Celebrating the bicentenary of Charles Baudelaire

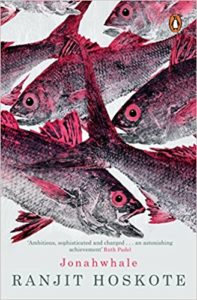

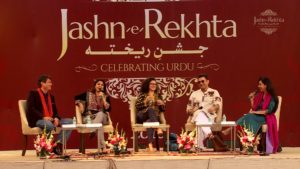

On 9 April 2021, I was invited by the French Institute in India to moderate a panel discussion on Charles Baudelaire. It was to celebrate the French poet, essayist and translator’s bicentenary. His dates are 1821 – 1867. It was a daunting task as the panelists included poets/writers such as Jeet Thayil, Amrita Narayanan, Ranjit Hoskote and Anupama Raju. Nevertheless the conversation went off beautifully. It was almost magical. Here is the link to the recording. It is available on the French Institute of India’s Facebook page. Take a look:

https://www.facebook.com/IFInde/videos/762611194439425

In anticipation of the event, I had prepared a bunch of questions to pose to the panellists. Fortunately, the need never arose since many of the points were addressed in the individual speeches everyone gave. Anyhow, I am posting the list of questions here as well:

- Love is a significant portion of Baudelaire’s poetry. Would you say that it is a crucial element in your own writings? If yes, what is the ideal form of treating love as a subject in poetry, assuming that there is an “ideal” notion to be achieved.

2. There is a very modern quality to Baudelaire’s essays and poems especially in his emphasis on the present. It permeates the style of his writing and the vocabulary he chooses. It is not what you expect in nineteenth century literature, especially French literature, with its emphasis on the formal. Would you say that this “modern” tenor is to be emulated and if yes, is it harder to do so than it seems? (Of course, I can only access his works in translation.)

3. In his essay on “The Universal Exhibition of 1835”, he asks, “What are the laws that determine this shifting of artistic vitality?” It seems to be a question that he ponders over even in his poetry. What do you think? Are there any such laws governing “artistic vitality”?

4. For a poet, how important is the imagination and how important is it to remain alive to events, stories, people etc? These could be contemporary or historical.

5. Role of a poet/critic as a social commentator? Is it essential to communicate with readers in the language that they will understand and appreciate or deign to create flowery poetry?

6. What is the function of a critic? What should be the nature of his/her criticism? Is this reflected in your poetry and prose?

7. Playing with form comes naturally to Baudelaire, as it seems to all of you. Is it a natural progression for a poet to prose or are there a different set of rules governing each form? Are rules meant to be broken as exhibited by Baudelaire?

8. Does art have to be useful or can it focus upon being aesthetically pleasing?

9. What is the responsibility of the poet/writer in defining the cultural landscape? Or do they only create for themselves solely?

10. What is the purpose of art? Is to create beauty, pursue truths? Be concerned with the ethics of goodness and morality?

11. For Baudelaire, a work of art was measured by the impact it had upon its subject rather than how it conformed to objective standards of proportion. Do you agree with this statement vis-à-vis your own works and its impact upon readers?

12. Baudelaire believed that the poet and critic within him are inseparable. Would you agree with the statement while analysing your own body of work?

13. Do you think technology has in anyway impacted the speed of movement and execution it imposes upon the artist? It is a conundrum that Baudelaire addresses in his essay, “The Painter of Modern Life” where he advocates time is spent fruitfully in creating something of beauty as it will make it more valuable. Yet, external factors do not necessarily permit this to happen. This was in the nineteenth century when technological advancements such as the printing presses and mass production were happening at a very rapid pace. It is much like what we are witnessing today as well. Almost like a second Industrial Revolution, if you will. So has the speed of the Internet dissemination, affected your creativity?

14. Always Be A Poet, Even In Prose!

9 April 2021