Interview with award-winning New Zealand author, Gavin Bishop

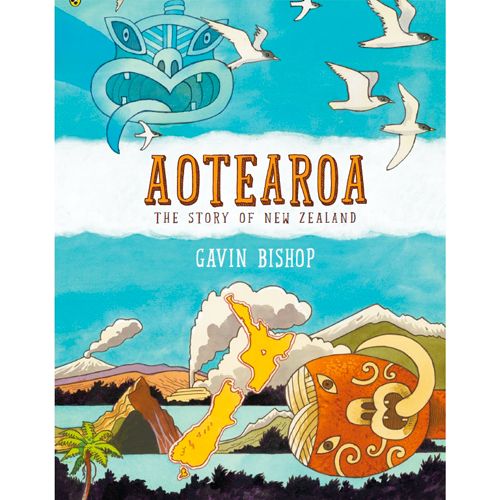

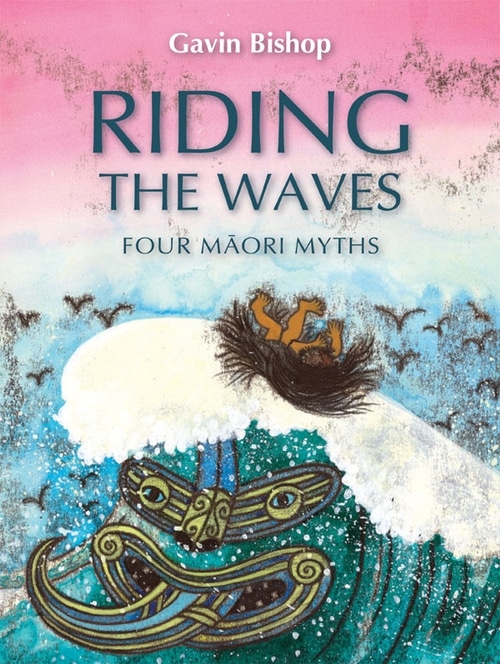

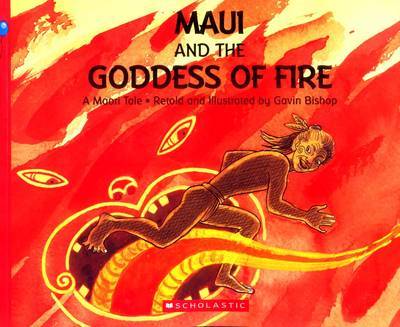

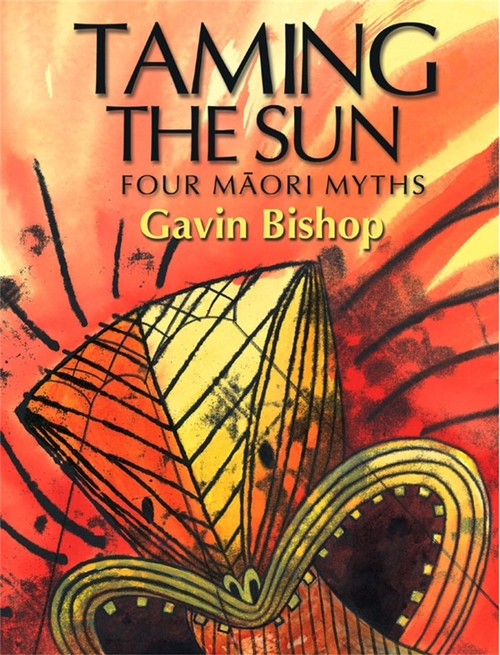

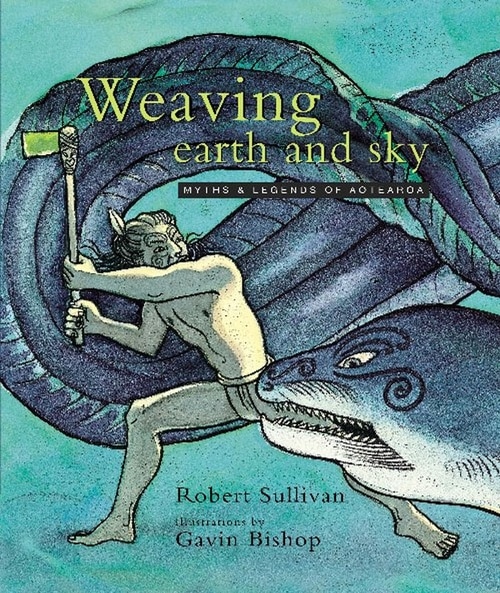

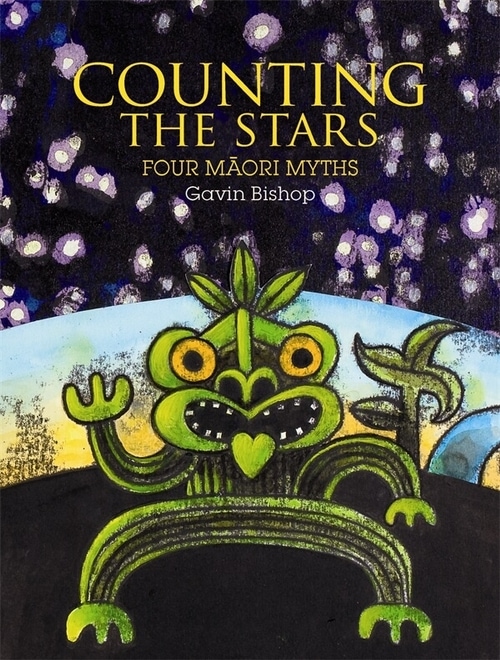

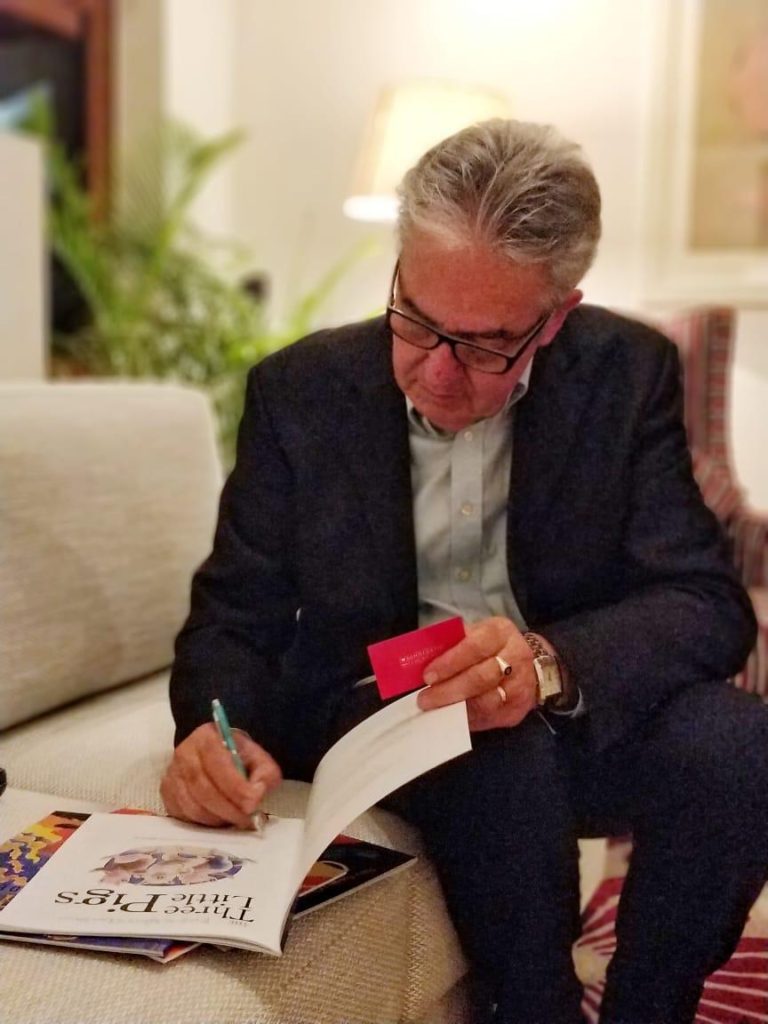

In December 2018, award-winning New Zealand children’s writer Gavin Bishop was invited to India by the New Zealand High Commission for an author tour. Gavin Bishop is an award winning children’s picture book writer and illustrator who lives and works in Christchurch, New Zealand. As author and illustrator of nearly 60 books his work ranges from original stories to retellings of Maori myths, European fairy stories, and nursery rhymes. Gavin Bishop participated in the Bookaroo Children’s Literature Festival as well as travelled with his publisher’s, Scholastic India, to various schools for exciting interactions. I met Mr Bishop and his wife, Vivien, at the New Zealand Deputy High Commissioner’s, Suzannah Jessep, residence. It was a lovely evening of freewheeling conversation about books and publishing, children’s literature, creating picture books and the power of stories. Excerpts of an interview are given below.

Here is a picture taken at the Deputy High Commissioner’s residence along with Gavin Bishop. It has been uploaded on the Facebook page of the New Zealand High Commission to India- How would you define a children’sbook especially a picture book as you make them the most often?

A children’s book is one that speaks honestly to childrenwithout pretentions. The worst kind of books are those that pretendto be for children but are really aimed at the parent or adult reading the bookto the child.

Apicture-book is one where the pictures and words tell a story, ‘hand-in-hand’.Neither the pictures nor the text are ’top-dog’, neither one is moreimportant than the other. Both parts have separate jobs to do to tell thestory. The picture book is my passion. It offers so many artistic and literarychallenges that I could never exhaust them all in a single lifetime. Manypublishers, mostly in the USA, have said to me that picture-books arequite simply for children who can’t read yet. I can’t think of anything furtherfrom the truth. There are lots of examples of picture books that work at manylevels and can be re-read over and over again by children of all ages. Ithink my version of The House that Jack Built that looks atthe colonisation of New Zealand by the British in the early 19th century, is a picture book that appeals to older children, children who can certainly read. Many New Zealand schools use this book at upper levels to talkabout the history of this country.

2. How do you select the stories you choose to write about? Where did you hear the stories that you write about in your books?

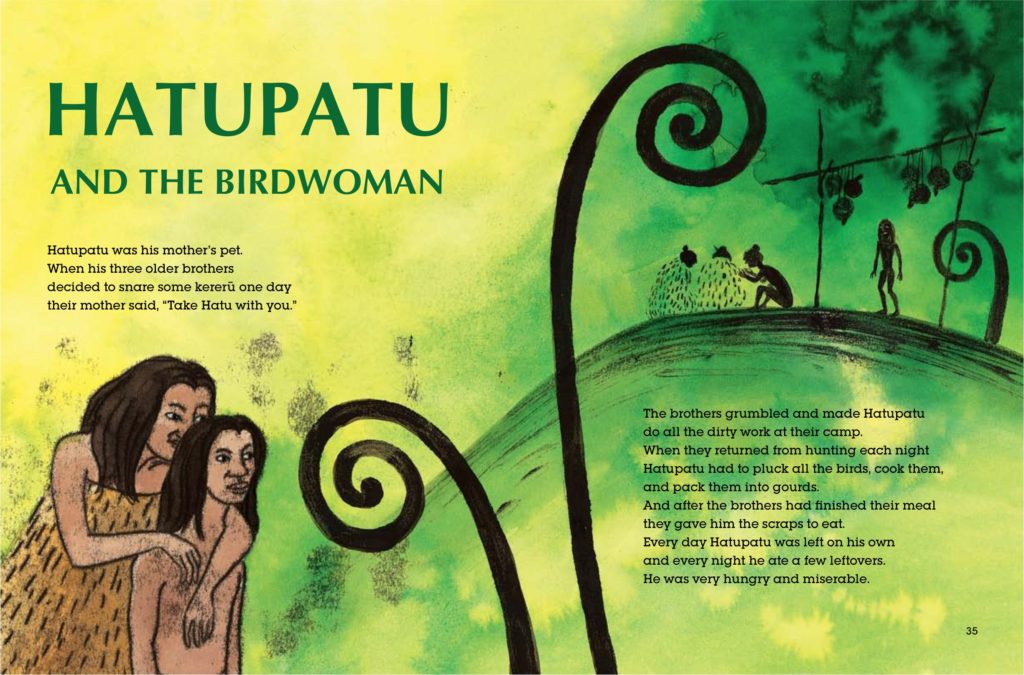

For stories, I constantly revisit all the terrific folktales, myths and legends ofthe New Zealand Maori as well those from Europe. When I rewrite a story, I tryas much as possible not the change the plot or the outcome. If it isa little frightening, I leave it like that. But if I think aparticular story is more suited to adults, as many traditional storiesare, then I don’t choose it. There are lots of adventures for example, that the Maori demi-god Maui has, that I think are extremely interesting but theycontain adult elements that a child does not to be confronted with yet.

My childhood is another very deep pool full of memories and stories that I diveinto from time to time.

Most of my books take a long time to produce. My pictures are often full of detailand are drawn by hand on paper as opposed to beingcomputer-generated. If I am to live with a creation for most of a year, Ihave to be convinced from the start that the story is worthwhile and willadd something to a child’s life. I know that sounds lofty, but I really believe that as a writer for children my obligation is to present a young reader with stories and ideas that they will find interesting and perhaps have not heard of.

Another huge source of inspiration is reading. I try to read a lot of fiction. Movies are a good source of ideas too. In fact a movie is rather like a picture book except instead of text as in a book, you have dialogue. Some of the movies I seen over the years have never left me. I have beenparticularly inspired by movies I saw as a young adult. Films by Fellini, Bergman, Pasolini and Altman showed me how stories can be told using vivid imagery and characters.

3. Did you consciously choose the style of writing for children as you do in your longer pieces of fiction –simple sentences, very short chapters, precise descriptions with few polysyllabic words?

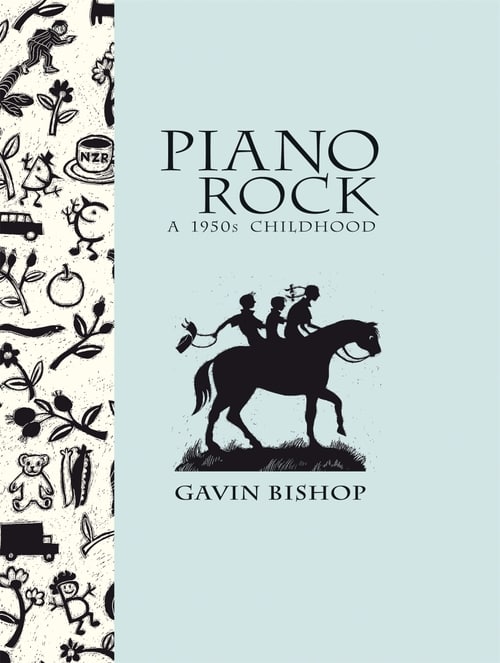

When I write I do keep in mind that I am writing for children. But this is onlyreflected in the style and format. I try not to modify the story or the humour which can result in ‘talking-down’ to the reader. Although I usesimple sentences and short chapters I don’t shy away from difficult words if I think they are the right ones for the job. When I wrote Piano Rock I probably had 7 or 8-year-old readers in mind. I have been heartened by thenumber of young boys who have written to me to say Piano Rock is the first book they have read right through. I would like to think that thiswas because of the content, but I suspect it had something to do with thefact the book is full of short sentences and quite a few pictures. It is very non-threatening to a reluctant reader. No sooner have you started a chapter than you find yourself finishing it.

4. Piano Rock and Teddy One-Eye focus a bit on the stories narrated to you by your mother and grandmother but your repertoire indicates that this love for stories go fardeeper. When did this love for stories begin and do you still collectstories?

These two books are about me. They are my autobiographies, even though the second one waswritten by my 68-year-old teddy bear. I vividly remember sitting with my grandmother by the fire listening to her reading me stories and singing strange little songs that she plucked out of her memories of when she was a child. One I remember more than all the others, and one I included in Piano Rock was – “Old Mrs Bumblebee said to me the other day, comeand have a cup of tea on the back veranda.” That’s all there is to it, but at the age of 3 or 4 I found it for some reason, intriguing. I can remember trying to make sense of it byputting it into the context of our neighbourhood. “Did Mrs McQuirter overthe back fence invite us over for a cup of tea?” I wondered quietly to myself.

This little ditty has been with me all of my life and I have, in my quest to find itsorigin, mentioned it to lots of people. All have replied they had never heardof it until one day at a talk I was giving an Indian woman stood up in theaudience and said she had heard it in India when she was child.Perhaps the word ‘veranda’ is a clue? The mystery deepens……,

5. How would you define a compelling story?

The best stories are the ones that become part of you for the rest of your life. I think this happens more often in childhood, therefore it is even more important for a children’s writer to put everything they have into producing the best story they can.

6. The imagery in your books is fantastic. It’s almost as if the imagery used complements the illustration. Was that deliberate or an unconscious act?

I am a very visual person and when I’m writing I see everything that is happening in my mind’s eye. I plan my text and illustrations carefully to begin with but after that, when it comes to painting and writing, I rely a great deal on my subconscious. I follow my gut-instinct and often cannot tell whether a picture or a piece of writing has worked until I distance myself from it by leaving itfor some time and not looking at it.

7. How do you conceptualise a book?Is it taking into account the text and the illustration? How does the illustration process evolve?

To beginwith I am directed by format. If it is a picture book, then I know from thebeginning it will most likely have 32 pages. I generally begin with the storyand write it with the length of the book in mind. I have now developed a spare writing style for this sort of book where I deliberately keep description for example, to a minimum so as to allow plenty of room for the illustrations to tell their parts of the story. Sometimes I jot down little ideas for the pictures in the margin as I write. The process at this stage of the book is quite measured. Once the text reaches a stage that I thinkis workable, I draw up a storyboard, a page by page plan from cover to cover ofthe whole book. I usually keep this small, drawing the whole thing onto a single A2 sheet of paper, so that when it comes to putting images into place on the miniature pages I cannot get into too much detail. This results in stronger compositions when these little pictures are increased tofull size later, when I make a dummy. I work in pencil which I go overwith ink. The dummy is based on the page size supplied by the publisher afterreceiving a quote from the printer. I make a dummy with 10 sheets of paperfolded in half. That gives you 32 pages plus endpapers and cover. Next I print off the text and glue it into place throughout the book. This instantly showsme how much space is left for the illustrations. The next couple of months arespent enlarging and drawing the pictures from the storyboard into the dummy. This is really where all the hard work begins. If it is a historical story I do most of my research at this stage.

A completed dummy is useful for showing your publisher what you have in mind for the book it also provides a detailed guide for the next process of producing the finished art work. From the start to publication a picture book usually takes a year.

8. How does your Maori ancestry inform your art of storytelling and fascination of folk tales?

My Maori ancestry tells me who I am and where I belong. Aotearoa/New Zealand is myturangawaewae, my place to stand in the world. I have European ancestry as well and that has given me literature and language but to know that some of my tupuna/ancestors have lived in the South Pacific for thousands of years and I live here now, gives me a great sense of belonging. My mother’s name was Irihapeti Hinepau and her father gave her those names because they areancestral names. I have a large number of relatives in Aotearoa who trace theirancestry back to people in the past who have these names too. Maori myths and legends are as rich and profound as any in the world, yet when I was a child we were told more about the myths and legends from Greece and Rome than the stories from our part of the world. New Zealand has for too long suffered from a cultural cringe, always looking North to the rest of the world for affirmation. As a re-teller of Maori myths for children I want to help the next generation become proud of being part of this country. I want them to know their stories and be made strong by them.

9. How did you get into bookmaking? Have you collaborated with other writers and illustrators?

In the 1960s I went to the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts and studied painting. While I was there I was fortunate to be taught by Russell Clark, a well-known New Zealand artist with a particular interest inillustration. He saw I was interested in children’s picture books and he encouraged me to pursue that interest. It was not until the late 1970s that I did something about this interest and tried writing my first book, Bidibidi.

My ideal project is one where I write and illustrate my own book, but I have, from time to time, worked with others. Some years ago I wrote about 30 or 40 ‘readers’. Because a lack of time these were illustrated by a series of international artists and published all over the world.

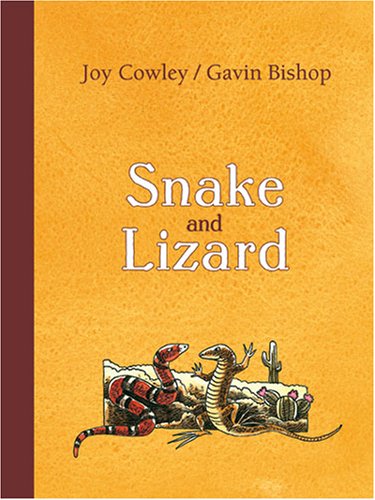

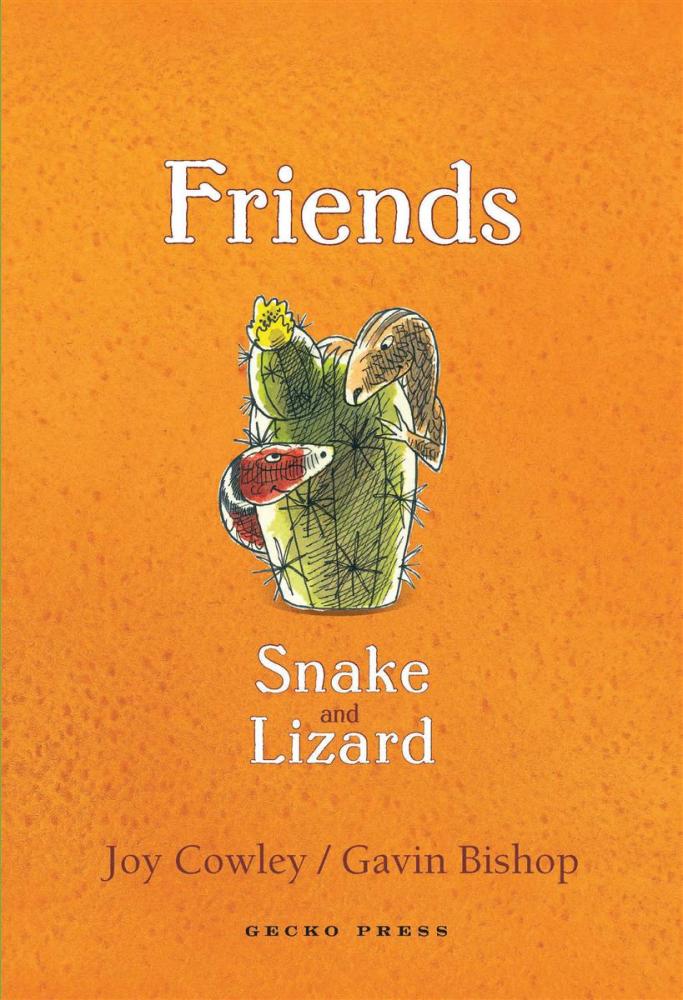

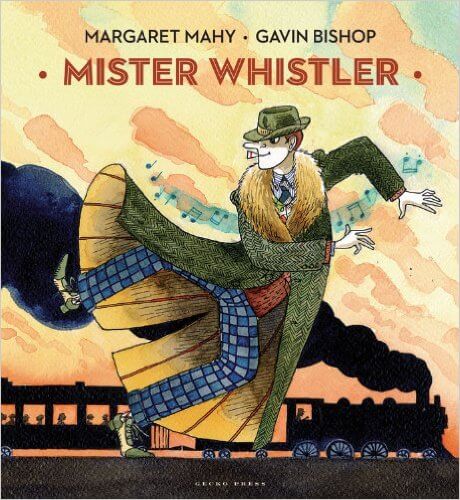

I have also illustrated books for other writers. I have done quite a few with Joy Cowley, the most successful being the Snake and Lizard series. And Margaret Mahy and I worked on what was probably her last book before she died — Mister Whistler .

10. Do your books travel to other book markets in English and have they been translated?

My books have been sold all over the world, particularly in England, Australia and the USA. Some of my books have been translated into Spanish, French, Italian, Danish and other European languages. Recently my books have become very popular in Asia and several of my recent publications appearin Korean, Mandarin and Japanese editions.

Some ofmy books, such as Kiwi Moon and Hinepau have been adapted for the stage. Kiwi Moon travelled nationally as puppet theatre and the third adaption of Hinepau was performed entirely in Maori.

But oneof my biggest creative challenges was writing the story and designing the sets and costumes for two ballets for the Royal New Zealand Ballet Company. Although they were pitched at an audience of children they were performed by the regular company of dancers with whom I got to work. Original music was composed by a musician friend and the choreography was designed by one of New Zealand’s top dancers. Attending the opening performances of these ballets that were created in consecutive years, were two of the most exciting experiences of my life.

Watch Shantanu Duttagupta, Head of Publishing, Scholastic India interview Gavin Bishop at the New Zealand High Commission.

In Conversation with Gavin BishopWe met author Gavin Bishop and discussed books, writings and much more!Big Thanks to: New Zealand High Commission to India, Bangladesh, Nepal & Sri Lanka Scholastic New Zealand

Posted by Scholastic India on Monday, December 10, 2018

14 December 2018