Guest post by Dipa Chaudhuri & Puneet Gupta, Co-translators of the Adventures of Asterix in Hindi

Astérix albums have been published in 111 languages and dialects, making it the best-selling comic book series worldwide, with 375 million copies sold to date. The series, popularly known as The Adventures of Asterix, was written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo and first appeared in the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Pilote, on 29 October 1959.

These

satirical comics focus on the adventures of the protagonists Asterix and

Obelix, and their village of Gauls, fending off Roman offensives in 50 BC, with

the help of a magic potion brewed by the venerable village druid, that

temporarily imparts the Gauls superhuman strength. Today, these adventures

have been adapted to animated and live action films, video games, theme parks,

and more. The first four albums—Gaulwasi Astérix (Asterix the Gaul);

Sone ki Darati (Asterix and the Golden Sickle); Astérix aur Gawthwasi (Asterix

and the Goths); Astérix Talwarbaz (Asterix the Gladiator)—are now available

in Hindi.

Ajay Mago,

Publisher, Om Books International, acquired the Hindi translation rights of The

Adventures of Asterix from Hachette Livres, France, after nearly 5 years of

negotiations that started in 2009 with a blind call at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

He just walked into the Hachette Livres stand, hoping to just walk out with the

Hindi rights for Asterix, a logical step after having recently acquired the

Hindi translation rights for The Adventures of Tintin from Editions Casterman.

Hachette

Livres wanted to see a detailed marketing plan for the books in Hindi. They

also insisted that the translation be carried out in Hindi from the

original comics in French and not from English. Given that I speak French

(I have an M.Phil. in French Literature from Université Paris Diderot-Paris 7)

and have been Chief Editor, Om Books International, since 2010, Ajay suggested,

I come on board. Thereafter, we got on board Puneet Gupta, an advertising

professional and a producer of audio visuals, who writes science fiction

novels, short stories and humorous poetry in Hindi. A die-hard comics

enthusiast since childhood, he has translated the comic series, Tintin, in

Hindi, also published by Om Books International. We then had to send Hachette

Livres a sample 10-page translation of Album 1 to prove our credentials. After

about a month, we received the stamp of approval—the translation was much

appreciated with a few changes here and there. Clearly, we were dealing with

publishers who needed to be convinced that they were interacting with a team of

professionals in India who would do right by the bestselling comic series in

the world. The rights were finally granted in 2014.

Given the

number of comics in the Asterix ‘canon’, and in the entire series, it was clear

that Ajay, Puneet and I were in it for the long haul. To begin with, Puneet and

I read up the entire series a few times to get the drift of the constants and

the variables. (At the moment, the first four albums are out. Completing

the series would take, at the very least, another couple of years.)

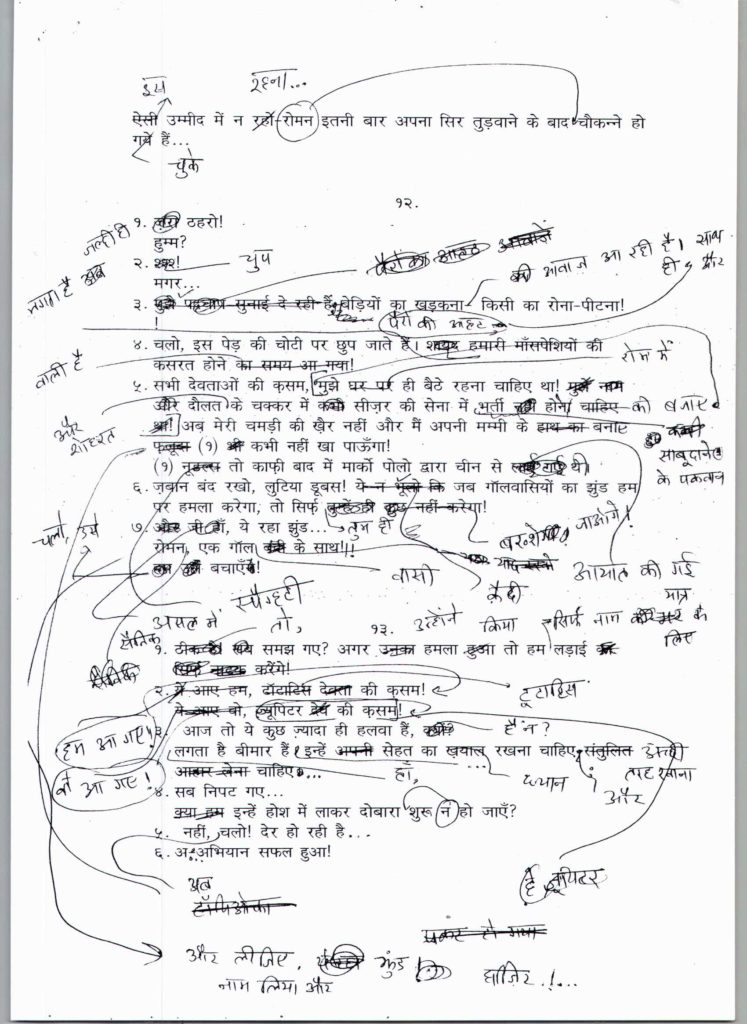

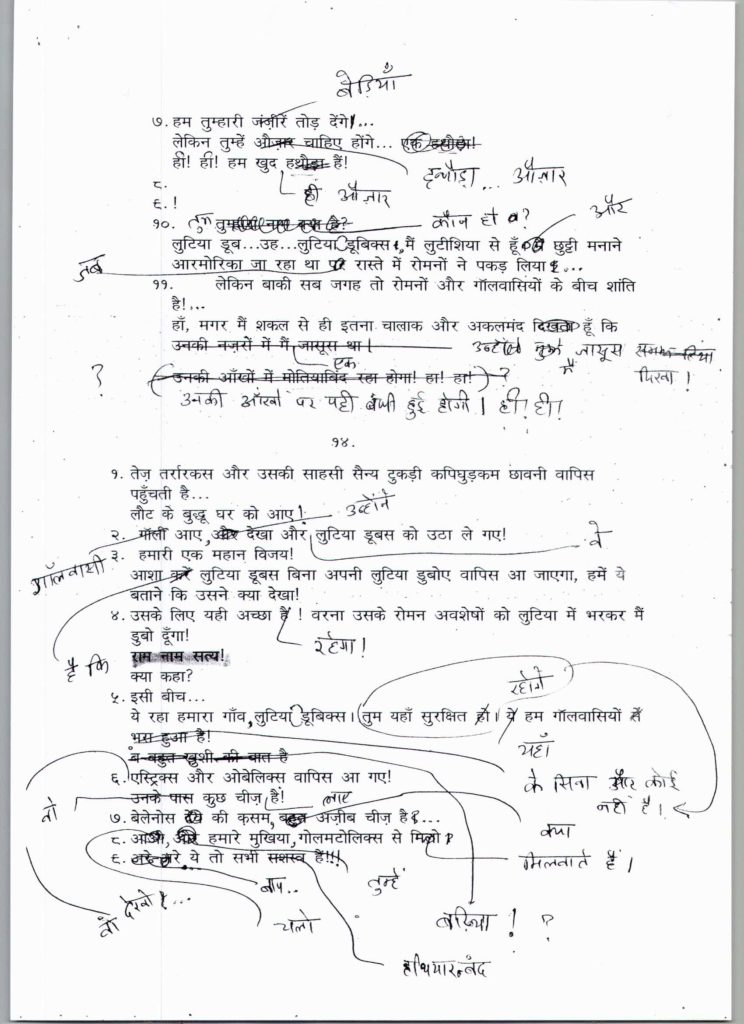

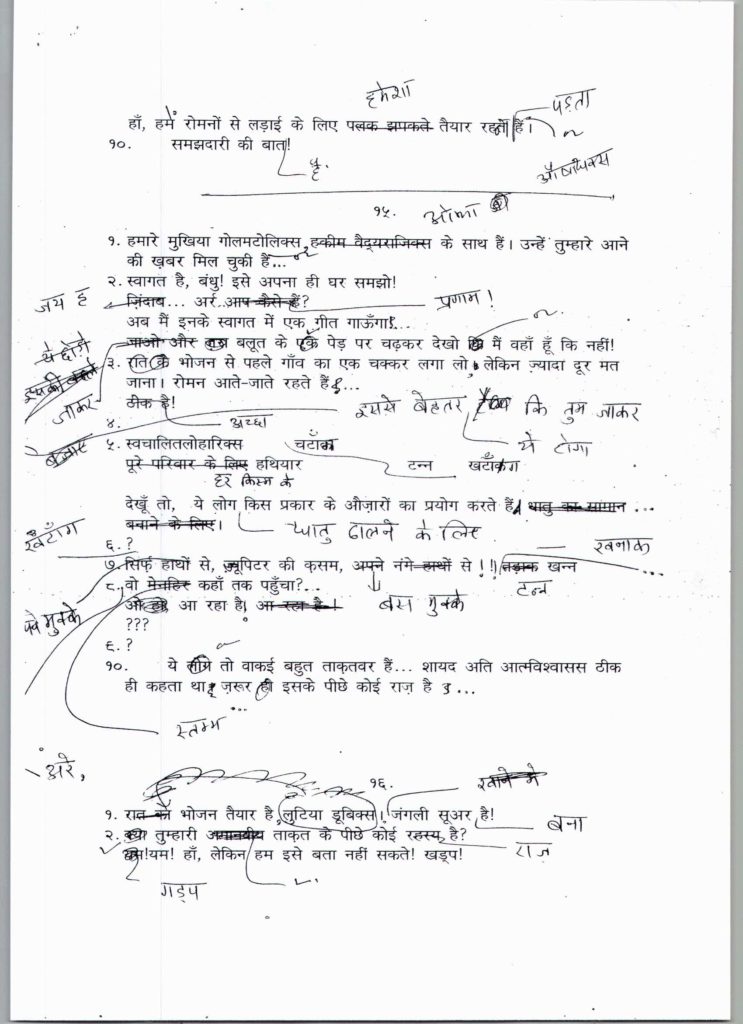

It was obvious that we were not dealing with a straightforward narrative and Puneet does not speak French. So I would share with him the multiple meanings of each dialogue/ frame, the wordplays and the etymology as also the distortions in the French originals. I would do that primarily in Hindi with the truly odd recourse to English. (it was a conscious decision taken by both of us to leave English out of the process). Thereafter, both of us would come up with multiple parallel possibilities in Hindi, till we got the context and register right each time. This is amply clear from the revisions on each draft (see scanned examples of handwritten revisions for Gaulwasi Asterix).

At the very

outset, we realised translating comics have practical constraints. The first

and immediate constraint is fitting the Hindi translation into each speech

bubble, despite Hindi being syntactically longer than French also because of

the maatras on the top, bottom and the side (in French, the accents are only on

the top and bottom).

While the

French comics are hand-written, we had to look for a similar font in Hindi that

could be typed out on the keyboard. At times, we needed to choose different

fonts that would establish the distinct accent with which a Goth would speak

for instance (in the English translation, the Gothic font was used for the

Goths). The font of the main copy was Kruti Dev 010. Kruti Dev 240 was used for

Goths in Asterix Aur Gauthwasi.

Besides the

fonts, we had to ensure that each linguistic community spoke with the accents

phonetically associated with it. So, the Goths took on harsh and guttural

sounds in Hindi. The accent was also a challenge when we were translating the

speech of a drunken sod. Besides slurred speech, words altered forms constantly

through a series of dialogue to indicate a constantly altered perception of

reality as is wont to happen when one is sloshed.

Apart from

Asterix and Obelix, the various gods and goddesses, and historical figure like

Julius Caesar, Vercingetorix, Cleopatra, whose names remain unchanged, renaming

the characters, designations, geographical coordinates was a challenging

exercise as each name in French and in Hindi has multiple meanings.

Each language

has a set of distinct sounds or onomatopoeia. We had to work our way through

the sounds from French to Hindi too, and already have a directory of over 150

onomatopoeia.

For pure

visual effect, more so after a vigorous exchange of fisticuffs, sounds in Hindi

had to be drawn and manually fitted into many frames without speech bubbles.

As we went along, it became clear that we were translating not only from French to Hindi, but depending on the provenance of the protagonist, we were translating from Latin, and on occasion, German too. This shall only get more complicated as Asterix and Obelix travel out to Britain, Egypt, Corsica, Spain, India, amongst other places, for the distorted nuances in French are likely to be borrowed heavily from the languages spoken in these places. So before translating the nuances into Hindi, we shall have to go into the etymology of the words, the idioms, the phraseology of the region in which the Asterix and Obelix find themselves. Negotiating

between different registers of each language to establish the social hierarchy

that binds the characters, was part of the task at hand.

The series is

replete with French songs, nursery rhymes, ditties, military marches etc. that

have often been distorted in the French version itself. That posed the twin

challenge of first decoding the original versions and then translating these

into Hindi with as many implicit and explicit layers of meanings carried

forward.

The comics

are also replete with intricate word play, sometimes running through a series

of dialogue, and on occasion, through several pages. As the word plays became

more complex, finding suitable translations became more challenging; we worked

through various options till we stumbled upon that epiphany, that elusive translation

which worked well.

Puneet Gupta

says “We had to decide on a few guidelines that would be followed in the course

of translating the entire series. These included the set of names of the

central characters, the Roman garrisons surrounding the village of the Gauls,

the various ethnic groups—the Romans, the Germans, the British or the

Egyptians, to name a few, all identified with a unique suffix as given to

them in the original text. Apart from historical figures such as Vercingetorix,

Julius Caesar, Brutus, Cleopatra, etc., all the other character names are puns

and mini jokes in themselves. In Sone ki Darati, there is a

shifty dealer Lentix, who we translated as Dal-me-kalix.

Barbaric

Germans tribes have funny sounding names, ending with a suffix “ic”—Teleferic,

Metric, Theoric, Periferic, Choleric and Histeric. According to their mental

make-up, we renamed them Atyacharik, Maardhadik, Becharik, Bimarik and

Mahamarik. The suffixes particular to linguistic and cultural communities were

retained as in the original.

We have also tried to retain the original flavour of many names. The dog, Idefix, or of fixed ideas, was renamed Adiyalix, someone who is doggedly obstinate, and loyal too.Druid Panoramix has become Ojha Aushadhiks. The village of the Gauls, is almost tribal in nature, and the druid is a combination of a medicine man and a witchdoctor, who brews potions with magical powers. Another character Cetautomatix, has been named Svachalit Loharix.

The military terminology was interesting too. Ranks such as Centurion and Decurion had to be suitably translated as well. So after much deliberation over the existing ranks in the Indian military, we took a cue from Senapati, and coined ranks like “Dashpati” for Decurion (a commander of 10 soldiers), and “Shatpati” for Centurion (commander of 100 soldiers) than settle for Major, Colonel etc. For every proverb, popular joke and clever turns of phrase in French, we hunted for a befitting equivalence in Hindi to ensure that the punch, wit and humour of the original were not lost in translation.”

Is the humour

in Asterix in consonance with the underpinnings on which the edifice of humour

per se reposes? Pretty much yes, so humour at its most irreverent, whether

anti-establishment or otherwise, feeds off cultural and ideological superiority,

racial, ethnic and linguistic slurs, gender stereo-typing and other devastating

premises that go beyond the pale of politically correctness. But most of us

play along since there is an unspoken pact between the

participants-interlocutors that it is all in jest and good cheer.

The

Adventures of Asterix is a comic series with a very significant graphic

element, the largely visual slapstick humour is conveyed efficiently through

the excellently drawn panels. Whether its our Gaul heroes settling scores with

an adversary, with only his teeth or sandals in the speech bubble to speak for

the devastating aftermath of the encounter, or the effect Besurtalix’s singing

has on everyone, a handful of translated sound effects in the panels

suffices to convey the drama and humour.

Literary

humour is rather difficult to translate. Fortunately, with the rich repository

of words, jokes, proverbs, songs, rhymes, poems, riddles and of popular lore in

Hindi, the search was usually crowned with sensible outcomes.

All through,

however, it was clear to us that we were not ‘converting’ the comics by

translating them into Hindi just as competent translations of the French,

Italian and Russian literary masterpieces into English or other languages were

meant to ‘communicate’ the narratives instead of ‘converting’ or ‘customising’

them to the cultural construct of the target language. Also, the imposing

visuals of Asterix would make it near impossible to ‘Indianise’ the comics. The

comics are being translated with the desire to share a cultural experience that

is quite unique, different, yet not dissimilar in the gamut of human

experiences.

This

translation project has been partly sponsored by the PAP Tagore Programme in

Paris and locally by the Institut Français en Inde. The idea of embarking

on a new narrative in each comic with its fresh round of challenges is

interesting for the simple reason that like all great classics, one is forever

discovering something new each time we look at a dialogue or frame, and for the

joy of decoding the wordplay, the cultural ciphers, and hopefully learning a

bit of the art by unravelling the code. We all would have picked up similar

linguistic and cultural subversions from the body of James Joyces’ works too.

What stays

with us is the great art of writing comics that are important alternative

histories that also deride such histories. Asterix is at the end of the day, a

great body of satire.

Indians being

polyglots, read in multiple languages. A considerable part of post-colonial

India and Indians have already been exposed to a plethora of world literature,

including comics and cartoons. We have grown up reading Superman, Phantom,

Mandrake, Modesty Blaise, Archie comics, Tintin and Asterix alongside Chacha

Chaudhry and Deewana (our home-grown version of good old Alfred E Neuman), RK

Laxman, Sudhir Dhar, Mario Miranda, and more. Our colonial heritage, now a part

of our socio-cultural DNA, is paradoxically a bane and a boon. We do not resist

either reading, writing or speaking in the language, supposedly, of the

‘others’ that over time has been embraced as a personalised mode of expression

by the ‘I’. There is already a huge readership of Asterix in English in India,

a country that has had a very strong tradition of comics not only in English

and Hindi, but in several regional languages as well. Asterix in Hindi is not

only for the strictly Hindiphone readers, but for comic buffs and collectors,

artists, ethnographers, translators, educational institutions across linguistic

boundaries, and across India and the world.

(C) Dipa Chaudhuri & Puneet Gupta

3 April 2019