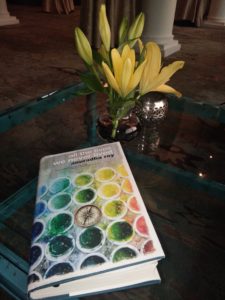

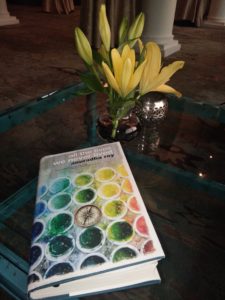

I read award-winning writer Anuradha Roy‘s stunning new novel All The Lives We Have Never Lived which is set during the second world war in British India and Bali. The narrator is Abhay Chand or Myshkin Chand Rozario who many years later in 1992 recounts details of his childhood. His mother was a Bengali Hindu and his father part-Anglo Indian. When Myshkin was nine his mother left the Rozario family. Myshkin was left in the care of his grandfather, a doctor, Bhavani Chand Rozario and his father, a college lecturer, Nek Chand. A couple of years after his wife’s departure Nek Chand left on a pilgrimage. He returned home with another wife, Lipi and a daughter, Ila.

I read award-winning writer Anuradha Roy‘s stunning new novel All The Lives We Have Never Lived which is set during the second world war in British India and Bali. The narrator is Abhay Chand or Myshkin Chand Rozario who many years later in 1992 recounts details of his childhood. His mother was a Bengali Hindu and his father part-Anglo Indian. When Myshkin was nine his mother left the Rozario family. Myshkin was left in the care of his grandfather, a doctor, Bhavani Chand Rozario and his father, a college lecturer, Nek Chand. A couple of years after his wife’s departure Nek Chand left on a pilgrimage. He returned home with another wife, Lipi and a daughter, Ila.

Gayatri Sen left India for Bali with German artist Walter Spies and another friend of his Beryl. While in Bali, Gayatri would write letters to her son but particularly long and detailed ones to her best friend Lisa McNally. Myshkin receives his mother’s correspondence to Lisa from her children upon her death.

After finishing the novel I wrote Anuradha Roy a long letter. Here are some excerpts.

*********

Dear Anuradha,

Today I finished reading All the Lives We Never Lived. It is another one of your stories that will be with me for a long, long time to come.

long, long time to come.

I loved the dramatic opening sentence “In my childhood, I was known as the boy whose mother had run off with an Englishman.” It is similar to another novelist I thoroughly enjoy — Nell Zink. I like how you begin as from the present moment, with the boy, now an old man, reflecting back to his childhood. Obviously the opening sentence defined him for years as that is what is crystal clear. He echoes what society says about his mother. Although the rhythm and cadences of the text are so correctly measured with never a word out of place. It is a voice of experience speaking, yet one who is so terribly (and understandably) rattled by his mother’s letters towards the end that he walks through the local marketplace distractedly.

Your descriptions of the women writing letters to each other with every line scrawled upon, as well as in the margins and wherever they could find space transported me back immediately to my days of writing letters. When my friends left India, I would send them letters by snail mail. In those days’ international postage was so expensive for the heavy packets since the letters were long and used a lot of paper. So I devised a method of using an aerogramme and writing as tiny as I could and then writing across the margin and filling up whatever little space I could find on the page.

So you can imagine my delight to discover the letters between Gayatri and Lisa McNally in All the Lives We Never Lived. You had to my mind so effectively managed to make that leap of unearthing memories not only of the characters but also of the reader. So many times I found myself slowing down or grinding to a halt in your descriptions of the plants and trees. The descriptions of the gardener plucking the jasmine and collecting them in a basket of white cloud to later thread them as a gajra for Gayatri brought back a flood of memories. Every morning in the searing summer heat I would go to my grandmother’s garden in Meerut and pluck all the beautiful white blooms off the bushes. Later I would thread the flowers into gajras for the women in the family. It was a daily ritual over summer vacation I loved. The moment I read that passage in your book I got a strong whiff of the sweet fragrance of the flowers –perfect for summer as well as of the needle used to thread would be coated with sticky nectar.

The beauty of nature, the flowering trees whether in the scorching dry heat or in the tropics to the mountain vegetation. The burst of colour in your novel makes its presence felt but what is truly exhilarating is how Gayatri and later her son gets associated with the most vibrantly colourful passages describing nature in the book. The passage where you describe Myshkin filling up his long-unused sketchbooks with studies of trees and plants in the garden while remembering his mother are like the last movement of a symphony, where everything comes together as a whole. It is as if Myshkin is expressing his delight at discovering the joy of who his mother was and experiencing her life through his paintings.

Over the next weeks, my long-unused sketchbooks filled with studies of the trees and plants in the garden that I associated with my mother: the pearly carpet of parijat flowers, Nyctanthes arbortristis, that she loved walking on barefoot; the neem near the bench where she had sat with Beryl listening to the story of Aisha. I barely slept, I forgot meals, I drew and painted her garden as if possessed. I drew the Crepe myrtle and Queen of the Night, the common oleander and hibiscus; the young mangoes on the tree in June, as raw as they had been when Beryl de Zoete and Walter Spies first came to our house.

It took me five days to finish my studies of Queen of the Night and then I turned to the garnet blossoms of the Plumeria rubra, the champa. I painted the long, elliptic leaves, the swollen stem tips, the fleshy branches that go from grey to green and ooze milk if bruised or cut. I blended in the ochre at the edges of the petals with the deepening incandescence of the red in the depths of the flower.

Your descriptions of the gulmohar and amaltas trees (though you use the scientific names) are stupendous. One has to live in this ghastly dry heat of the north Indian plans to realise just how much the bright deep rich yellows and fiery reds actually seem pleasant on a hot summer day. Of course the entire sub-plot of the Sundar Nursery and the superintendent of horticulture, Alick Percy-Lancaster, is absolutely fascinating! Years ago I recall you had published the gardening journals of the nursery in a brown hardback with a dustjacket. It is still one of my prized possessions. So I absolutely understood your love for greenery and making a new city green, or the distress at the unnecessary felling of the neem trees in Calcutta and Myshkin’s grief for it was he who had planted the saplings as a young horticulturist.

The characters you create are always so memorable. In a very male household there are only two women – the ayah/cook Banno Didi and Gayatri—who “typically” do not have much of a say in what is happening but the authorial eye gives sufficient clues to the existence of the women and it is not just the tantrums they throw. Or even the religious leader Mukti Devi, head of the Muntazi Seva Gahar, Society for Indian Patriots, whose image in the reader’s mind is created by Nek Chand’s accounts of her. Later even Myshkin’s surprise and then cruel assertion with his stepmother to lord it over in the manner he has seen his father behave, brings into play the sense of patriarchal entitlement men seem to have – even the best of them. This is exactly why I was so surprised to read the exchange of letters, of which only one set remain, but that is enough to give a great insight into the free spirit Gayatari was. There are so many women in this novel, some prominent (Gayatri, Lisa, Lipi, Banno, Beryl), some absolutely silent (Kadambri, Queen Fatima and Lucille) and others with walk-on parts (Ila’s daughter, Gayatri’s mum, Ni Wayan Arini and many of those in Indonesia). The little interlude with the story of Amrita from Maitreyi Devi’s novel is fantastic too.

The first half of the book is full of men but in the second half the women take over the narrative. You suddenly make visible that is mostly invisible to most eyes, especially male eyes, of the myriad ways in which women manage the daily rhythms of life. It is not just the concerns Gayatri has for her family and mentions it often to Lisa but also the management of it long distance by persuading Lisa to keep a kindly eye on the grandfather and Myshkin. And yet, it is very liberating to see how you make visible the thoughts of the women, their innermost thoughts, their experiences that are usually never made public. Lipi is the only one who upset at her husband’s high-handedness of sending her home instead of allowing her to sit through the musical concert because of her toddler Ila prompts Lipi to create a massive bonfire. She is very direct in her response; almost earthy.

You weave these intricate webs but ever so slightly shift perspectives too. Little Myshkin observes everything, perhaps not always quite understanding it, and yet he absorbs. It becomes a part of who he is and it is best expressed in his writing and later the paintings he draws as an old man. What I truly loved about the novel was how at the beginning the women and men were operating as expected in their socially defined gendered roles despite the magnificent opening line. The prose moves as one would want of a well-structured novel. It lulls one into expecting a good old fashioned story with a few unpredictable twists. Then come the disruptions not just to the domestic setup but also to the prose, the letters make their presence felt and force the reader to engage with the female mind set, even the “common or garden species of readers” is forced to be involved! You reserve many of the tiny details that really evoke the period in the women’s correspondence; later this fine eye for the “thingyness of things” is visible when old Myshkin begins to paint with as much care and attention to detail as his mother may have done.

At another level I felt that Gayatri was trapped yet the manner in which she comes free and you express it so well by changing the text form too. From the “rigidity” of long prose — since it does have a bunch of rules governing it — to the free flowing style of letters. It is not just the breaking of shackles of the form to express herself to Lisa but also the manner in which Gayatri writes. There is a sense of freedom. The correspondence is so much like the intimate conversations women have with each other, whether strangers or friends. They immediately lapse into it.

For someone so one with the elements as Gayatri seems to have been it is does not seem to be out of order to have her engulfed in so many charming stories beginning with Beryl’s own life or her narration of man-woman Aisha, or even Walter Spies himself. The freedom with which they lived; possibly Bohemian but undeniably a very talented group of individuals. Everyone had tremendous “backstories”, some dastardly, all possibly true, and yet their zest for life to explore more and more was so in keeping with character. Through these experiences she meets or hears about different forms of sexualities that exist; Gayatri accepts all these stories and never judges, instead wonders “There must have been a time when love did not have moral guardians saying you may do this but not that – this is how it is in Bali now & how it was in our country hundreds of years ago”.

The parallels that you draw tell another narrative too. For example, referring to Gayatri as “The Indian Painter” and recounting the Amrita story in Maitreyi Devi’s novel is so deftly done as if to silence critics who may be prompted to say that feisty, independent, strong-willed, headstrong women like Gayatri who is “glad to have time to work” could not possibly have existed in British India. The political-historical parallels are unmistakable as well with Arjun’s desire for the country to be governed by a “benign dictatorship” followed by Nek Chand sighing about his students who were locked up for sedition “We are fugitives in our own land.” Gayatri’s statement “I am finding out how limited my world was” seems to resonate at many levels for this story and modern India. Gayatri is ever so magical in the manner in which you create her. She comes across as a modern woman but caught in the wrong time. Sadly though how many women living today can still express themselves or be so confident as to take charge of their own lives as Gayatri did?

The title of the book + the epigraph taken from Tobias Wolff “This is a book of memory, and memory has its own story to tell”, only coalesce as significant once the book is finished. I loved the way in which you immerse the reader as if to exist within a Greek chorus, a multitude of voices, giving their often unasked-for opinions, and yet doing a fantastic job of recreating a moment or a “truth” within a community. The vagueness of the town adds to the blurriness of incidents happening in the past. I do not know how to explain it to say that the story exists in the past sufficiently and in the memory of Myshkin to be real and yet, a little hazy. Loss of the finer details are immaterial as long as the period is evoked; and even the importance of that fades away as the story progresses. And yet reading my response to your book I realise this story will trigger many memories for many readers for you tease out the floodgates of memory ever so gently and politely. It worked for me. It is a powerful book.

Yours,

JAYA

Anuradha Roy All The Lives We Never Lived Hachette India, Gurugram, India, 2018. Hb. pp. 334. Rs 599

27 May 2018