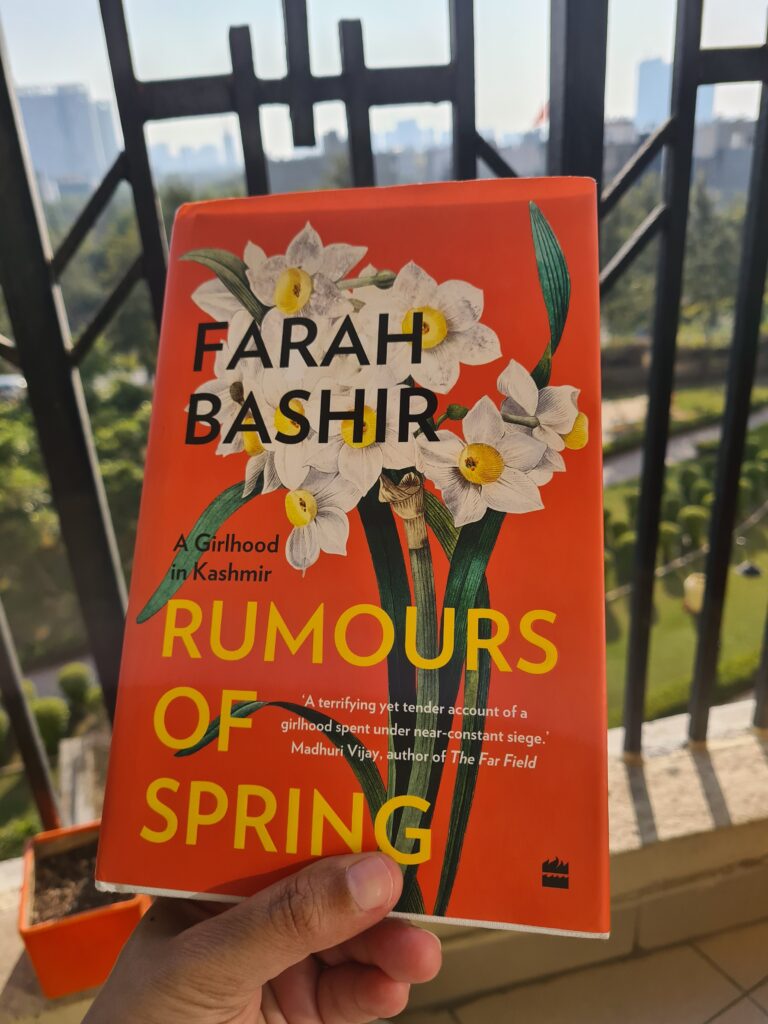

Farah Bashir’s “Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir”

Farah Bashir’s memoir Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir ( Harper Collins India) is an extraordinary book. While keeping vigil by her grandmother’s body, the older Farah Bashir recounts her childhood memories of living under siege in Kashmir. These events are interspersed with stories that her grandmother told the young Farah.

I read Rumours of Spring a long time ago but there are some books that make it impossible to write about immediately. This is one of them. This book brought back memories of my trips to Kashmir. I was able to travel to the state with my father as he was a Customs & Central Excise officer and his beat included Jammu & Kashmir when he was posted as Chief Commissioner, Customs, Amritsar. We visited places in the state that were mostly inaccessible. Those trips were unforgettable. The stunning beauty of Kashmir are of course talked about but what really struck me in those trips were to see signs of conflict everywhere. For instance, the empty bottles and tin cans that were strung at regular intervals on barbed wire fencing. These could be around fields or properties or simply rolled up wire being used as barricades. The idea being that if anyone tried crossing these wires, there would be a clatter and a bang and the security forces on patrol would be alerted. The normalisation of this constant state of alert was unsettling. We would only visit the state for a few days at a time but I could never get over the fact that this was the way the locals lived 24×7. There have been many firsthand accounts of living under siege in Kashmir. It never fails to disturb. Farah Bashir’s book is a fine addition to the list. It is particularly unnerving to read it as she recounts much of what is in our living memory. At the same time, it brings back memories of other similar situations. For me, for example, it is witnessing the riots of 1984 in Delhi, after the assassination of the prime minister Indira Gandhi. Recalling the anxiety of my grandparents who had lived through Independence and the subsequent riots. So the moment, news broke, my grandmother sent my brother and me to buy provisions and stock up. My grandfather, N.K. Mukarji, who was a young ( and the last) ICS officer of the Punjab cadre in 1947, helping government teams manage the division of Punjab, was suddenly remembering incidents of 1947 that were eerily similar to 1984. Later, we were staying with our father in Shillong and we witnessed the flag marches the Army carried out and how society was brought to a standstill. Buying basic provisions became a feat to achieve. Much later, I recall watching the demolition of Babri Masjid on television on 6 Dec 1992, followed by the maha artis in Maharashtra and the rising communal tension in Delhi. Then of course, we have had many more incidents of violence that are too horrific to recount. Reading Farah Bashir’s book during the pandemic brought it all back in flurry. But it also made apparent the parallels between our pandemic way of living with that of life in a conflict zone. Without sounding callous, the difficulties in trying to manage daily life while constantly living with uncertainty and never too sure when systems will be brought to a grinding halt, makes the individual anxious. Yet, there are even more chilling parallels between what Farah Bashir witnessed as a child in Kashmir with Nazi Germany. For instance, security forces pulling out men from their home and making them assemble in large fields in an attempt to identify “militants”.

It was during one winter morning in 1990. Ramzan Kaak had gone out to buy bread but was sent back by the troops even before the announcement was made. The announcement, usually made twice, in Urdu and in sometimes Kashmiri, sounded more like a threat: ‘Apne gharoon se baahar niklaliyey. Koi aadmi ghar pe na paaya jaaye.’

Mother, Bobeh and I huddled in our living room, while Ramzan Kaak and Father left the house to be assembled in a large ground of a public school nearby, alongside all the other men from the neighbourhood. The morning passed in a daze, punctuated with the abrupt thuds of doors being slammed and the sound of steel utensils being flung about. Later, of course, these would become the all too familiar ‘crackdown noises’.

That morning we felt completely numb, unable to move around; we didn’t get any work done, nor speak to each other. ‘The trepidation of our turn being next induced a sickness. I felt completely nauseous. Towards afternoon, the troops walked into our courtyard. Mother and Bobeh turned paler upon seeing them. I too must have looked like them. I do remember feeling dizzy and light-headed.

Suddenly, the appearance of our frail neighbour, Ghaffur, added some confusion to the already tense situation. Why was he with them? Both Mother and Bobeh wore a quizzical expression upon seeing him.I too was thoroughly puzzled to see Ghaffur with the troops. But I didn’t dare to ask anyone anything. The expression on his face was unforgettable. He looked almost dead, like a body that was breathing. His face had ashedned, and his lips were taut and white.

After the troops walked nitou our kitchen wearing muddy boots, soiling everything, they flung open the cabinets. Upon discovering the trapdoor on the floor –the voggeh — they went berserk! They ran amok with suspicion, as if they’d unearthed a tunner to the other side of Kashmir, in Pakistan. Quickly, they broke into two batches: one group cordoned off the house from the outside in the courtyard and the other lot disappeared into the voggeh, into what they seemed to assume to be an imaginary escape tunnel. They did not expect it to be an ordinary floor of an ordinary home with ordinary things. They ventured into the ground floor vehemently, and because they couldn’t find anything there, they ransacked the gaan. Suspecting militants to be in hiding behind the gunny sacks, they poked the bayonets of their rifles into them. They slashed upon the large rice bags, callously unleashing rivers of grains on to the part-stone, part-mud storeroom floor. They scattered chunks of coal that were hoarded in large tin drums by overturning them. Perhaps it was the adrenaline from discovering the mysterious door that led them nowhere, or their hurt pride and disappointment for not having recovered any arms, ammunition or even militants from our home. When they left, they left behind nothing but misery that was pasted on to the floors and walls of our house. A misery that couldn’t be wiped away.

Since that first time, Mother remained stoic when the troops searched our house. Soon after they’d leave, she’d take stock of the destruction and then, break down. That afternoon, however, seeing our storage room turned upside-down, we succumbed to a deep despair after. To clean up after the crackdown wasn’t easy. While the scattered wooden logs could be picked up and stacked back into tall columns, the task of separing bits of coal from rice grains brought me to tears of helplessness and frustration.

….

That day in 1990, when Father and Ramzan Kaak returned in the evening, we heaved a sigh of relief. Father didn’t speak much. Ramzan Kaak told us how the men were paraded in front of a Gypsy that had an informer sitting inside, whose job was to identify militants and militant suspects. The latter could be anybody. All of this would be routine in a few month. That day, as Father locked the house, he remarked onthe uselessness of bolts and doors. Even I had understood by then that their safety was by no means guaranteed and that just because the men had been assembled, there was no assurance that they’d return together or return at all.

Each time a house was searched and found ‘clean’ — that is, no arms or ammunition was recovered — a date was inscribed on the facade of the house, usually near the main gate. Our house, being in the heart of downtown, had accumulated nine such dates in less than four months.

(p.96-99)

There are many more passages that I can quote but this long extract is sufficient. It gives a sense of the violence that Farah Bashir and rest of Kashmir faced on a daily basis. The disruption to normal life. Living in constant fear. Living in constant anxiety. Living with uncertainy; not knowing what will come next. Feeling nauseous. This is a neverending cycle that has not as yet come to an end. Decades later, on 29 Jan 2022, Farah Bashir said in a conversation organised by the Hyderabad Literature Festival that for the first time, the various aches and pains she had been experiencing were greatly reduced. The trauma of constantly living in fear had had its physical impact on the child and later adult but writing this book was therapeutic. It had literally helped ease some of her pain. Small mercies in otherwise bleak times.

Read Farah Bashir’s Rumours of Spring. It is unforgettable.

20 Jan 2022