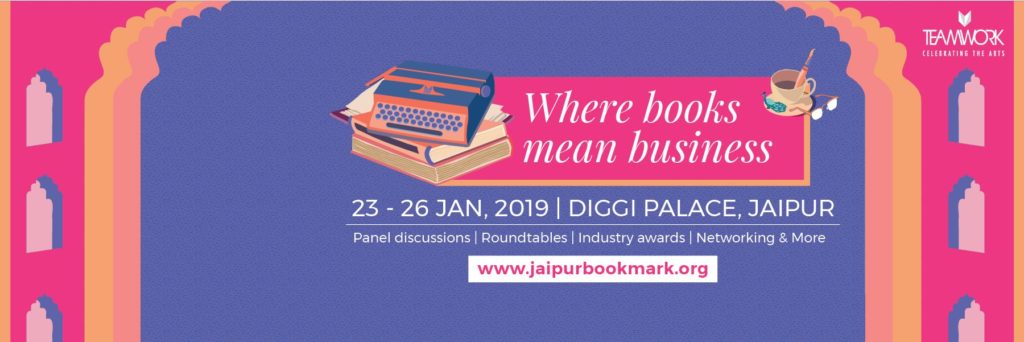

Juergen Boos, President/CEO, Frankfurt Book Fair/ Frankfurter Buchmesse, on “Freedom to Publish”, 23 Jan 2019, Jaipur Bookmark

Juergen Boos, President/CEO, Frankfurt Book Fair/ Frankfurter Buchmesse, delivered the inaugural speech at the Jaipur Bookmark. It is the business conclave that is inaugurated the day before Jaipur Literature Festival and then runs parallel with the litfest. It is an exciting B2B space for publishing professionals to network. Juergen Boos’s speech is published here with his kind permission.

******

Dear Namita Gokhale,

Dear William Dalrymple,

Dear Sanjoy K. Roy,

Dear Colleagues and Friends,

Thank you very much for the invitation to speak here today. The Jaipur Literature Festival is a festival of cultures, language, ideas and literature, and I feel very privileged to have the chance over the next few days to listen to so many Indian authors and personalities from around the world and to converse with them.

At this confluence of cultures, I’m pleased to address the friends from the trade at Jaipur Bookmark today.

After all, that is the fundamental principle of any literature festival: creating an environment for interactions that promote the free exchange of ideas and opinions.

The free exchange of ideas and opinions – never has that been easier than today, in the 21st century.

And never has it been so threatened.

Over the past 20 years, communications technology has taken an evolutionary leap, one that surpasses anything the most far-sighted science-fiction writers of the 19th and 20th centuries could have imagined.

In Stanley Kubrick’s film “2001: A Space Odyssey” from the year 1968, Dr Heywood Floyd, an astronaut, has a “videophone call” with his daughter while at the space station.

Fifty years later, in the summer of 2018, the German astronaut Alexander Gerst used his mobile phone to take fascinating photos of his time at the International Space Station, images which were transmitted around the world.

Videophones, computer tablets, artificial intelligence, voice control – many of the things that Kubrick envisaged 50 years ago have become reality.

According to the 2018 Global Digital Report,[1] of the four billion people around the world who have access to the Internet, more than three billion use social media every month. Nine out of ten users log on to their chosen platforms using mobile devices.

The number of people who use the most popular platforms in their respective country has grown over the last 12 months by almost one million new users each day.

What I find remarkable here is that not only has communications technology made a quantum leap, the devices that allow the world’s population to participate in the global conversation have also become so inexpensive that almost everyone can afford one.

That is giving rise to a previously unknown participatory process, one that has the power to change democracy’s traditional ground rules:

Everyone today is in a position to publish whatever they want – using blogs, podcasts and self-publishing platforms, as well as traditional publishing houses. News is transmitted around the globe in the fraction of a second, and social networks allow us to reach more readers and viewers than ever before.

In just a minute I will talk about the challenges and consequences that are resulting for the publishing industry.

First, however, let’s look at the darker side of these developments:

In the 21st century, a few select businesses have become private superpowers. They can do more than most countries to promote or prevent a free exchange of opinions.

Via social networks, phenomena like the viral spread of fake news, hate speech and slander now have a global impact.

Professional trolls strategically destabilise political discourse online, fuelling populist, nationalist and anti-democratic tendencies throughout Europe and around the globe.

One observes that, here in India, free speech is facing a threat sprouting from religious motivations, political biases and social judgments. Attempts in the recent past to silence journalists, writers, film-makers and publishers reflect the rise of identity politics and apathy on the part of the state. Two journalists of international repute – Gauri Lankesh and Shujaat Bukhari – were shot dead within a span of nine months. Publisher friends like DC Books, Kalachuvadu Publications and their authors have witnessed attacks by fanatics who may have never even read the books in question.

When I look at the hysteria, hatred and hostility that characterise the discussion in social media, the permanent state of turmoil that societies around the world find themselves in, then I begin to doubt whether we are actually capable of using the communications technologies whose development we are so proud of.

To paraphrase Goethe: “The spirits I called / I now cannot rule”.

In social media, language is used as a destructive weapon day in and day out, and it’s become clear how disastrous this can be for those individuals targeted by the bullying. It can even lead to murder.

In his 2016 book Free Speech, which you undoubtedly know, the British historian Timothy Garton Ash examines the question of how free speech should take place.

He asks which social, journalistic, educational, artistic and other possibilities can be realised to ensure that free speech proves beneficial by facilitating creative provocation without destroying lives and dividing societies.[2]

He comes to the conclusion that the less we want to have laid out by law, the more we have to do ourselves.

After all, Ash explains, there is no law that can draw a line between freedom and anarchy – every individual must look within before expressing himself or herself and must take responsible decisions.

I would like to talk with you about this “how” in the coming days and hear your opinions.

Personally, I feel that the participatory process I mentioned before requires us – our industry, but also each of us as individuals – to take a stance. Expressing an opinion of this type was long reserved for politicians or the media. Today, in the 21st century, we all have the possibility of making our voices heard.

And we should not do that in keeping with the motto “overnewsed but uninformed,” but in a carefully considered manner.

I believe that this permanent state of turmoil is troubling, this hysteria which does not stop at speech, but which now increasingly leads to violence.

Personally, I’m alarmed at how the language we use is becoming increasingly coarse and, following from that, the way we interact with each other.

The problem about this state of turmoil is that it usually results in the exclusion of others and, consequently, causes even deeper trenches to be dug.

Yet how can we deal with the challenges of our time – and find solutions to them – if not in dialogue with each other?

That leads to the question: what responsibility do publishers bear, does our industry bear, today, in the post-Gutenberg era?

How can publishing houses and their products remain relevant in an age in which fake news can be disseminated faster than well-researched books?

In which rumours, supposition and conjecture are more quickly viewed, liked and shared than texts capable of explaining complex contexts?

As my friends Kristenn Einarsson and José Borghino have pointed out on many occasions, “If we are to create and maintain free, healthy societies, then publishers must have the will and the ability to challenge established thinking, preserve the history of our cultures, and make room for new knowledge, critical opposition and challenging artistic expression”.[3]

Publishers in the 21st century are in a privileged position: the industry looks back on a long tradition, on the one hand, and has built a reputation. Publishers are gatekeepers – they filter and assess content, they curate before they publish.

They consider it part of their job to publish content that is well-researched, documented, checked and carefully assembled as way of contributing to the range of opinions present in society.

On the other hand, they now have the possibility of reaching their readers through various channels, offering their expertise, their content and their opinion exactly where their target group is found.

Publishers and authors in many parts of the world risk their lives by writing or bringing out books that criticise regimes, uncover injustices and shed light on political failures.

On 15 November 2018, the Day of the Imprisoned Writer, Arundhati Roy wrote the following in a letter to the Bangladeshi writer, photographer and human rights activist Shahidul Alam: “How your work, your photographs and your words, has, over decades, inscribed a vivid map of humankind in our part of the world – its pain, its joy, its violence, its sorrow and desolation, its stupidity, its cruelty, its sheer, crazy complicatedness – onto our consciousness. Your work is lit up, made luminous, as much by love as it is by a probing, questioning anger born of witnessing at first hand the things that you have witnessed. Those who have imprisoned you have not remotely understood what it is that you do. We can only hope, for their sake, that someday they will.”[4]

As you know, Shahidul Alam was taken into custody in July of last year after he criticised the government of Bangladesh in an interview with Al Jazeera and in various Facebook posts.[5] Fortunately he has since been freed, but the charges against him remain.

Without wanting to turn these very personal remarks by Arundhati Roy into a generalisation, I would just like to say that she has put it in a nutshell when she writes that, through their work, writers, authors, journalists and artists draw a vivid map of humankind in our part of the world.

Journalists and other authors write despite intimidation and threats. Like Shahidul Alam, they are driven by a mixture of love and anger. For that, they deserve our highest esteem and respect.

Writers and journalists are being intimidated and forced into silence all around the world because of their political and social engagement, something we condemn in the strongest possible terms.

As discoverers and disseminators of ideas and free thought, we, as a community, have a greater responsibility to uphold freedom of expression. At the same time, we cannot withhold our criticism of its misuse.

I hope to have the chance to speak with many of you about these issues in the coming days.

Thank you.

[1] https://wearesocial.com/de/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018

[2] (Kapitel Ideale, Seite 123)

[3] Zitiert in Nitasha Devasar: Publishers on Publishing – Inside India’s Book Business

[4] https://pen-international.org/news/arundhati-roy-writes-to-shahidul-alam-day-of-the-imprisoned-writer-2018

[5] https://pen-international.org/news/shahidul-alam-writes-to-arundhati-roy

13 February 2019