“Milkman” by Anna Burns

Man Booker Prize winner 2018 Anna Burn’s novel Milkman is about a nameless eighteen-year-old narrator, most often referred to as the “reading-while-walking” girl who prefers to read nineteenth rather than twentieth century literature because she does not like the twentieth century. Milkman is set in a nameless Irish city —-p robably Belfast just as the era is never confirmed. It is about the city caught in the battles between the IRA, the Renouncers and the British Army possibly during the 1970s judging by the clues peppered throughout the story. It is about the girl observing and commenting upon her neighbourhood. Unfortunately she begins to be stalked by the forty-one-year-old “Milkman” — not the real one. ( The IRA delivered petrol bombs in milk crates. ) Then to her dismay tongues begin to wag and even her mother is not willing to believe her — that there is no truth in the rumours being circulated. Immediately after winning the prize Anna Burns was quoted as saying “Although it is recognisable as this skewed form of Belfast, it’s not really Belfast in the 70s. I would like to think it could be seen as any sort of totalitarian, closed society existing in similarly oppressive conditions … I see it as a fiction about an entire society living under extreme pressure, with longterm violence seen as the norm.”

Man Booker Prize winner 2018 Anna Burn’s novel Milkman is about a nameless eighteen-year-old narrator, most often referred to as the “reading-while-walking” girl who prefers to read nineteenth rather than twentieth century literature because she does not like the twentieth century. Milkman is set in a nameless Irish city —-p robably Belfast just as the era is never confirmed. It is about the city caught in the battles between the IRA, the Renouncers and the British Army possibly during the 1970s judging by the clues peppered throughout the story. It is about the girl observing and commenting upon her neighbourhood. Unfortunately she begins to be stalked by the forty-one-year-old “Milkman” — not the real one. ( The IRA delivered petrol bombs in milk crates. ) Then to her dismay tongues begin to wag and even her mother is not willing to believe her — that there is no truth in the rumours being circulated. Immediately after winning the prize Anna Burns was quoted as saying “Although it is recognisable as this skewed form of Belfast, it’s not really Belfast in the 70s. I would like to think it could be seen as any sort of totalitarian, closed society existing in similarly oppressive conditions … I see it as a fiction about an entire society living under extreme pressure, with longterm violence seen as the norm.”

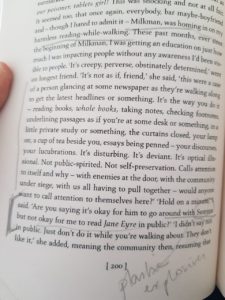

Milkman was many years in the making and is the stuff literary legends are made of. The fifty-six-year-old Anna  Burns acknowledging the fairy tale Booker win said “‘It’s nice to feel I’m solvent. That’s a huge gift’” It is an extraordinary novel for very early on in the story it is as if the reader is an invisible companion to the narrator observing the proceedings with insights into how they think. There are large portions of the narrative that are running text, a single paragraph that runs across pages, which at first may seem daunting to read but is not so. Very often Milkman is being referred to as being Beckettian but Anna Burns clarifies in her interviews that she only read Samuel Beckett once her novel had been written. Whereas in fact it would be worthwhile to notice how the form of her prose, the fluidity of it, the mildly digressing style while observing and reporting incidents dispassionately, and at other times conveying neighbourhood gossip and events as is, in a detached dead pan manner, without any analysis is ultimately a very womanly quality.

Burns acknowledging the fairy tale Booker win said “‘It’s nice to feel I’m solvent. That’s a huge gift’” It is an extraordinary novel for very early on in the story it is as if the reader is an invisible companion to the narrator observing the proceedings with insights into how they think. There are large portions of the narrative that are running text, a single paragraph that runs across pages, which at first may seem daunting to read but is not so. Very often Milkman is being referred to as being Beckettian but Anna Burns clarifies in her interviews that she only read Samuel Beckett once her novel had been written. Whereas in fact it would be worthwhile to notice how the form of her prose, the fluidity of it, the mildly digressing style while observing and reporting incidents dispassionately, and at other times conveying neighbourhood gossip and events as is, in a detached dead pan manner, without any analysis is ultimately a very womanly quality.

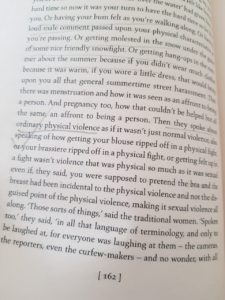

Milkman is much like the commentary many women inevitably internalise. The novel merely makes visible that which is mostly kept out of public spaces for women as it would be mostly perceived as idle chatter. It is also remarkable how effectively Anna Burns portrays a reading-while-walking girl who is in all likelihood absorbed in her book but is also able to observe the landscape and people around her as she walks past.  There is violence which she acknowledges in many interviews post-Booker win were because of the Ireland she grew up in. There is a particularly horrific and violent scene involving the butchering of dogs and left in a pile. In The New Statesman interview she says:

There is violence which she acknowledges in many interviews post-Booker win were because of the Ireland she grew up in. There is a particularly horrific and violent scene involving the butchering of dogs and left in a pile. In The New Statesman interview she says:

… I remember seeing that as a child. It was down the bottom of our street. I was seven or eight, so I don’t really know how high the pile was, but it did look like a mound of dead dogs, with their throats cut – I couldn’t see any heads, so I thought all their heads were missing. It was one of those images that stay with you.

The remarkable effect Milkman has upon its readers is for its relevance to the #MeToo movement is purely coincidental as Anna Burns has reiterated this novel was completed in 2014, well before the movement began. At the same its powerful impact is for its visibilisation of the silences most women are trained to inculcate. Most often women across cultures are socially conditioned to keep their opinions to themselves and conform to what is expected of them. Also their word is very likely dismissed especially when it involves as in the case of a creepy, older man, a stalker, who also happens to belong to the IRA. So the young narrator gets pushed more and more into a corner with everyone including her mother disbelieving her about the false rumours being circulated about her and the milkman. Also by resorting to use the interior monologue style of writing for most part of the novel Anna Burns makes the reader privy to the innermost thoughts of the girl thereby stripping away any pretence the narrator may “normally” have adopted in real life.

There are so many portions in the story that will resonate with women readers while being revelatory to male readers. As novelist Idra Novey points out in her Paris Review essay “The Silence of Sexual Assault in Literature” ( 4 Oct 2018) it is the silences that are critical in literature — what is glossed over and that which is hidden from view.

Though the story [Flannery O’Connor’s story “Good Country People”] was published over sixty years ago, the sick abuse of power is disturbingly similar to any number of testimonies that have emerged this past year. O’Connor artfully elides what exactly the Bible salesman does, or doesn’t do, to Hulga in the barn. That elision evokes the roaring silence that she will now endure, returning to this horrifying experience within the solitude of her mind.

It is exactly this silencing of the women that has remained quietly hidden away from the “public” view —- a view that has been mostly defined by patriarchal codes of conduct. Although these sorts of conversations, thoughts and ideas being expressed freely now in literature are and have always been familiar to women.

Milkman is a powerful book that begs to be read widely.

To buy the Milkman on Amazon India:

26 Oct 2018