Perumal Murugan “Pyre”

“…if we start this festival here with this impurity in our midst, we might incur the wrath of Goddess Mariyatha.”

…

Kumaresan, who had stayed quiet until then, suddenly lost his patience. ‘ I have married her,’ he snapped, barely concealing his irritation in his voice. ‘What is it that you want me to do now?’

…

‘Look here, Mapillai. Until we know which caste the girl is from, we are going to excommunicate your family. We won’t take donations for the temple from you, and you will not be welcome at the temple during the festival.’

( p. 132- 34)

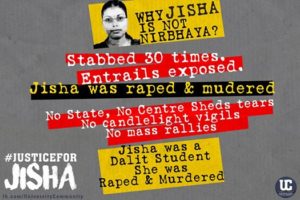

Award-winning writer Perumal Murugan shot to fame with his novel, One Part Woman, translated from Tamil into English. Unfortunately it was the sort of fame he could have done without since he was unnecessarily persecuted by lumpen elements that took offence at his novel. He was forced to publicly announce that he would no longer be writing. Yet there was one more novel – Pyre. A slim one revisiting his pet themes — male protagonists, social structures, caste, rituals and ordinary and believable people. Pyre is about Kumaresan who leaves his village in search of work where he falls in love and elopes to marry his beautiful neighbour. Alas this marriage is not welcomed in his village instead they are ostracised. Curiously enough Perumal Murugan never mentions the castes explicitly. There are enough indications in the book that the bride, Saroja, is a Dalit or the caste formerly referred to as “untouchables”. A sad practice that continues to be prevalent in India.

Pyre or Pookkuzhi was first published in Tamil by Kalachuvadu Publications. On my behalf Kannan Sundaram, publisher, Kalachuvadu asked Perumal Murugan if in the original text he had ever mentioned the castes. He confirmed he had never done it. The English translation by Aniruddhan Vasudevan by a brief introduction that dwells upon the novel being about caste and the resilient force it is, the unusual reliance of Perumal Murugan on direct speech, the difficulties of translating Tamil dialects used extensively in the story such as Kongu and Aniruddhan Vasudevan’s own habit as a translator to first draft a “very idiomatic translation”. But once again there are no references to this being a story involving a Dalit girl. So I posed a few questions to the translator.

- How true is the English translation of Pyre to the original Tamil? The English translation of ‘Pookkuzhi’ is very true to the original — nothing has been changed or consciously re-interpreted.

- How did you work on the translation? Only with the text or did you keep asking Perumal Murugan for assistance? I worked on the translation over several months. It took a lot of time mainly because my graduate school work grew more demanding. I did a first draft, in which I tried to keep the translation as close to the Tamil syntax as possible. So, necessarily, that would read quite a bit awkward in English. Perumal Murugan was, at the time of translating Pookkuzhi, caught in the middle of the tyranny whipped up around Madhorubagan. So I wanted to give him his space and approached Thoedore Bhaskaran for help with questions about Kongu Tamil. He was most kind. But at the later stage, I was able to consult Perumal Murugan.

- Did the author “tweak” the text for the English translation? In the Tamil edition does Murugan mention any of the castes? The English translation does not mention any but it is obvious that the caste angle is the basis of the anger in the story. PM didn’t tweak the text for English translation. ‘Pookkuzhi,’ in the Tamil original, does not have explicit caste names or place names. There are some recognizable markers and cues, but it does not take names. The caste angle gets foregrounded without explicitly naming castes. Through conversations, through references to people’s faith in caste hierarchy and practices, the novel manages to put caste and the difficulties of inter-caste marriage at the center.

- Is the “Tholur” mentioned in the novel in Kerala or Tamil Nadu? ‘Tholur’ mentioned in Pyre is, according to the plot of the novel, in Tamil Nadu. I don’t think it is an actual place, but a middle-sized town Perumal Murugan creates as a setting for Saroja and Kumaresan’s meeting and romance.

- Is Saroja a Dalit? Again, it is never explicitly mentioned, but the story itself and how she is perceived and treated point us in that direction.

- Why did you not include a more detailed introduction to the translation? I didn’t include a more detailed introduction, because I think there is an immediacy and accessibility to the narrative, and I didn’t want to stand in the way of it. I didn’t want to assume that the readers needed such a mediation besides the translation itself, which is, in itself, an act of mediation. I do hope I will soon be able to write about the process of translation itself and how it works for me. So far, despite the labour and the time involved, translating has been sort of a zen place for me.

Pyre is a novel that is not easy to provide a gist of except to say it is one of those books that will forever haunt one especially the dramatically chilling end. It is seminal reading. It is stories that like this that bring out the rich diversity of Indian literature.

Perumal Murugan Pyre ( Translated by Aniruddhan Vasudevan ) Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Books India 2016. Hb. pp. 200 Rs 399.

6 June 2016