be followed by skirmishes here and there. Issues of sovereignty dominated East and West Germany; the Kurds and Iraq were at loggerheads; closer home, the Tibetans were, of course, still struggling to ward off the Chinese invasion of their lands.

Without much ado, Ginsberg, along with Orlovsky and Fakir, arrived one Sunday at the Coffee House looking for Bengali poets. The cafe was abuzz with writers, editors and journalists. Each group had a different table—some had joined two or more tables and brought together different conversations on one plate. But somehow, everyone seemed to have an inchoate understanding of the business of war and what it spelled out for them in the end.

Ginsberg’s arrival was something of a coincidence, Samir mused. Contrary to what one would think was a far-fetched reality, especially in bourgeois Calcutta, a significant number of young Indian students had around that time begun applying for undergraduate courses in American colleges and universities. Times had fundamentally changed, of course. Where once an aspiring middle-class Bengali academic might have chosen to pursue his studies at either Oxford or Cambridge or some university in the Soviet Union, the new mindset now included American universities as the next lucrative biggie to venture forth into. Typically, one would hear snide remarks and private jokes about it in inner circles—about the disloyalty apparent in such choices and more. But those with aspirational values had learnt to live with it, was Malay’s understanding.

Even amid the erratic crowd and the loud voices that drowned everything in coffee, Ginsberg commanded attention. Samir had recalled to Malay:

He approached our table, where Sunil, Shakti, Utpal and I sat, with no hesitation whatsoever. There was no awkwardness in talking to people he hadn’t ever met. None of us had seen such sahibs before, with torn clothes, cheap rubber chappals and a jhola. We were quite curious. At that time, we were not aware of how well known a poet he was back in the US. But I remember his eyes—they were kind and curious. He sat there with us, braving the most suspicious of an entire cadre of wary and sceptical Bengalis, shorn of all their niceties—they were the fiercest lot of Bengali poets—but, somehow, he had managed to disarm us all. He made us listen to him and tried to genuinely learn from us whatever it was that he’d wanted to learn, or thought we had to offer. Much later, we came to know that there had been suspicions about him being a CIA agent, an accusation he was able to disprove. In the end, we just warmed up to him, even liked him. He became one of us—a fagging, crazy, city poet with no direction or end in sight.

All around the Coffee House, there were discussions on war. Would the Chinese Army march up to Calcutta? Would the Indian soldiers hold out? During one of these discussions, Ginsberg spoke with conviction: ‘People who want peace must intervene now, before it’s too late. But, no one will, I’m afraid. Let’s have debates if you will, let’s get talking. Let the Nehrus, the Maos and the Kennedys of this world come together, sit across and talk. Who are we without a debate?’

******

Very early on, the Hungryalists had announced, rather brashly, their lack of faith and what they thought of god. To them religion was an utter waste of time, and they made no bones about this. In fact, in one of their bulletins, they had openly denounced god and called organized religion nonsense. Many of the Hungryalists, with their sharp knowledge of Hindu scriptures, had been challenging temple elders on the different rituals and modes of worship. This came as a shock to many, in a country where religion was very much a part of everyday life—a matter of pride and culture even. On the other hand, Ginsberg was evidently quite taken with religion in India and sought out sadhus and holy men wherever he went in the country. While this might have been because he was in search of a guru, he seemed to be fascinated, in equal measure, by the sheer variety that religion opened for him in India—from Kali worship to Buddhism. But like the Beats, the Hungryalists came together in denouncing the politics of war, which merged with their larger world view.

*****

A tribute to the Hungryalist movement was uploaded on YouTube. It is in Bengali. Here is the film. In the comments Malay RoyChoudhury has also replied.

Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury The Hungryalists: The Poets Who Sparked a Revolution Penguin Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House, an imprint of Penguin Random House, India, 2018. Hb. pp. 190 Rs 599

Further Reading:

Ankan Kazi “Open Wounds: The contested legacy of the Hungry Generation” Caravan, 1 October 2018

Juliet Reynolds “Art, the Hungryalists, and the Beats” Cafe Dissensus, 16 June 2016

“A new book chronicles the radically iconoclastic movement in Bengali poetry in the 1960s” Scroll, 8 Jan 2019

Every Monday I post some of the books I have received in the previous week. This post will be in addition to my regular blog posts and newsletter. Today’s Book Post 25 is after a gap of two weeks as January is an exceedingly busy month with the Jaipur Literature Festival, Jaipur BookMark and related events.

In today’s Book Post 25 included are some of the titles I received in the past few weeks as well as bought at the literature festival and are worth mentioning.

4 February 2019

Renowned Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University, Elaine Pagels Why Religion? is a moving memoir. It is not only an account on the devastating grief she experienced of losing her six-year-old son Mark and husband Heinz Pagels within a year of each other but also of her academic trajectory. A phenomenal academic Elaine Pagels is credited with groundbreaking work in Bible studies. She is one of the earliest scholars to have written on the discovery of the Gnostic gospels.

Why Religion is a memoir that is extremely moving particularly when she discusses the moments of intense pain and grief she experiences. And yet what is remarkable is how she pulls herself together as much as she is able to for the sake of her two younger children, even managing to complete the adoption process for her son David in the absence of Heinz, and making a career move to Princeton University.

She has been awarded some of the most prestigious grants — the Rockefeller, Guggenheim, and MacArthur Fellowships. And this for someone whose initial application to Harvard to do a PhD in the history of religion was rejected saying:

Ordinarily we would admit an applicant with your qualifications. However we are not able to offer a place in our doctoral program to a woman, since we have so many qualified applicants, and we are able to admit only seven to our doctoral program. In our experience, unfortunately, women students always have quit before completing the degree.

But the letter continued to say that if she was still “serious” about doing the course in the following year, the department would grant her admission. So she did.

Her interest in religion began after having visited a Billy Graham event when she was fifteen years old. She was a believer for about a year and a half but then quit it after losing one of her close friends, Paul, in a car accident. She bailed out of evangelical christianity after her friends came to offer their condolences but were unmoved about the incident after discovering Paul was a Jew and not a born again Christian and so he would be damned to hell. Elaine Pagels could not comprehend this as to her mind Jesus Christ was also a Jew.

There are many, many nuggets of wisdom she shares in her memoir. Never is she didactic in her tone but it gives much to think about. Given that she was the product of her times when women were being recognised as individuals in their own right and had much to contribute to society and of course academics, Pagels began questioning the very texts she was studying. Texts that she began to question as being a construct of their times imbued with patriarchy.

One of the earliest passages in the book is:

…the creation stories are old folk tales, they effectively communicate cultural values that taught us to “act like women”. Besides revealing how such traditions pressure us to act, these stories also taught us how to accept the role of women as “the second sex,” a phrase that Tertullian coined in the second century. The same Christian leaders whose scriptures censor feminine images of God campaigned to exclude women from positions of leadership, often hammering on the Bible’s divine sanction of men’s right to rule — views that most Christians have endorsed for thousands of years, and many still do.

This questioning spirit has kept her mentally agile. Consequently the body of work she has published has been pathbreaking not only for Bible studies but also how religious studies are meant to be viewed. She insists upon being a student of the history of cultures that uses faith as a tool to dissect and understand social structures through the ages. “Why Religion?” is also a critical question to be asked today when the world is increasingly polarised along communal lines, making this book even more relevant.

Here is a fascinating conversation with her recorded on 30 November 2018. Pagels is in conversation with Dr. Eric Motley, executive vice president at the Aspen Institute and author of the memoir Madison Park.

Why Religion? is a book that will move you irrespective of whether you are a Christian or not. This is meant to be read by all faiths and non-believers. It is meant for all readers — a fascinating testimony on a life well lived. A life that many folks, ordinary folks live — of living and believing in one’s faith and how these threads co-exist in one’s life, it is impossible to compartmentalise these aspects.

Read it.

3 Feb 2019

Further Reading:

Memories of Heinz Pagels by Jeremy Bernstein ( LRB, 3 January 2019)

“After her son and husband died, Elaine Pagels wondered why religion survives” by Ron Charles ( Washington Post, 6 November 2018)

On 4 September 2017, a group of volunteers led by Harsh Mander travelled across eight states of India on a journey of shared suffering, atonement and love in the Karwan e Mohabbat, or Caravan of Love. It was a call to conscience, an attempt to seek out and support families whose loved ones had become victims of hate attacks in various parts of the country. Along the way they met families of victims who had been lynched as well as some of those who had managed to survive the lynching. The bus travelled through the states, meeting with people and listening to their testimonies. It is a searingly painful account of the terror inflicted in civil society that has seen a horrific escalation in recent months.

The book is clearly divided into sections consisting of an account of the journey based upon the daily updates Harsh Mander wrote every night. It is followed by a collection of essays by people who travelled in the bus. There is also a selection of testimonies recorded by journalist Natasha Badhwar of her fellow passengers. Many of whom joined only for a few days but were shattered by what they saw and heard.

Reconciliation is powerful and it is certainly not easy to read knowing full well that this is the violence we live with every day. The seemingly normalcy of activity we may witness in our daily lives is just a mirage for the visceral hatred and hostility that exists for “others”. It is a witnessing of the breakdown of the secular fabric of India and a polarisation along communal lines that is ( for want of a better word) depressing. Given below are a few lines from the introduction written by human rights activist Harsh Mander followed by an extract by Prabhir Vishnu Poruthiyil. Prabhir who was on the bus is an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Management Tiruchirapalli (IIMT), India. The extract is being used with the permission of the publishers.

Everywhere, the Karwan found minorities living in endemic and lingering fear, and with hate and state violence, resigned to these as normalised elements of everyday living.

…..

Our consistent finding was that families hit by hate violence were bereft of protection and justice from the state. In the case of almost all the fifty-odd families we met during our travel through eight states, the police had registered criminal charges gainst the victims, treating teh accused with kid gloves, leaving their bail applications unopposed, or erasing their crimes altogether.

. . .

More worrying by far was our finding that the police had increasingly taken on the work of lynch mobs. There were tens of instances of the police executing Muslim men, alleging that they were cattle smugglers or dangerous criminals, often claiming that they had fired at the police. Unlike mob lynching, murderous extrajudicial action has barely registered on the national conscience. It is as though marjoritarian public opinion first outsourced its hate violence to lynch mobs, and lynch mobs in BJP-ruled states like UP, Haryana and Rajasthan are now outsourcing it onwards to the police. ( Introduction, p.x-xi)

Prabhir Vishnu Poruthiyil is an assistant professor at theIndian Institute of Management Tiruchirapalli (IIMT), India. He teachesbusiness ethics and his research is focused on the influence of business oninequalities and the rise of religious fundamentalism.

Like many others, I grew up with the usual doseof religiosity and nationalism. But I was also enrolled in a Hindu school (Chinmaya Vidyalaya) that injected an additional dose of Hindu supremacy. Therewas a short phase in my life (jobless, in my mid-twenties) when I went aboutexploring and trying to understand and justify Hinduism. I am the kind of person who tends to immerse himself fully to understand and make sense of theworld. My exploration brought me in close contact with gurus in various ashrams and bhajan groups. I learned Vedic chanting, studied Hindu theology, and even dallied with the idea of becoming a monk. I interacted with groups and individuals committed to Hindutva and attempted to see the world from their perspective (many remain my friends). I could not put my finger on it then, butI was deeply uncomfortable with what I later realised was unadulterated hatred and a stifling resistance to questioning and reason.

Around this time, in 2004, I was admitted into a masters and then a PhD programme in the Netherlands. Lectures by my teachers and exposure to the lives of classmates and refugees with personal experiences of life in theocratic regimes accelerated my disgust with religious nationalism of all kinds. Exposure to liberal political philosophy and to Dutch society made me appreciate the benefits of living in a place run on democratic and rational principles. As my education both in and outside the classroom progressed, my fascination with extreme perspectives rapidly diminished andturned into concern and disgust. It was, however, a visit to Auschwitz in 2012 that made me realise how easy it was for a society to be sufficiently intoxicated by supremacist world views to justify the annihilation of those deemed inferior. That a human tragedy on this scale had happened in the same society that had made incredible contributions to art, philosophy and music was unthinkable.

Over time, I have lost what remains of my beliefin the supernatural and purged myself of superstitions. I would now call myself a rationalist or secular humanist. Ibelieve that the irrationality promoted by religion is a barrier to progress and that religion is unnecessary for morality, and not a guarantee of it.

When I returned to India in 2013 to join the IIM, I did not expect religious nationalism to influence my research in, andteaching of, business ethics. My focus was on inequality. With the BJP’s victory in 2014 and the support of the corporate sector for the party, it became impossible to disentangle business ethics from religious nationalism. Istarted research on a paper on how religious nationalism emerges and whatbusiness schools could do to resist its advance.

When the lynchings began, more than thepsychology of the vigilantes and their victims, my sociological interest waspiqued by the nonchalance and even the endorsement of cow-vigilantism by many people I cared for, particularly among my family, friends, colleagues andstudents. Their unwillingness to recognise bigotry for what it was and rejectpolitical leaders who create an atmosphere of hate resembled the attitudes prevalent in Germany during the Nazi era. It disturbed me deeply to see sectarianism slowly taking hold of persons I loved. I started to worry that the possibility of concentration camps being built in India was no longer a gross exaggeration.

In the meantime, I had initiated a conversation with Harsh Mander. I wished to invite him to give a lecture at the IIM inTrichy. When the Karwan e Mohabbat was announced, I felt it was important to take part. I wanted to see for myself and talk about it to my friends and family and to students in my classes. The experience of looking into the eyesof persons who had lost loved ones was emotionally tough. After each meeting, my mind was constantly wondering how human beings could allow such tragedies to happen. A quote by Gandhi kept ricocheting in my brain: ‘It has always been a mystery to me how men can feel themselves honoured by the humiliation of their fellow beings.’

Looking back now, the memories and emotions of my visits to Auschwitz and of the victims of Hindutva are difficult to distinguish. The same helplessness, resentment and fear captured in the countless pictures of Jews subjected to the Holocaust seem to be reflected inthe eyes of the victims of cow-vigilantism. In contemporary India, I worry it may be unnecessary to build a standalone Auschwitz to implement a sectarian agenda. Terror has been decentralised and imposed through a variety of spaces. The entire country now risks being transformed into one large concentration camp.

How do we push back? Being a committed rationalist, my first instinct is to train citizens to use their reasoning and the language of liberalism and human rights to push back against bigotry andreligious nationalism. But the inroads made by Hindu nationalism into thepsyche can make it difficult for liberal vocabularies to reverse. The languageof ‘human rights’ and ‘freedom of speech’ can be branded as alien and hence ridiculed and dismissed. Furthermore, there are studies that show how groups tend to cling more firmly to their beliefs when threatened by outsiders.

Observant Hindus can be convinced more easily that sectarian hate and bigotry goes against the grain of Hinduism. The definition of Hinduism could be expanded to encompass empathy and compassion.This strategy would require formulating something like the liberation theologythat emerged in Latin America to challenge the interlocking interests of thebusiness elite and the top echelons of the Church that perpetuated inequality.

Excerpted with permission from RECONCILIATION:Karwan e Mohabbat’s Journey of Solidarity through a Wounded India, Harsh Mander, Natasha Badhwar and John Dayal, Context, Westland 2018.

The pictures in the gallery are from Karwan e Mohabbat‘s Facebook page.

19 December 2018

Like a white net veil worn over a red saree, or an ivory satin gown sleeve that borders ornate paisley mehndi patterns, the people of Indian origin in South Africa evolved from holding tightly onto the shreds of Indian culture that they came with inside locked boxes and sewn into hemlines. But, like all migrants, or perhaps refugees the world over, evolution is the Holy Grail, the ability to blend into the current social strata. The result became the South African Indian. A mix of names formed and re-formed, and clothing worn and then not worn, and eventually as apartheid was abolished, an identity searched for and still to be found.

Like a white net veil worn over a red saree, or an ivory satin gown sleeve that borders ornate paisley mehndi patterns, the people of Indian origin in South Africa evolved from holding tightly onto the shreds of Indian culture that they came with inside locked boxes and sewn into hemlines. But, like all migrants, or perhaps refugees the world over, evolution is the Holy Grail, the ability to blend into the current social strata. The result became the South African Indian. A mix of names formed and re-formed, and clothing worn and then not worn, and eventually as apartheid was abolished, an identity searched for and still to be found.

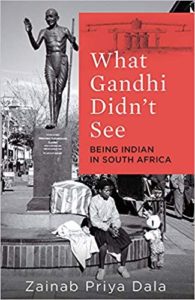

South African writer Zainab Priya Dala’s What Gandhi Didn’t See: Being Indian in South Africa is a collection of essays that are a mix of memoir, sharing opinions on the changing political landscape and the growth of Dala as a writer. These essays are sharply written detailing the complicated histories South African citizens of Indian origin have to contend with on a daily basis. It informs their identity. Even details such as if their ancestors came as “indentured labourers” or as “passenger Indians” makes a world of difference to their sense of identity in a foreign land. Zainab Priya is of mixed parentage as her father is a Hindu and her mother a Muslim. Later she married in to a well-established Muslim business family who had come to South Africa relatively recently but she regularly encounters variations between the families in their habits and living styles.

What Gandhi Didn’t See: Being Indian in South Africa is a slim collection of powerfully written essays. These essays by a South African Indian reflecting upon multiple aspects of her existence is much like this book being the sum of many parts of her life — mother, wife, daughter, writer, activist, migrant, political awakening etc ( and not necessarily in the given order of importance). Fact is the moment you are aware of your personal histories the complexities of one’s ancestry become evident and it is no longer quite as simple to speak of genealogies in puritanical terms or of political action in black and white terms of “us and they”. Zainab Priya Dala is sharply articulate about these complex inheritances and is very aware of the fine negotiations it demands of her on a daily basis which is a given way of life. And it is precisely these day-to-day exercises in living that also sharply bring home to her details in society that Gandhi was blinded by. The South Africa in which he honed his political activism was primarily aimed at the racist modes of governance and not necessarily at recognising the microcosm of South African or South African Indian society and its distinct threads of identity. Curious that Gandhi who otherwise was so very sensitive missed these finer distinctions of identity especially since he and the author both have links to the Gujarati community. Yet for Gandhi it was apartheid of far more importance and it remained so till the 1990s when many of the South African social structures were realigned. In the new era it is not so much as race governing lines of social separation but money. With money becoming the defining factor of ancestries and communal make-up become even more acutely apparent. And as in the jungle, it is the survival of the fittest, same holds true for civil society. Those who survive in the new socio-economic terrain are also confident of their identity while aware of their historical, soci-political and genetic inheritances — a fact that Zainab Priya Dala is clear she will spell out for her children.

What Gandhi Didn’t See: Being Indian in South Africa is a sharp commentary on contemporary South Africa. It must be read. The thought-provoking essays will resonate with many readers especially women, across nations. Also for how smartly it puts the reader under the scanner and forces them to question and understand their inherited narratives better.

Read an extract from the book used with permission from the publishers — Speaking Tiger Books.

****

My father, a third generation non-resident Indian, whose grandfather had come from a village near Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh, preferred not to talk much about his heritage. But, things changed when he reached sixty years of age. Why? I will never know. But what I do know is that everything about my heritage from my paternal side had been spoken of by others, including my father’s brothers and sisters, not him. Maybe, he suffered the affliction of a love marriage to a woman who was seen as superior to him, and he wanted to delete his inferiority in the eyes of his children. But, I am seeing now how I also do the similar thing to my children. My husband, like my mother, comes from the big city of Durban, and his heritage is one of the Muslim business class that came to South Africa long after the indentured labourers** and anyway, let me just say it – he is considered higher class than I am, so we tend to appropriate this onto our children. Perhaps my father had done the same for many years. And, perhaps he decided to speak openly about our mixed up heritage only after my sister and I were safely and happily stowed away into good marriages. Things are sometimes as ugly as that. But speak he did. It became a river that never stopped. One day a year ago we were at a fancy dinner party held by my cousin from my mother’s side of the family – a very rich and successful doctor amongst a family of doctors. He lived in an area we still call today a White Area, which means that before 1994, none of us would have ever dreamed of walking past a house there, let alone living in one. My father was quiet during this dinner, but perhaps a few glasses of expensive whiskey loosened his tongue, and he started talking about his childhood on the farm. My mother tried to quieten him, not because she was ashamed, but because she knew he was about to cry. The room went silent as if a spell had been cast by a mournful farm-accented voice ringing out among the posh “white” accents of my cousins and his friends. But, minutes into his monologue, my cousin’s husband blurted:“Oh really now, Babs, should we get you an audition for another ‘Coolie Odyssey’?” (‘The Coolie Odyssey’ was a play on the indentured labourers written, directed by, and starring, Rajesh Gopie, a South African Indian dramatist).

My father fell into silence, and my husband, who is sensitive to the point of extreme protection of my father at most times, ushered him outside. I was carrying my baby son, and looking at these two men, standing next to a Balinese-inspired swimming pool, sharing a cigarette and probably chatting about the price of fuel, it was not lost on me that I was carrying in my arms the actual reality of a class divide. My son will always have to negotiate this divide and there is nothing I can do to protect him from it. Why would I need to protect him? Well, to put it as succinctly as I can, in South Africa, we let go of the caste system in the bowels of a ship in the 1800s, but we adopted a system that became very insidious. Fellow writers and historians, Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed in their detailed opus, Inside Indenture, A South African Story 1860 – 1914, describe these people who dropped their caste into the Indian Ocean as “twice-born.” Here, they refer to the fact that in the shiphold, there was no room for caste or class. An Indian inside there was an Indian who ate and slept alongside all others. But once they arrived at the port, and the documents of demographics were being created, a lower caste could easily take himself up a few notches. Today, in contemporary South Africa, caste is obsolete. We all know enough by now to question the Maharaja and Singh surname with a studied eye for actual refinement in behaviour, language and of course education. This does not mean there are no divisions. The divisions go deep. They are based on religion, economics, language and colour. Of course, I know that these divisions are changeable ones– much like dropping your caste at a shipyard, now you can change your religion, think and grow rich, lighten your skin and perfect your English. This malleability scares the ones who wielded class like gold crowns. I admit, my maternal family and my husband’s family are those that did. They are forgiven because they didn’t know they were doing it.

In South Africa, the business class came to the shores of Natal mainly from the villages of Gujarat. My father-in-law describes it well when he tells me in thick Gujarati: “One side of the street is Muslim Desai family. Opposite side of street is Hindu Desai family. Both Desais understand each other and get along better than even Muslim Urdu speakers or Calcuttiah people.”

I don’t look at anything he is saying as derogatory. The reason is that he is not insulting anyone, he is simply stating facts. The Gujarati community aggregated together in a code of business and called each other “Aapra-wallahs’. They still use this term today. An acquaintance, who is a great-grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, once came over to my house to collect items I wanted to donate to a family rendered homeless after a fire. I had known him for some years, and had interacted with him many times on charitable or literary correspondence. But, within minutes of the mutual spotting of an Aapra-wallah in the room, I ceased to exist in the conversation. My husband, a Muslim, and my associate, a Hindu, both spoke Gujarati that went far above my head. I had learned the basics of the language, to communicate with my husband’s family who spoke only Gujarati. My mother’s family were too high class to speak any vernacular, and only the Queen’s English would do. My father’s family spoke a combination of Urdu, Hindi and Bhojpuri. My best friend spoke Afrikaans and the children I grew up playing with spoke Zulu. Add to this mix the terms that each of us reserved for each grouping, which are as derogatory as being called Coolies, and it is no wonder that I cannot sleep some nights.

Indians who left as indentured labourers from the port of Calcutta are called Calcuttiahs, and Indians who left as indentured labourers from the port of Madras are called Madrasis. The Muslim community have their own lines of division and I find that these lines are deeply hurtful. Muslims who arrived in South Africa as indentured labourers are thought to come from Hyderabad. Although many chroniclers say that the majority of the Muslim community in South Africa who are not business arrivals are actually converts to Islam. This is how the Muslim community divide their people – colour and language. It used to be money, but now everyone is keeping up with the Joneses and the famous Gujarati Trust Funds** are running on empty, having cossetted very large and extravagant families for two generations.

The Memon Muslim community is a very small one, but they wield a large economic clout. They are known to have come from different areas around India, originally from Kathiawar, but finally settled as a community near Porbandar in Gujarat, from where a number of them migrated to South Africa as traders and businessmen. Another batch of Gujarati Muslims came from different villages in Gujarat, and left for South Africa from the port of Surat. They proudly refer to each other as Surtis and use the term “Hedroo,” to describe any other Muslim who is not Gujarati or Memoni. Hedroos, a terrible term, is used to speak of the class of Muslims whom the Surti community look upon as low class and poor. Inter-marriages between Surtis and Hedroos are still frowned upon. I am reminded of my own wedding day, when my husband’s aunt told me that in the history of the Dala family, it was the first time they had accepted a “mixed” girl for any of their boys. Their bloodline had remained pure Gujarati till 2006, the year of my nikkah. I responded to the aunt by a small nod that day, and replied to her: “Hahn ji.”

***

Footnotes

**Over 100,000 Indians arrived as slaves from the subcontinent in 1684 and lived in Cape Town. The first Indian indentured labourers arrived on 16 November 1860.The passenger/ trader Indians began arriving around 1875 to meet the need for commercial trade in the community, Black and Indian as well as Coloured.

**Gujarati Trust Funds were set up from the mid 1870s by wealthy Gujarati families, to cater for all educational, medical and housing needs of their community. When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, the Gandhi Trust was set up to cater for legal needs and to publish a newspaper called The Indian Opinion.

Zainab Priya Dala What Gandhi Didn’t See: Being Indian in South Africa Speaking Tiger, New Delhi, 2018. Hb. pp. 150. Rs 499

27 November 2018