( On Sunday, 7 January 2018, Asian Age published my article on the highlights of 2018. Unfortunately due to the constraints of space the sections on commercial fiction and children and young adult literature was dropped from the published article. So while I am reposting the original article, I have also included the sections that were dropped by highlighting the portions in red. )

( On Sunday, 7 January 2018, Asian Age published my article on the highlights of 2018. Unfortunately due to the constraints of space the sections on commercial fiction and children and young adult literature was dropped from the published article. So while I am reposting the original article, I have also included the sections that were dropped by highlighting the portions in red. )

The Indian book market, worth $6.76 billion, is perhaps one of the few where English language books sell well. As expected, 2018 is all set to sparkle — with new books and voices.

Among the prominent narrative non-fiction is the much-anticipated debut of Dreamers written by journalist Snigdha Poonam. It is a remarkable cultural study of the unlikeliest of fortune hawkers’ travels through the small towns of northern India to investigate the phenomenon that is India’s Generation Y. The other equally anticipated titles are Why I am a Hindu? by Shashi Tharoor; The Gujaratis: A Portrait of a Community by award-winning journalist Salil Tripathi; Him, Me, Muhammad Ali by Randa Jarrar, a collection of stories depicting the lives of Arab women, ranging from hypnotic fables to gritty realism; Legendary Maps from the Himalayan Club by mountaineer and Himalayan Journal editor, Harish Kapadia.

Devdutt Pattanaik’s The Book of Numbers: An Indian Perspective, about the significance of numbers in Indian culture, also delves into Vedic and Puranic connotations of each key number.

Some quirky titles to look forward to are Jadoo-wallahs, Jugglers and Djinns: A Magical History of India by John Zubrzycki which tells the extraordinary story of how Indian magic descended from the gods and came to be a part of daily rituals and popular entertainment. Also on the shelves this year will be Showtime: A Spectacular History of the Indian Circus by Anirban Ghosh, which tells the incredible story of the circus in India from the 19th century to the present.

It would be interesting, and topical, to read Past, Present and Future; Dissent, Despair, Dreams: Student Activism in India by Anirban Bandhopadhyay and Umar Khalid; Economics for Political Change: The Collected works of Manmohan Singh; Demonetisation and Black Money by C. Rammanohar Reddy.

Power by Barkha Dutt is about the twinned stories of the changing fortunes of the Congress Party and the rise of the BJP through the men and women who shaped events before 2014, and after.

Then there is Note by Note: The Great Indian Playlist by Seema Chishti, Sushant Singh and Ankur Bhardwaj that uses one song from each year, accompanied by a brief essay, and tells the story of India since 1947.

Two critical books on free speech include The Free Voice: On Democracy, Culture and the Nation by Ravish Kumar in which he examines while debate and dialogue have given way to hate and intolerance in India, how elected representatives, the media and other institutions are failing us, and looks at ways to repair the damage to our democracy; as will be Why India Needs a Free Press by N. Ram.

Biographies

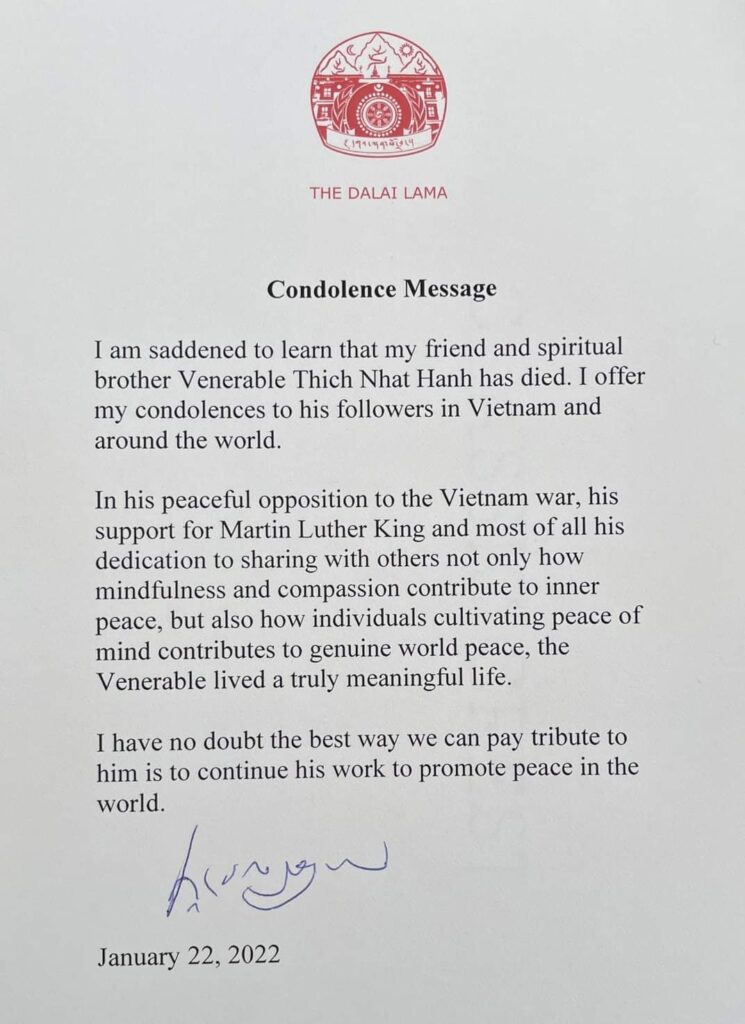

Some of the biographies/ memoirs to look forward to in 2018 are on film actors — Sanjay Dutt by Yaseer Usman, Sanjay Khan, Priyanka Chopra by Aseem Chhabra – and politicians. There’s veteran journalist Kuldip Nayar’s Close Encounters: The People I have Known and Biography of Mohan Bhagwat by Kingshuk Nag. The life stories of musicians Ilyaraja, Asha Bhonsle, S.D. Burman and Zakir Hussain (with Nasreen Munni Kabeer); spiritual leaders Dalai Lama (by Raghu Rai), Sri Sri Ravi Shankar (authorised biography, Gurudev, by his younger sister) and Shankaracharya (by Pavan Varma) and Amrita Sher-Gil will also be out this year.

Celebrity memoirs this year include actress Manisha Koirala’s cancer memoir and model-turned-health enthusiast Milind Soman’s book and Gauri Lankesh and the Age of Unreason by her close friend and former husband Chiddanand Rajghatta. Mentor by Hussain Zaidi about Dawood Ibrahim’s mentor, Khalid Pehelwan, who was instrumental in the formation and success of the D-gang are going to be the highlights of 2018.

Other notable books to look forward to are Nalini Jameela’s Romantic Encounters of a Sex Worker; Yashica Dutt’s Coming out as Dalit: A Memoir and The Idol Thief by S. Vijay Kumar, the shocking true story of one idol thief, Subhash Kapoor, behind the most outrageous thefts of Indian antiquities.

Literary memoirs not to be missed are Rosy Thomas’ memoir about her husband He, My Beloved CJ (translated from Malayalam by G. Arunima) and Na Bairi Na Koi Begana by crime fiction writer Surendra Mohan Pathak. It is the first in the three-volume autobiography of crime fiction writer Surender Mohan Pathak and chronicles his childhood in Lahore. The Hungrialists by Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury tells the remarkable story about how a generation of Bangla poets braved state censorship, loss of income and even imprisonment, and went on to transform literary culture in Bengal.

Fiction

Established writers too are coming up with their new books this year. These include Anita Nair’s Eating Wasps, Esther David’s Bombay Brides, Tabish Khair’s Night of Happiness, Rita Chowdhury’s Chinatown Days, Shandana Minhas’ Rafina, Anuradha Roy’s All the Lives We Never Lived, Mirza Waheed’s In His Hands, Amitabh Bagchi’s Half the Night Is Gone, Mahesh Rao’s Polite Society and Chandrahas Choudhury’s Clouds.

Travails with the Alien: The Film that Was Never Made and Other Adventures with Science Fiction by filmmaker Satyajit Ray brings together a collection of his many writings on the subject, including the script he wrote in the 1960s, based on a short story of his, for a science fiction film called The Alien. On being prompted by Arthur C. Clarke, who found the screenplay promising, Ray sent the script to an agent in Hollywood, who happened to represent Peter Sellers. Then started the “Ordeal of the Alien”, as some 20 years later, Ray watched Steven Spielberg’s film Close Encounters of the Third Kind and realised its bore and uncanny resemblance to his script The Alien, including the way the ET was designed! The book includes Ray’s detailed essay on the project with the full script of The Alien, as well as the original short story on which the screenplay was based, apart from some of his most celebrated writings on science fiction.

Commercial fiction writers like Nikita Singh, Yashodhara Lal, Trisha Das, Ravi Subramanian, Ira Trivedi and Sachin Bhatia, Ashwin Sanghi, Amish Tripathi, Durjoy Dutta, Ravinder Singh, Novoneel Chakraborty, Kevin Missal have books lined up in the new year. Also expected is the debut novel by Shweta Bachchan (Paradise Towers) and short stories by Shubha Mudgal.

Political narratives scheduled for 2018 include The Aadhar Effect by N.S. Ramnath and Charles Assisi; The RTI Story: The People’s Movement for Transparency by activist and main architect of Right to Information movement, Aruna Roy; AAP & Down: An Insider’s Account of India’s Most Controversial Party by Mayank Gandhi with Shrey Shah; and BJP: From Vajpayee to Modi by Saba Naqvi.

Equally fascinating should be Strongmen: Trump-Modi-Erdogan-Duterte, essays by Eve Ensler, Danish Husain, Burhan Sonmez and Ninotschka Rosca. An account of Kashmir by historian Radha Kumar and another one by former chief minister Omar Abdullah should be worth waiting for. At a time when “talaq” is being discussed, two timely books slated are by Salman Khurshid’s Three Times Unlucky and Ziya Us Salam’s Till Talaq Do Us Part.

Graphic novels

Graphic novels are steady sellers with a well-defined market too. Some of the titles anticipated are: Long Form Annual: The Best of Graphic Fiction & Non-Fiction edited by Sarabjit Sen, Debkumar Mitra, Sekhar Mukherjee and Pinaki De. It consists of stories about ordinary people, autobiographies, travel tales etc. As yet unnamed graphic novel about a teenager in America trying to come to terms with her Indian roots by new voice — Nidhi Chanani. Also to watch out for are First Hand 2: Graphic Nonfiction from India and Lotus and the Snake by Appupen.

Translations

Rich translation works worth a read include The Book of Mordechai and Lazarus: Two Novels by Gábor Schein (translated from the Hungarian by Adam Z. Levy and Ottilie Mulzet and Very Close to Pleasure, There Is a Sick Cat and Other Poems by Shakti Chattopadhyay (translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha). Some other notable titles slated in 2018 are: Chandni Begum: A Novel by Qurratulain Hyder (translated from the original Urdu by Saleem Kidwai); Tiger Women by Sirsho Bandhopadhyay (translated by Arunava Sinha) — it is the fictionalised story of Sushila Sundari, the first woman to perform in Indian circuses and gain immense popularity, Moisture Trapped in Stone: An Anthology of Modern Telugu Short Stories, translated by K. N. Rao; Timeless Tales from Bengal edited by Dipankar Roy and Saurav Dasthakur; Perumal Murugan’s double-sequel to One Part Woman; Jasmine Days by Benyamin.

Sahitya Akademi award-winning book If a River and Other Stories by Kula Saikia, currently DGP, Assam; On a River’s Bank by A. Madhavan (translated from Tamil by M. Vijayalakshmi); Here I am and Other Stories by P. Sathyavathi (translated from Telugu); Echoes of the Veena and other Stories by P. Sathyavathi (translated from Tamil); Havan by Mallikarjun Hiremath (translated from Kannada by S. Mohanraj) — this novel focusses on one of India’s most colourful wandering tribe, the Lambanis, who are found in large numbers in Karnataka and Maharashtra.

Some of the important women-centric publications of 2018 are: The Short Life and Tragic Death of Qandeel Baloch by Sanam Maher. The 25-year-old Qandeel Baloch who was Pakistan’s first celebrity-by-social media, shot to fame when she uploaded a video on Facebook mocking a presidential “warning” not to celebrate Valentine’s Day — a “Western” holiday. At the time, the Valentine’s Day video had been seen 830,000 times. Five months later, Qandeel Baloch would be dead. Her brother would strangle her in their family home, in what would be described as an “honour killing” — a murder to restore the respect and honour Qandeel’s behaviour online robbed him of.

Other titles are: Civilisations how do we look/ Eye of Faith by Mary Beard; Women Rulers of India by Archana Garodia; Tiger Women: Profile of Women Militants in India by Rashmi Saxena; Being “Her” in New India by Rana Ayyub; Like a Girl by Aparna Jain; Feminist Rani by Shaili Chopra and Meghna Pant; Daughters of the sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire by Ira Mukhoty; A Legal Handbook for Women by Nivedita Guhathakurta and Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan by Ruby Lal, a historical biography. The Bourbans and Begums of Bhopal: The Forgotten History by Indira Iyengar, a descendant of Jean Philippe de Bourbon, who arrived in India in the 1560s and was appointed a senior official by the Mughal Emperor Akbar, at his court in Delhi.

Children and young adult literature

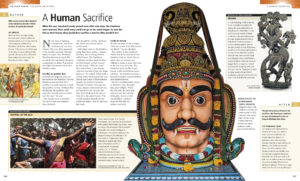

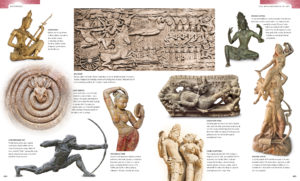

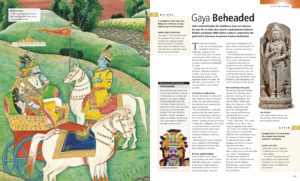

Children’s and young adult literature is a vibrant space with the healthiest growth rate. Some of the titles planned are a poetry and song collection by Gulzar; Vaishali Shroff on a journey of the Narmada to learn about the dinosaurs of India; a new Hill School Girls series by A. Coven; Timeless Biography series of HCI launches with Amrita Sher-Gil, a painter whose biography has also been released by Alka Pande for Tota Books. DK India has a phenomenal collection of heavily illustrated titles planned – The Ultimate Children’s Encyclopaedia, DK Indian Icons are their easy-to-use biographies, Birds about Delhi, 3D Printing, Robot. Indian myths for children by the brilliant storyteller Arshia Sattar; a delightful picture book The Cloud Eater by Chewang Dorji Bhutia and Prankenstein: The Book of Crazy Mischief edited by Ruskin Bond and Jerry Pinto. YA literature has some extraordinary titles such as The Other by Paro Anand; When Morning Comes by Arushi Raina in Duckbill’s ‘Not Our War’ series and is set in South Africa. It is about teenagers during the Soweto uprising of 1976. Why I Lie by Himanjali Sankar is a YA novel about mental health issues. Fireflies in the Dark by Shazaf Fatima , a young adult fantasy title that takes the reader deep into the world of jinns and shape changers and hidden family secrets. The Legend of the Wolf by Andaleeb Wajid , a fantasy horror novel for young adults.Refugee by Alan Grantz; The Lines We Cross by Randa Abdel Fattah and A very, Very Bad Thing by Jeffery Self.

2018 will sparkle with new books and voices!

7 January 2018