“Sight” by Jessie Greengrass

…the framing of a radical scientific discovery in ordinary language, the ability to impart understanding without first having to construct a language in which to do so. Rontgen’s description of his work comes like the unravelling of a magician’s illusion which, explained quickens rather than diminishing, the understanding of its working conferring the illusion of complicity …

Jessie Greengrass’s debut novel Sight is about an unnamed narrator pondering whether to have a child or not.

I wanted a child fiercely but couldn’t imagine myself pregnant, or a mother, seeing only how I was now or how I thought I was: singular, centreless, afraid.

It is a long reflection by the narrator split into three parts like a play with a short interlude. Every section itself is structured with the long self-reflecting passages about by the narrator interspersed with interludes with factual historical content. The first section involves the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, and Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays; the second section is about psycho analyst Sigmud Freud and the final section is about Scottish surgeon John Hunter who was exceptionally well known for his knowledge of the anatomy, both human and animal. In fact John Hunter’s fine collection of over 14,000 specimens was acquired by the British government and even today exists at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Interestingly every section while the narrator reflects it corresponds with a particular moment in her life. The first section while she tussles whether to get pregnant or not she also contemplates upon Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays whose experiments in the laboratory resulted in a big impact on medical science and society too. It was the intensely subjective moment that led to greater objectivity:

For seven weeks and three days Röntgen existed in a private world transformed for him and him alone, and perhaps this too was a part of his later bitterness: that despite this experience of revelation, the conferral on him of a scientific grace, afterward nothing was different at all, and although he had seen through metal and seen through flesh to what was hidden, and although he had known, or thought that he had known, its nature, what had been left afterwards was only so much quibbling on the bill.

Similarly mothering her firstborn, remembering the death of her mother due to cancer while the narrator herself was in her early twenties leaving her an orphan, sharing her fears with her partner Johannes whether to have the second baby or not, while wondering if she is capable of the responsibility — these are intensely personal experiences for any woman more so for the narrator. Pregnancy is a very female experience that is repeated number of times over with every mother-to-be and yet remains an intensely intimate and subjective experience. Towards the end of this section she realises she has “outdistanced her anxiety” and wants the second child.

In the second section the narrator introduces her grandmother, Doctor K, and Sigmund Freud — both psychoanalysts. Her childhood memories of spending holidays with her grandmother who worked as a professional psychoanalyst while caring for her granddaughter and on those rare occasions for her own daughter. The narrator recalls her mother telling her how when she was a five year old girl her mother, Doctor K, would insist upon analyzing her dreams. Result was the little girl stopped dreaming! It is a jumble of memories shared by the narrator that are at once intimate and intertwined and yet involving distinct individuals and personalities, much as in the way the network of blood vessels connect the unborn baby in the womb to its mother. Similarly Sigmund Freud’s biography and analysis of his patients including daughter Anne are interspersed with that of the personal narrative.

…the past is as prosaic as the future and the facts about it only so much stuff. To pick through dusty boxes, to sift through memories which fray and tear like ageing paper in an effort to find out who we are, is to avoid the responsibility of choice, since when it comes to it we have only ourselves, now, and the ever-narrowing come of what we might enact. Growing up, I said, is a solitary process of disentanglement from those who made us and the reality of it cannot be avoided but only, perhaps, deferred … .

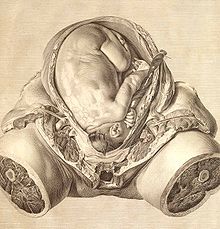

Plate VI of “The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus” (1774) by William Hunter, engraving by Jan van Rymsdyk.

In the third section the narrator is pregnant and waiting to give birth so a lot of time is spent in hospital waiting rooms awaiting tests. She intersperses her reflections with that of the eighteenth century Scottish surgeon John Hunter who was also known for his phenomenal collection of specimens. He was very keen to know about anatomies and would pay gravediggers to get him bodies from fresh graves so that he could dissect them and study the anatomy. He worked closely with his brother William Hunter who had in fact introduced him to the medical sciences. The dissections were conducted in the basement of William Hunter’s Convent Garden house where the brothers were inevitably accompanied by the artist Jan van Rymsdyk who rapidly sketched as evident in the illustration on the right.

The Oxford English Dictionary definition of “Sight n. the faculty or power of seeing”. Jessie Greengrass studied philosophy in Cambridge and London. Her novel Sight is a literary example of psycho-geography — a combination of personal reminiscences and factual historical content. It is also an attempt to get at a further truth which is about how we see one another and we see ourselves especially the female experience which is most often taken away from human experience. ( Interview with BBC Radio 4, February 2018) It is a constantly evolving process of the individual’s subjectivity vs objectivity. It was first discussed in a similar meditative fashion by the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Biographia Literaria. It is unsurprising given that Coleridge too like Jessie Greengrass was inspired by John Hunter’s work and its focus on the distinctions between life and matter. As Jessie Greengrass remarks in her BBC interview “having a subjective self is something which allows us privacy but also separates us even from the people we are closest to” and this is the angle she explores as a novelist in her powerful debut Sight.

Sight has been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2018 and the winner will be announced on 6 June 2018. This will be a close finish since the other contenders for the prize are equally strong and experienced women writers.

Sight has been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2018 and the winner will be announced on 6 June 2018. This will be a close finish since the other contenders for the prize are equally strong and experienced women writers.