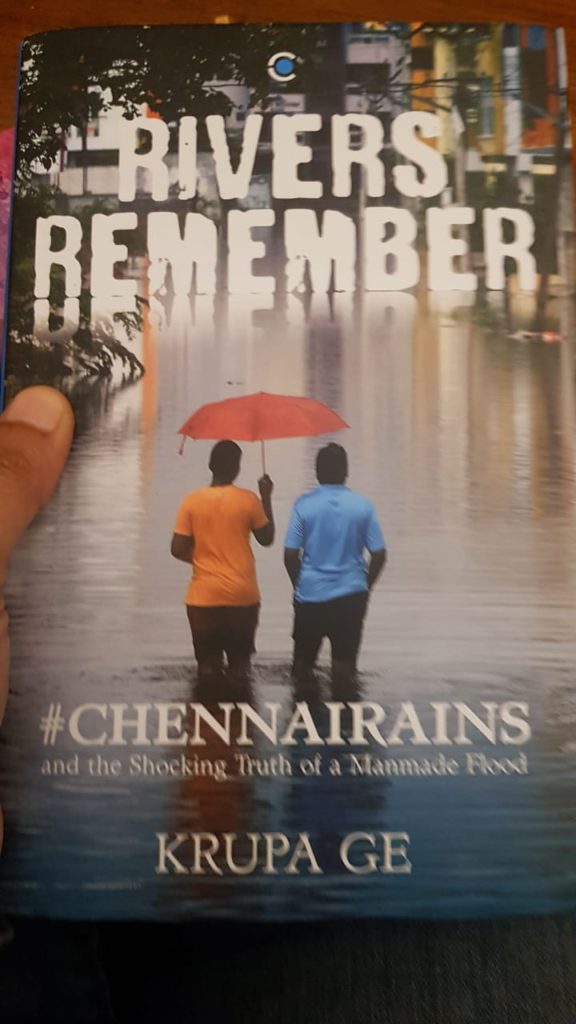

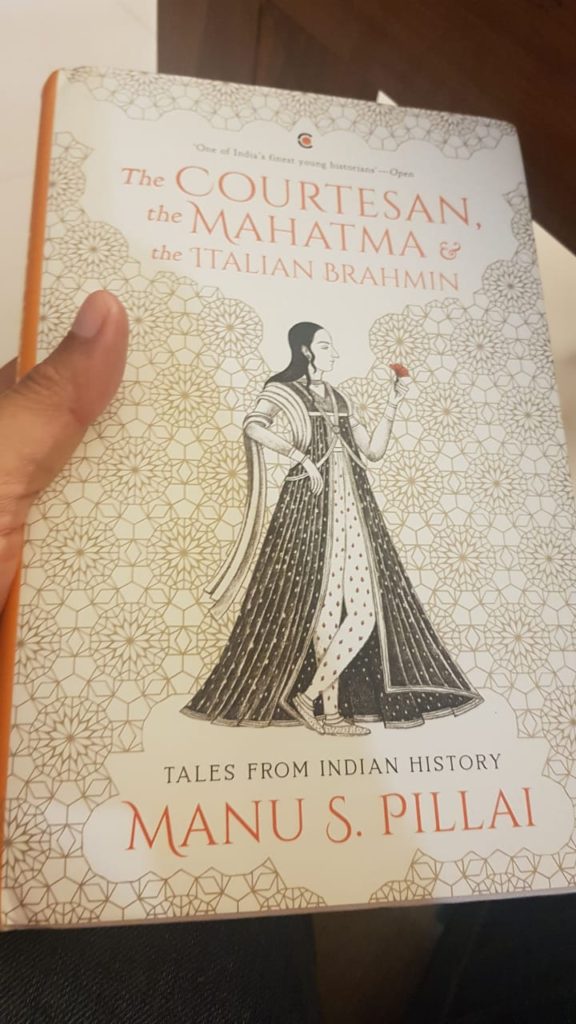

Krupa Ge “Rivers Remember” and Manu Pillai “The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin: Tales from Indian History”

Non-fiction books are the biggest sellers in the Indian book market. A testament to this fact are the number of books being commissioned. Take for instance two recent Westland/Amazon publications. Immensely readable and well-written books by award-winning authors — Krupa Ge’s Rivers Remember: The Shocking Truth of a Manmade Flood and Manu Pillai’s The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin. It is fairly obvious why they would capture the lay reader’s imagination. They are easy books to dip into with plenty of anecdotes.

Manu Pillai’s The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin has fascinating essays about figures from India’s history. It is primarily a collection of his articles from the weekly column he writes for Mint. So each essay is a self-contained story. It is a mixed bag of characters from rajahs and sultans, maharanis and begums, politicians, travellers, courtesans, devdasis and plenty more. The chapter headings are very inviting as well such as “The Italian Brahmin of Madurai”, “Rowdy Bob: The victor of Plassey”, “A Forgotten Indian Queen in Paris” and “The Seamstress and the Mathematician”. As he says in his introduction:

We live in times when history is polarising. It has become to some an instrument of vengeance, for grievances imagined or real. Others remind us to draw wisdom from the past, not fury and rage, seeing in its chronicles a mosaic of experience to nourish our minds and recall, without veneration, the confident glories of our ancestors. The collection …tells stories from India’s countless yesterdays and of several of its men and women. It is an offering that seeks to reflect the fascinating, layered, splendidly complex universe that is Indian history at a time when life itself is projected in tedious shades of black and white. There is much in our past to enrich us, and a great deal that can explain who we are and what choices must be made as we confront grave crossroads in our own times.

In his column “Why women hold the key to a new India” ( 29 June 2019, The Mint) Manu Pillai adds, “The colonizing of Indian minds in the colonial era by Victorian sensibilities was severe, added to which is generations of patriarchy—it will take time and patience before change comes to how history is imagined. Clubbing a courtesan with a mahatma may not immediately be understood or approved of by some. But that is precisely where the courtesan belongs, for, in the larger scheme of things and the big picture of our civilization, her role is no less significant than that galaxy of saints and monks we have all been taught to venerate.”

This is a magnificently well researched book where the lack of bibliographical citations to corroborate the quotes used in the text is an oversight that was not to be expected. For instance, the chapters on “William Jones: India’s Bridge to the West” and “A Brahmin Woman of Scandal” quote Jawaharlal Nehru and E.M.S. Namboothiripad respectively but there is no citation given. This despite every chapter having its own bibliography; yet these two men are quoted but not included in the bibliography. Compare this to the recently published Richard Evans Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History where even when Prof. Hobsbawm himself is quoted in the text, Richard Evans footnotes every quote with the relevant citation.

The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin is a pleasure to read in snatches. To read it from cover-to-cover would be too noisy as there are far too many characters from different periods of history and different backgrounds. But to read a couple of essays at a time is a delight. The book has been fabulously illustrated with charcoal drawings by Priya Kuriyan.

Award-winning journalist Krupa Ge’s Rivers Remember: The Shocking Truth of a Manmade Flood was probably spurred by the devastating loss of her parents’ home in the 2015 Chennai floods. It is a slim book that is more a heartfelt reaction to the floods. Here is an extract from the book published in The Wire. It has plenty of anecdotes with responses to the floods. Here is a witness account of the floods published on 11 December 2015 in the Hindu Businessline. While it encapsulates the immediacy of the moment it also highlights the dangers that the residents faced during the floods. Unfortunately the book publication is a missed opportunity as it could have been used to discuss in greater detail Chennai’s water problems, perhaps even included a thematic map or two depicting the natural waterbodies upon which the local population depended, the water consumption patterns and location of natural aquifers; instead there is one map of Chennai from 1914 as a frontispiece. Writing a book on a natural disaster requires a fair bit of understanding of the various issues at stake. A critical area is that of gender issues in disaster management. It is imperative that it is understood for immediate relief efforts but also if it is to be analysed with hindsight in a book such as this. For example, instead of stating in a one-sentence paragraph “Srinivasan and his friends rescued a new mother of twins and took her to safety with great care”, this could easily have been expanded upon to discuss the many issues involved in such a rescue mission. To quibble about the improvements a book could consider are an indication too of the author’s capabilities. The dissatisfaction as a reader stems from is that the potential is visible but has not been exploited to the hilt.

While both the books are fascinating to read perhaps the editors could have guided the writers a little more. The birth of every book is a constructive process between the author and the editor. It is a coming together of expertise to make a product that will hopefully be read by many. Both these books are timely and relevant but would definitely have benefitted by editorial advice to add more value to their texts. While non-fiction sales are booming it is a good idea to pause and reflect upon the importance of bringing to the fore academic editing skills while editing books that are positioned for a trade list and a lay reader. Cross-pollination of such skills is increasingly becoming a crying need as the boundaries between subjects that were previously considered to be exclusive academic domains make their way into trade lists and general book markets.

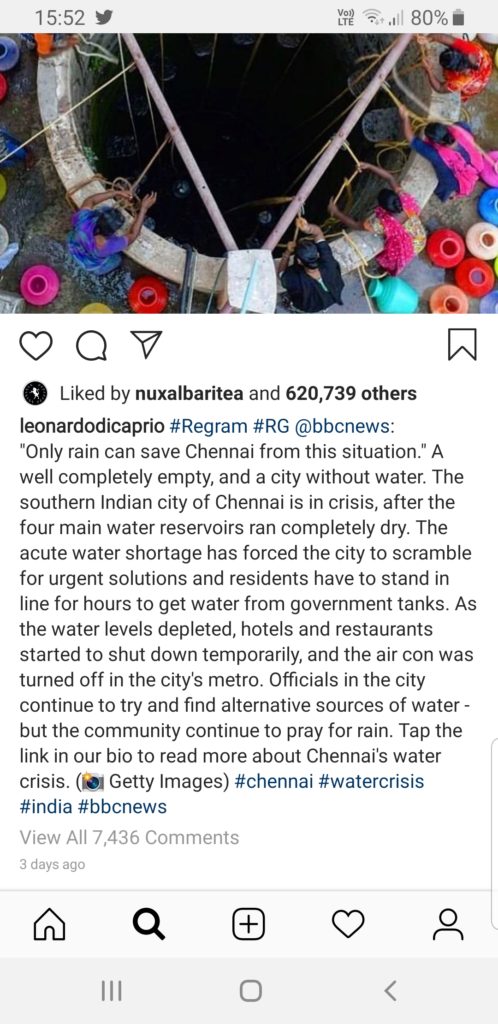

Despite these slight “technical” hiccups these books are must reads. Manu Pillai’s The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin is unputdownable and Krupa Ge’s Rivers Remember: The Shocking Truth of a Manmade Flood as Jnanpith winner 2018 Amitav Ghosh says is an “absolute must read…[for] it brings …the full horror of the catastrophe”. More so when three and a half years later Chennai is facing a drought — a crisis highlighted by Hollywood actor Leonardo di Caprio’s in his instagram post.

30 June 2019