Jaya’s newsletter 8 ( 14 Feb 2017)

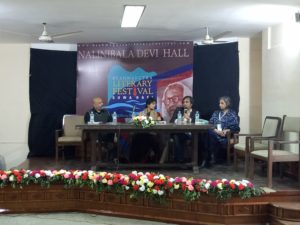

It has been a hectic few weeks as January is peak season for book-related activities such as the immensely successful world book fair held in New Delhi, literary festivals and book launches. The National Book Trust launched what promises to be a great platform — Brahmaputra Literary Festival, Guwahati. An important announcements was by Jacks Thomas, Director, London Book Fair wherein she announced a spotlight on India at the fair, March 2017. In fact, the Bookaroo Trust – Festival of Children’s Literature (India) has been nominated in the category of The Literary Festival Award of International Excellence Awards 2017. (It is an incredible list with fantabulous publishing professionals such as Marcia Lynx Qualey for her blog, Arablit; Anna Soler-Pontas for her literary agency and many, many more!) Meanwhile in publishing news from India, Durga Raghunath, co-founder and CEO, Juggernaut Books has quit within months of the launch of the phone book app.

It has been a hectic few weeks as January is peak season for book-related activities such as the immensely successful world book fair held in New Delhi, literary festivals and book launches. The National Book Trust launched what promises to be a great platform — Brahmaputra Literary Festival, Guwahati. An important announcements was by Jacks Thomas, Director, London Book Fair wherein she announced a spotlight on India at the fair, March 2017. In fact, the Bookaroo Trust – Festival of Children’s Literature (India) has been nominated in the category of The Literary Festival Award of International Excellence Awards 2017. (It is an incredible list with fantabulous publishing professionals such as Marcia Lynx Qualey for her blog, Arablit; Anna Soler-Pontas for her literary agency and many, many more!) Meanwhile in publishing news from India, Durga Raghunath, co-founder and CEO, Juggernaut Books has quit within months of the launch of the phone book app.

In other exciting news new Dead Sea Scrolls caves have been discovered; in an antiquarian heist books worth more than £2 m have been stolen; incredible foresight State Library of Western Australia has acquired the complete set of research documents preliminary sketches and 17 original artworks from Frane Lessac’s Simpson and his Donkey, Uruena, a small town in Spain that has a bookstore for every 16 people and community libraries are thriving in India!

Some of the notable literary prize announcements made were the longlist for the 2017 International Dylan Thomas Prize, the longlist for the richest short story prize by The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award and the highest Moroccan cultural award has been given to Chinese novelist, Liu Zhenyun.

Since it has been a few weeks since the last newsletter the links have piled up. Here goes:

- 2017 Reading Order, Asian Age

- There’s a pair of bills that aim to create a copyright small claims court in the U.S. Here’s a breakdown of one

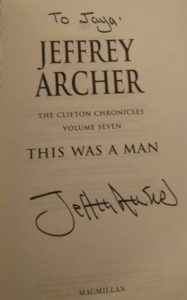

- Lord Jeffery Archer on his Clifton Chronicles

- An interview with award-winning Indonesian writer Eka Kurniawan

- Pakistani Author Bilal Tanweer on his recent translation of the classic Love in Chakiwara

- Book review of Kohinoor by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand

- An article on the award-winning book Eye Spy: On Indian Modern Art

- Michael Bhaskar, co-founder, Canelo, on the power of Curation

- Faber CEO speaks out after winning indie trade publisher of the year

- Scott Esposito’s tribute to John Berger in LitHub

- An interview with Charlie Redmayne, Harper Collins CEO

- Obituary by Rakhshanda Jalil for Salma Siddiqui, the Last of the Bombay Progressive Writers.

- Wonderful article by Mary Beard on “The public voice of women”

- Enter the madcap fictional world of Lithuanian illustrator Egle Zvirblyte

- Salil Tripathi on “Illuminating evening with Prabodh Parikh at Farbas Gujarati Sabha”

- The World Is Never Just Politics: A Conversation with Javier Marías

- George Szirtes on “Translation – and migration – is the lifeblood of culture”

- Syrian writer Nadine Kaadan on welcoming refugees and diverse books

- Zhou Youguang, Who Made Writing Chinese as Simple as ABC, Dies at 111

- Legendary manga creator Jiro Taniguchi dies

- Pakistani fire fighter Mohammed Ayub has been quietly working in his spare time to give children from Islamabad’s slums an education and a better chance at life.

- #booktofilm

- Lion the memoir written by Saroo Brierley has been nominated for six Oscars. I met Saroo Brierley at the Australian High Commission on 3 February 2017.

- Rachel Weisz to play real-life gender-fluid Victorian doctor based on Rachel Holmes book

- Robert Redford and Jane Fonda to star in Netflix’s adaptation of Kent Haruf’s incredibly magnificent book Our Souls at Night

- Saikat Majumdar says “Exciting news for 2017! #TheFirebird, due out in paperback this February, will be made into a film by #BedabrataPain, the National Award winning director of Chittagong, starring #ManojBajpayee and #NawazuddinSiddiqi. As the writing of the screenplay gets underway, we debate the ideal language for the film. Hindi, Bengali, English? A mix? Dubbed? Voice over?

- 7-hour audio book that feels like a movie: Julianne Moore, Ben Stiller and 166 Other People Will Narrate George Saunders’ New Book – Lincoln in the Bardo.

- Doctor Strange director Scott Derrickson on creating those jaw-dropping visual effects

- Lion the memoir written by Saroo Brierley has been nominated for six Oscars. I met Saroo Brierley at the Australian High Commission on 3 February 2017.

New Arrivals ( Personal and review copies acquired)

- Jerry Pinto Murder in Mahim

- Guru T. Ladakhi Monk on a Hill

- Bhaswati Bhattacharya Much Ado over Coffee: Indian Coffee House Then and Now

- George Saunders Lincoln in the Bardo

- Katie Hickman The House at Bishopsgate

- Joanna Cannon The Trouble with Goats and Sheep

- Herman Koch Dear Mr M

- Sudha Menon She, Diva or She-Devil: The Smart Career Woman’s Survival Guide

- Zuni Chopra The House that Spoke

- Neelima Dalmia Adhar The Secret Diary of Kasturba

- Haroon Khalid Walking with Nanak

- Manobi Bandhopadhyay A Gift of Goddess Lakshmi: A Candid Biography of India’s First Transgender Principal

- Ira Mukhopadhyay Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth & History

- Sumana Roy How I Became A Tree

- Invisible Libraries

14 February 2017