Interview with Aditya Iyengar

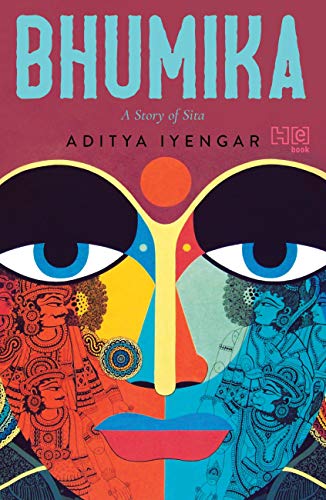

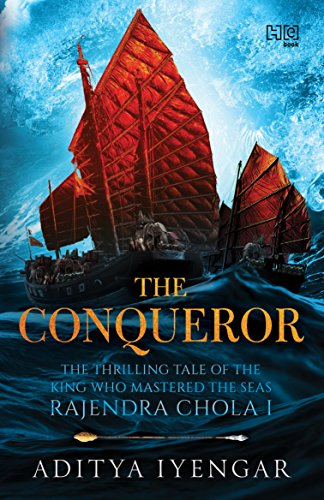

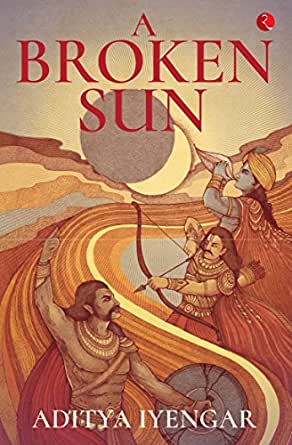

Retelling of Indian mythology by Indian novelists is proving to be quite an interesting exercise as it is allows the modern storyteller to choose and stress upon different aspects of the epics. Aditya Iyengar is one such writer. He writes Indian mythological and historical tales through the eyes of often unexplored and peripheral characters. His works include – The Thirteenth Day, Palace of Assassins, A Broken Sun, The Conqueror and Bhumika. His novel Bhumika was longlisted for the Mathrubhumi Book of the Year 2020. He lives in Mumbai.

- How did you get into professional writing?

I’ve always been a voracious reader. But I think somewhere in my mid-twenties, I decided I wanted to attempt to write a novel. I think the confidence came after reading Arun Kolatkar’s poetry and Kiran Nagarkar’s seminal Cuckold. Somehow these made me feel that I could express myself through the English language but in an Indian idiom in a manner that felt entirely natural.

I’ve always been fond of mythology, historical and science fiction, so I knew I wanted to attempt one of these genres. I don’t remember why I decided to write a mythological retelling over the other genres. Perhaps because the story I had for my first novel (The Thirteenth Day) was the clearest in my head. Anyway, it took me a few years to actually develop it into something resembling a coherent narrative.

I don’t write for a living. I have a day job that doesn’t involve creative writing (though creative writing as a skill comes in handy in virtually every trade). It’s a conscious call I’ve taken to take the pressure off my writing. Also, the writing life is a lonely one, and natural introverts like me would never meet people if they decided to stay at home and write all day.

2. What appeals to you in telling the kind of stories that you choose to tell? Stories that are based in myth?

I’m a huge fan of mythological retellings and historical fiction. The past, whether it’s historical or epic, is strange and exciting territory There’s something about reading about characters from the past or from epic fiction and feeling a human kinship with them. In a way it reminds one that we are all connected, and through the years have had the same motivations.

3. How did you develop a passion for mythology? Are there any favourite retellings of the mythological tales that appeal to you?

Growing up, I was very fascinated by historical and mythological stories. I’m not sure why. I’ve certainly never analysed it. Some kids are interested in sports, some find science projects fun – I just really enjoyed reading history and mythology. My childhood fascination for the past (both historical and epic), I think, came out through my novels. Some of my favourite mythological retellings have been K.M. Munshi’s wonderful Krishnavatara, C Rajagopalachari and Kamala Subramaniam’s retellings of the Mahabharata, and Colleen McCullough’s The Song of Troy (which is based on the Illiad).

4. How do you plan your novels?

I used to be a rigorous planner. I made notes for chapters, listed out characters, motivations, and tried to find what Vince Gilligan, the head writer of Breaking Bad calls “where the character’s head is at”.

I’ve written five novels. My preparatory notes have reduced for each novel to the point that I wrote Bhumika with only a broad story in mind, and no chapter-wise road map.

I’ve come to the conclusion that every novel requires a different process of planning. But if you have a broad story in your head, the details can be worked out as you write the novel. One doesn’t necessarily need to work out details before they start the novel, though it can be helpful even if one does.

5. What is your daily discipline to write?

I don’t write every day. I only write when I’m working on a project. Mostly, I get up early, work on my book for a little while, then head for work. Sometimes, I come back from the office and work for a bit too. On weekends, I wake up early and work till about 5 pm, after which I turn off my laptop.

I sit on a rocking chair, and balance my laptop on my lap and type. I don’t eat or drink anything except at meal times, and I end up eating very little if I’m absorbed in my work. I don’t read or watch anything on the telly during these times too. It’s a fairly hermit-like existence. Write, Go to Office, Return, Eat, Sleep and Repeat. Of course, such a lifestyle is unsustainable, so I normally write and finish novels within a few months. I have a healthy respect for deadlines, so I set myself a schedule and try hard to stick to it.

6. How much research does a book entail?

The level of research really depends on the novel. For my historical fiction novel – The Conqueror, I needed to read up on the Chola kingdom and the Srivijaya empire in Indonesia. I read a number of books and many academic papers and articles before I began writing the novel. A lot of my research was also shaped by the elements I wanted to include in the novel – for example, I wanted to write about one of the characters getting heavily drunk so I did research on the kinds of liquors that were available in those times.

For my Mahabharata and Ramayana novels, the research is limited since I already know most of the events through childhood retellings (Thanks, Mom!). Though I have also read some incredible translations that have helped shape my perspective. My mytho-fantasy series on Ashwatthama starts after the events of the Mahabharata and is entirely fictional.

7. What has changed in your writing style from the first book to the present one?

I’d like to believe my style is now more compact. I can express myself with fewer words. Also, I’m more confident using the full toolkit of punctuation marks. When I began, I would only use full-stops and abhorred any use of exclamation marks or colons and semi-colons. While I’m still very, very judicious about how I sprinkle those exclamations, I’ve learned how they can be used appropriately, for maximum effect.

8. Are there any particular darlings in your writing that you have had to kill off knowing it is for the good of the manuscript? Does it hurt to take these decisions?

Oh no, I absolutely couldn’t kill any of my darlings. Take some meat off them, yes – but what is the point of writing for pleasure if you have to kill your darlings?

9. Why create Bhumika in the way you did when the trend seems to be to retell stories in the way we have inherited the narratives?

I think our ideas of the purity of inherited narratives are not accurate. There have been several retellings and re-interpretations of the epics over the years and across different regions all over the country. I’d like to believe I’m following in a grand tradition of re-interpreting stories to make them more contemporary, like so many writers better than me have done before.

10. When do you find the time to read?

I don’t really read anymore. Not like I used to at any rate. I’m currently plodding through Richard Eaton’s A Social History of The Deccan, which is a tragedy because it is such a lovely book that I would finish it in a few days under normal circumstances. These days, between the job and daily chores, I find all my time going in the business of the day. I try reading in snatches of time – before going to bed or after finishing my work or before breakfast – and hastily devour as much of the book as possible. It’s almost become like having a clandestine lover. You meet with great difficulty, away from the eyes of the world, and cherish every moment together.

11. How many more novels have you drafted?

I’ve written a novel set in the film industry – it’s a dark comedy, but it’s languishing on my desktop because I haven’t had the time to do a FINAL FINAL.doc edit. Other than that, I have a few ideas for novels (two historical and one mythological) that I have yet to begin working on.

23 April 2020

An interview with writer, publisher and anthologist, David Davidar regarding his new book, A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. It is a collection of 39 short stories by Indian writers. It consists of translations and those written originally in English and has been published by Aleph Book

An interview with writer, publisher and anthologist, David Davidar regarding his new book, A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. It is a collection of 39 short stories by Indian writers. It consists of translations and those written originally in English and has been published by Aleph Book  Company. This episode of Kitaabnama was recorded on 10 April 2015.

Company. This episode of Kitaabnama was recorded on 10 April 2015.