Press Release: HACHETTE INDIA TO RELEASE HARRY POTTER AND THE CURSED CHILD PARTS I & II SCRIPT BOOK

HARRY POTTER AND THE CURSED CHILD

PARTS I & II SCRIPT BOOK

Little, Brown Book Group announces today that they will publish the script book Harry  Potter and the Cursed Child Parts I & II, an original new story by J.K. Rowling, Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, a new play by Jack Thorne written to be enjoyed on stage. The Special Rehearsal Edition of the script book (hardback, £20) will be published at 00.01 on 31st July 2016, following the play’s opening on 30th July, bringing the eighth Harry Potter story to a wider, global audience. The script eBook will be published simultaneously with the print editions by Pottermore, in collaboration with Little, Brown Book Group in the UK, and Scholastic in the US and Canada.

Potter and the Cursed Child Parts I & II, an original new story by J.K. Rowling, Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, a new play by Jack Thorne written to be enjoyed on stage. The Special Rehearsal Edition of the script book (hardback, £20) will be published at 00.01 on 31st July 2016, following the play’s opening on 30th July, bringing the eighth Harry Potter story to a wider, global audience. The script eBook will be published simultaneously with the print editions by Pottermore, in collaboration with Little, Brown Book Group in the UK, and Scholastic in the US and Canada.

David Shelley, CEO of Little, Brown Book Group said: ‘We are so thrilled to be publishing the script of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. J.K. Rowling and her team have received a huge number of appeals from fans who can’t be in London to see the play and who would like to read the play in book format – and so we are absolutely delighted to be able to make it available for them.’

About the book/play:

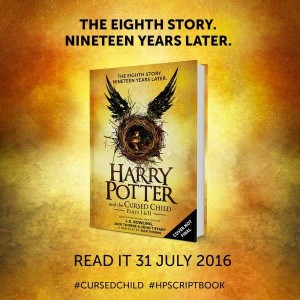

The eighth story. Nineteen years later.

Based on an original new story by J.K. Rowling, Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a new play by Jack Thorne, is the first official Harry Potter story to be presented on stage. It will receive its world premiere in London’s West End on 30th July 2016.

It was always difficult being Harry Potter and it isn’t much easier now that he is an overworked employee of the Ministry of Magic, a husband, and father of three school-age children.

While Harry grapples with a past that refuses to stay where it belongs, his youngest son Albus must struggle with the weight of a family legacy he never wanted. As past and present fuse ominously, both father and son learn the uncomfortable truth: sometimes darkness comes from unexpected places.

- The Special Rehearsal Edition of the Harry Potter and the Cursed Child script book will comprise the version of the play script early in the production’s preview period, several weeks prior to the opening performances. The preview process allows the creative team to rehearse changes and/or to explore specific scenes further, in front of a live audience, before the official opening performances on Saturday 30th July. As such the script is subject to change after the Special Rehearsal Edition is published, which is why this edition will only be available for a limited time, to be replaced by the Definitive Collector’s Edition at a later date. More details about the Definitive Collector’s Edition will be announced in due course.

- J. K. Rowling is the author of the bestselling Harry Potter series of seven books, published between 1997 and 2007, which have sold over 450 million copies worldwide, are distributed in more than 200 territories and translated into 79 languages, and have been turned into eight blockbuster films.

She has written three companion volumes in aid of charity: Quidditch Through the Ages and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them in aid of Comic Relief; and The Tales of Beedle the Bard in aid of her children’s charity Lumos.

In 2012, J.K. Rowling’s digital entertainment and e-commerce company Pottermore was launched, where fans can enjoy her new writing and immerse themselves deeper in the wizarding world.

Her first novel for adult readers, The Casual Vacancy, was published in September 2012 and adapted for TV by the BBC in 2015. Her crime novels, written under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, were published in 2013 (The Cuckoo’s Calling), 2014 (The Silkworm) and 2015 (Career of Evil), and are to be adapted for a major new television series for BBC One, produced by Brontë Film and Television.

J.K. Rowling’s 2008 Harvard commencement speech was published in 2015 as an illustrated book, Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and the Importance of Imagination, and sold in aid of her charity Lumos and university–wide financial aid at Harvard.

In addition to J.K. Rowling’s collaboration on Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Parts I & II, an original new story by J.K. Rowling, Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, a new play by Jack Thorne, she is also making her screenwriting debut with the film Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, a further extension of the wizarding world, due for release in November 2016.

Avanija Sundaramurti, Head of Marketing: [email protected]

Nupur Kumar, Marketing Executive: [email protected]

Shobhita Narayan, Marketing Executive: [email protected]

10 February 2016