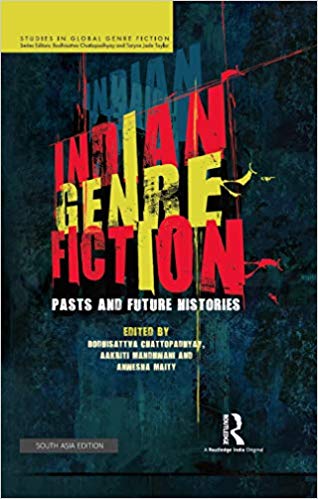

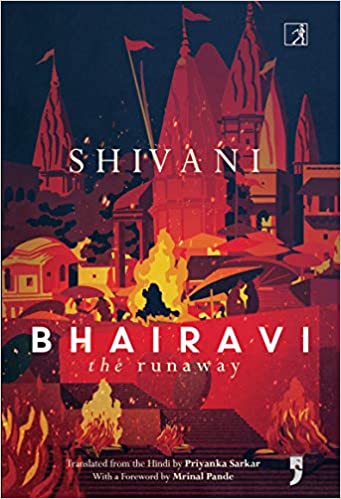

Shivani’s “Bhairavi: The Runaway”

The well-known Hindi writer, Shivani aka Gaura Pant was enormously popular. She was fluent in four languages — Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati and English. She also knew Sanskrit. According to her daughter, the noted journalist, Mrinal Pande, Shivani wrote her first story in Bengali but was dissauaded to do so by Rabindranath Tagore, who advised her to write in her own tongue. So she became a Hindi writer.

Many who grew up reading Hindi literature have stories to share about how generations of folks would wait for the next story to be published by Shivani. Grandmothers would encourage their granddaughters to read Shivani’s stories too. But as her daughter, the noted translator and writer, Ira Pande points out, “she wrote novels and stories that had strong women characters who rebelled against all such values and social inequalities. This also accounted for her lifelong fascination with those who lived on the margins—mendicants, lunatics and lepers. Time and again, she returns in her short stories and novels to characters drawn from those to whom rigid social values cannot be applied.” ( “A Conservative Rebel: An Unusual Mother ” by Ira Pande, Manushi, No 147 or read Ira Pande’s excellent book on her mother — Diddi: My Mother’s Voice ) . Nevertheless, by all accounts, Shivani’s readers were not confined to a particular gender. Everyone read her. Everyone enjoyed reading her stories. She seems to have been the Indian equivalent of Charles Dickens in her popularity and her readers shared the same sense of excitement for her next story as Victorian readers did for the next instalment of a Dickension story.

So when Simon & Schuster India announced the publication of an English translation of Shivani’s Bhairavi: The Runaway, it caused a ripple of excitement. Priyanka Sarkar is an accomplished translator and an editor and her awe at being entrusted with a novel by Shivani shines through her prefatory remarks. The foreword has been written by Mrinal Pande who observes that “As her [Shivani] reader and daughter, I meet her countless admirers all over the globe. Among them are simple housewives and professional men and women, school kids, and a surprisingly large number of diaspora Indians from India’s Hindi belt, who confess they developed a taste for Hindi after reading Shivani’s books. All of them confide how their mother, or grandmother or even great grandmother had first introduced them to Shivani’s writings and once into it they were hooked for life.”

She adds,

Women writers who have this sort of strange freedom thrust on them, mostly resolve their tensions in laughter and in prose and in doing so they will, almost inadvertantly, confer the gift of free thinking on their daughters. I learnt from Shivani both as mother and reader, that women leading socially secure lives as mother and wives are not morally more credible or more capable than those who are without family or child. Till the end, Shivani remained a kaleidoscopic character for me: outwardly traditional but bold, perverse, un-beholden and totally free when she puts pen to paper. Reading Bhairavi and the strange composure and compassion in these pages that co-exists with pain and hurt, I feel it is not the moralist’s why, but a humane what, that the writer ekes out from life, holds tenderly and finally redeems from oblivion.

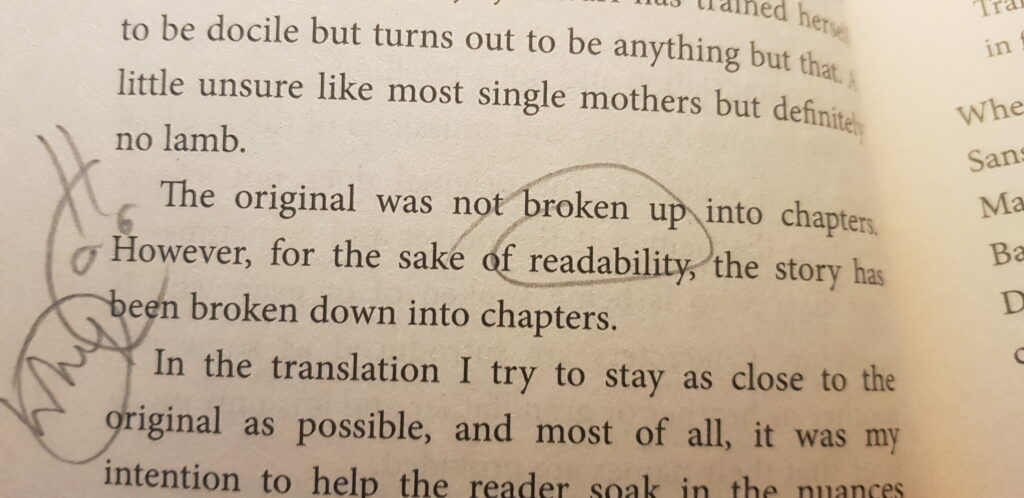

With the formidable combination of a tremendous writer and of a talented translator, I was looking forward to reading a fine translation of Bhairavi. Instead I was confounded and deeply saddened by what I encountered. Apparently the original novel is written in continuation and slipping in and out of the languages Shivani knew. Of course it is a challenging task to translate such a text for the modern reader but to say “for the sake of readability, the story has been broken down into chapters” was astonishing. I have still been unable to wrap my head around this fact that how can one take such liberty with a piece of work that is already recognised for its craftsmanship. Translated works are known to have been experimental in their literary form such as run on sentences or no chapters but the translators have never taken the liberty of chopping up the original text. Take for instance award-winning writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai who is known for his extraordinarly long and immersive sentences. The English translations of his text are never cut up for the sake of the convenience of the modern reader. And yet, he has won some major prizes such as the International Booker Prize. In fact with Bhairavi too, if the reader chooses to ignore the chapter breaks and goes into a sort of creative sleep and reads the text smoothly, then one gets a sense of rhythm and sense of what Shivani probably conveys in the original text. But if the reader makes the mistake of allowing the present form of the English text to govern one’s reading, it does not work.

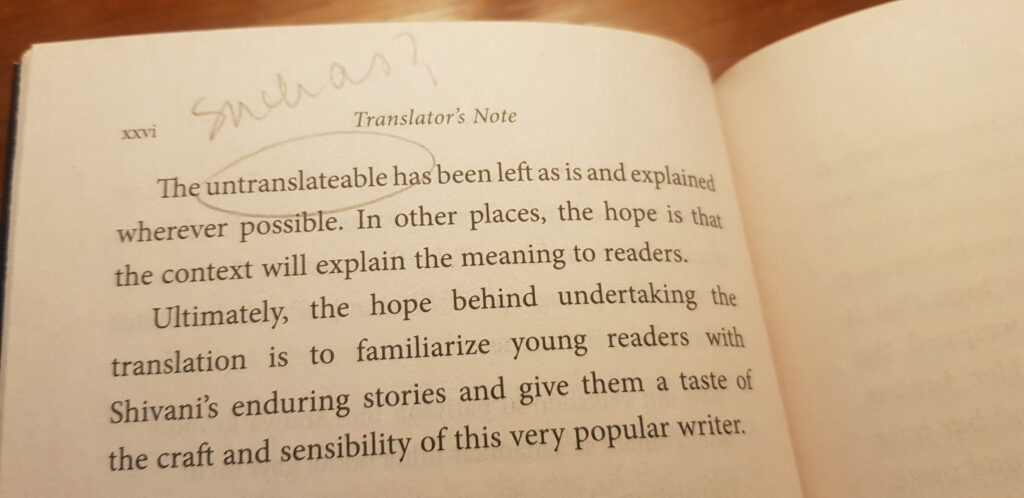

The second remark that I came upon and troubled me greatly was “the untranslateable has been left as is and explained wherever possible”. This comment did not make any sense to me especially since I had recently interviewed the acclaimed translator Anthony Shugaar who is known for his numerous translations of French and Italian texts into English. In fact, he makes precisely this very point “there are no untranslatable words, there are untranslatable worlds. My job is to build bridges from them to where we live” ( “Loss, Betrayal, and Inaccuracy: A Translator’s Handbook”, VQR, 19 Feb 2014).

Despite reading this remark in the Translator’s note in Bhairavi , I proceeded ahead with the novel. Alas, it become a tougher and tougher task to do so. In my humble opinion, if Shivani chose to play with multiple languages to write her novel in, then the least the translator could do is to acknowledge this craftsmanship and understand the cultural context. Perhaps the best way to create a translation in the destination language is to imbue it with the cultural context, much in the way Anthony Shugaar seems to create. Translation is not merely an act of linguistic conversion. If it was only that we could rely upon neural technology and use digital tools such as Google Translate. Somewhere the distinction has to creep in between manmade and computer translations.

Having said that I look forward to the next work of translation Priyanka Sarkar does. She is definitely a translator with potential and we need more translators like her to make our rich cultural heritage visible to a larger audience.

23 Oct 2020