Devashish Makhija’s debut collection of stories, Forgetting, has been published by HarperCollins India. It consists of 49 “stories”. After reading the book, I posed some questions to the author via email. His responses were fascinating, so I am reproducing it as is.

Devashish Makhija’s debut collection of stories, Forgetting, has been published by HarperCollins India. It consists of 49 “stories”. After reading the book, I posed some questions to the author via email. His responses were fascinating, so I am reproducing it as is.

1.Over how many years were these stories written?

I always find it difficult to answer such a question. There are so many ways to measure the time taken to ‘create’ a body of work. Least of all is the time taken to physically ‘write’ the stories. So I’ll attempt a two-tiered response.

Literally speaking, these stories were written sporadically over a 6-8 year period. Creating stories in some form or the other keeps me alive. And it was in this time period that most of the screenplays I’d been writing (for myself to direct as well as for other filmmakers, from Anurag Kashyap to M.F. Husain) were not seeing the light of day. For some reason or the other those films weren’t getting made. So in the slim spaces in between finishing a draft of one screenplay and starting to battle with the next, I kept writing – short stories, flash fiction, children’s books, poetry, essays, anything. I didn’t have a plan for any of these back then. I wrote just so I wouldn’t slit my throat out of frustration!

But this writing turned out to be my most honest, brutal, personal, (dare I say) original. Because, here I wasn’t answerable to anyone – not producers, not directors, not audiences, not peers, no one. So as the years passed, and the shelved films kept piling up, my non-film writing output began growing exponentially. My personal pieces came together in my self-published Occupying Silence. Then a story (“By/Two”) got published in Mumbai Noir. Another (“The Fag End”) came out in Penguin First Proof 7. A third story (Red, 17) published multiple times in several Scholastic anthologies. Two children’s books (When Ali became Bajrangbali and Why Paploo was perplexed) became bestsellers with Tulika Publishers. My flash fiction found a dedicated readership with Terribly Tiny Tales ( http://terriblytinytales.com/author/devashish/ ). And before I knew it a ‘collection’ of sorts had formed. So if I have to put a fairer timeline to the creation of ‘Forgetting’ I will mostly be unable to because this unapologetic, personal story-writing found its seeds in writing I’ve been doing since my teenage years, and most of the themes / motifs in these stories have formed / accumulated within me over the last 20 years perhaps.

- Are these stories purely fictional? There is such a range, I find it hard to believe that they are not based or inspired by real situations you have encountered.

That is a most acute observation. Although these stories have been placed in contexts fictionalized, often these are almost all lived experiences. In fact most of the first drafts of these stories were written in first person. When I began to see them as a ‘collection’ of sorts I went back to most of them and rewrote them as third person narratives, often fleshing out a central character removed from myself. It has been an interesting experiment, to have written something first as my own point of view of a very personal experience, then gone back and shifted the pieces around to see how the same would appear / sound / read if I were to be merely an observer, looking at this experience from the outside, in.

But this is not the case with all stories. Some of these stories were first film ideas / stories / screenplays that I couldn’t find producers for. I rewrote them as prose fiction pieces to attempt turning them into films once they found an audience of some sort through this book. I’m sure you can detect which these were… ‘By/Two’, ‘Red 17’, ‘Butterflies on strings’ – the larger, more intricate narratives in this collection. If I’m not too off the mark these particular stories read more visually too, since they were conceived visually first.

- How did you select the stories to be published? I suspect you write furiously, regularly and need to do so very often. So your body of work is probably much larger than you let on.

That is yet another acute observation. You’re scaring me. It’s like you’re peeking into my very soul here, through this book. I used to (till last year) write ‘furiously’ and ‘regularly’, quite like you put it. Every time I’ve wanted to (for example) kill myself, kill someone else, start a violent revolution, tell a married woman that I love her (or experienced any such extreme anti-social urges) I’ve just sat myself down and WRITTEN. I have unleashed my inner beasts, exorcised my demons, counseled my dark side, purged myself of illicit desire by Writing. So yes, I have much, much more material than this anthology betrays.

But when a book had to be formed from the hundreds of diverse pieces I had ended up creating, a ‘theme’ emerged. And I used that theme as a guiding light to help me select what would stay in this book and what would have to wait for another day to find readership.

This ‘theme’ was ‘Forgetting’.

I found in some of my stories that they were about people (mostly myself reflected in my characters) trying to break out of a status quo / a pattern / a life choice that they’re now tired of / done with / tortured by. The selected stories are all about people trying to break loose of a ‘past’. And these stories – although frighteningly diverse in mood, intent, sometimes even narrative style – seemed to come together under this umbrella theme.

- Who made the illustrations to the book? Why are all of them full page? Why did you not use details of illustrations sprinkled through the text? Judging by your short films available on YouTube, every little detail in an arrangement is crucial to you. So the medium is immaterial. Yet, when you choose the medium, you want to exploit it to the hilt. So why did you shy away from playing with the illustrations more confidently than you have done?

I am now thoroughly exposed. You caught this out. All those illustrations are by me. Some of them are adapted from my own self-published coffee table book from 2008 –Occupying Silence (www.nakedindianfakir.com). That book had served as a catalogue of sorts for the solo show I’d had in a gallery in Calcutta of my graphic-verse work. Some of the writing from that book found its way into Forgetting as well. I hadn’t planned on putting these illustrations in. It was my editor Arcopol Chaudhuri’s idea. The anthology was ready, the stories all lined up, ready to go into print, when it struck him that some visuals might provide a welcome sort of linkage between the various sections of the book. And I jumped at the chance to insert some of my graphic illustrations. I did wonder later that if I had more time I might have worked the illustrations in more intricately. Perhaps even created some new work to complement the stories. But it was a last minute idea. And perhaps that slight fracture in the intent shows. Perhaps it doesn’t. But your sharp eye did catch it out.

What you suggest of detailed illustrations sprinkled right through the text is something I have done in Occupying Silence (http://www.flipkart.com/occupying-silence/p/itmdz4zfanzpcgg7?pid=RBKDHDVKJHW4QEAQ&icmpid=reco_bp_historyFooter__1). I’m a big one for details. It’s always the details that linger in our consciousness. We might be experiencing the larger picture during the consumption of a piece of art, but when time has passed and the experience has been confined to the museum of our memory, it is always the little details that return, never the larger motifs. And I thoroughly enjoy creating those details. In some subconscious way it always makes the creative experience richer / more layered for the reader / audience / viewer. And gives the piece of art / literature / cinema ‘repeat value’. And ‘repeat value’ is what I think leads to a relationship being forged between the creation and its audience. With no repeat value there is no ‘relationship’, there is merely an acquaintance.

So yes, I wish I could have worked the illustrative material into the book more intricately. Next time I promise to.

- In this fascinating interview you refer to the influences on your writing, your journeys but little about copyright. Why? Are there any concerns about copyright to your written and film material? ( http://astray.in/interviews/devashish-makhija )

Always. Film writing almost always presupposes more than one participant in the process. Even if I write a screenplay alone, there will eventually be a director (even if that is myself) and a producer (amongst many, many others) who will append themselves to the final product. Unless I spend every last paisa on making that film from my own pocket (which happens very rarely, and mostly with those filmmakers who have deep pockets, unlike the rest of us) the final product will never be mine alone to own. Where this copyright begins, where it ends; what is the proportion this ownership is divided in; who protects such rights; and for what reasons – are all ambiguous issues, without any clear-cut rules and regulations. I, like everyone else, did face much inner conflict about whether I should go around sharing my written material with people I barely knew, considering idea-thievery is rampant in an industry as disorganized and profit-driven as ‘film’. But soon enough I gave up on that struggle. If my stories were to see themselves as films then they would have to be shared with as many (and as often) as possible, with little or no concern for their security.

What I started doing instead was dabbling in all these other forms of storytelling as well where the written word is the FINAL form, unlike in film, where the written word is merely the first stage, and where the final form is the audio-visual product. And the more output I created on the side that was MINE, the less insecure I felt about sharing the film-writing output I was freely doling out to the world at large.

Shedding the insecurity of copyright made me more prolific I think. Because I had one less (big) thing to worry about.

Also, I believe this whole battle to ‘own’ what you create is a modern capitalistic phenomenon. To explain what I mean let’s consider for a moment our Indian storytelling tradition of many thousands of years. We seldom know who first told any story (folktales for example). They were told orally, never written down. And every storyteller had his/her own unique way to tell it. They never concerned themselves with copyright issues. Our modern world insists that we do. Because today the end result of every creative endeavor is PROFIT. And we are made to believe that someone else profiting from our hard work is a crime. But for a moment if you take away ‘profit’ from the equation, the other big parameter left that we can earn is – SATISFACTION. And that can’t be stolen from us, by anybody. So what I might have lost in monetary terms, I more than made up by the satisfaction of being able to keep churning out stories consistently for almost a decade now.

Every time ‘copyright’ and ‘profit’ enters the storytelling discourse, I don’t have much to contribute in the matter.

- In this interview, I like the way you talk about imagination and films. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1ViW0qLvlo&feature=youtu.be&a Have you read the debut novel by David Duchony, Holy Cow and a collection of short stories by Bollywood actors called Faction? I think you may like it. Both of you share this common trait of being closely associated with the film world, but it has a tremendous impact on your scripts. There is a clarity in the simplicity with which you write, without dumbing down, but is very powerful.

Yes, it is the only reason I considered film as a medium to express myself through. I wasn’t a film buff growing up. As I’ve said in that IFFK interview I in fact had a problem with my ‘imagination’ not being allowed free rein while watching a film. Everything was imagined for me. It was stifling. Unlike reading a book, or listening to music, where my imagination took full flight. I considered film only because I wanted to do everything simultaneously – write, visualize, choreograph, create music, play with sound, perform, everything. And, to my dismay(!) I realized only this medium that I had reviled all these years would actually allow me that.

You are right about the cross-effect prose and film writing has if done simultaneously. Not only have I seen my prose writing become more visual – and hence less reliant on descriptors / adjectives / turns of phrase – but I’ve seen my screenwriting become less reliant on exposition through dialogue, because I find myself more able to express mood and a character’s inner processes through silent action. It’s a very personal epiphany, but it seems to be serving me well in both media.

I haven’t read Holy Cow or Faction but I will do so now.

Interestingly though I think I’ve learnt a lot from another medium – one that inhabits the space between prose and cinema – the graphic novel. Some American author-artists – David Mazzuchelli, Frank Miller; the Japanese socio-political manga master Yoshihiro Tatsumi; Craig Thompson; the French Marc-Antoine Mathieu – these are storytellers whose prose marries itself to the image to convey powerful ideas in a third form. They’re all master prose writers, but their visuals complement their prose, hence their prose is sparse. And since their prose does half the work, their images are powerful in the choices they make. Their work has gone some way in shaping my crossover journeys between film and prose, or vice-versa.

- Is it fair to ask how much has the film world influenced your writing?

I think I have in some way answered this question. My film-writing has affected my writing yes. But since even today I’m not a quintessential film buff, very little cinema has really ‘influenced’ me. To date I have a conflicted relationship with the watching of films. Because a film is so complete in its creating of the world, and I have absolutely nothing left to imagine / add on my own while ‘watching’ a film, I’m left feeling cheated every time I watch a film. Even if it is a film I love. So cinema doesn’t inspire me. I consume it sparely. I respect what it can help a storyteller achieve. But it almost never influences my choices.

Instead, art, poetry, music, real life experiences, love lost, death, inequality, conversation, comics, illustration, the look on people’s faces when they are eating, fucking, killing someone, being denied, discovering a devastating secret, the looks in animals’ eyes when they’re startled by the brutality of man – these are some of my influences.

- Will you try your hand at writing a novel?

Of course! I have to finish at least one before I die. I’m some way into it already. It is, once again, an adaptation of a screenplay I wrote 7-8 years ago, for a film that got partly shot, but might never see the light of day. On the surface of it it’s a story of three boys – one from Assam, one from Kashmir, one from Sitamarhi, Bihar (one of the earliest entry points into India for the Nepali Maoist ideology) – at times in the history of these regions when separatist movements are gaining momentum. Through their lives I seek to explore whether the nation-state we call India even deserves to be. Or are we better off as a collection of several small independent nation-states. It’s very experimental in form, jumping several first person perspectives as the story progresses and gradually explodes outwards. I don’t know yet when I’ll complete it. But I do want to. It’s the only other mission I have of my life. The first being to see my feature-length film release on cinema screens nation-wide. Don’t ask me why. I just do. I’ve tried too hard and waited too long to not want that very, very badly.

But if someone shows interest in my novel I’m willing to put everything else on hold to finish it first.

I guess everything’s a battle in some form or another. It’s about which one we choose to fight today, and which we leave for the days to come.

Devashish Makhija Forgetting HarperCollins Publishers India, Noida, 2014. Pb. pp. 240 Rs.350

1 March 2015

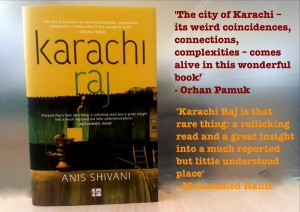

Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;

Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;