David Duchovny, “Holy Cow”

…My editor told me if I add some sex, curses, and maybe some potty humour, this will sell better to my “audience”. I don’t know who my audience is. I want everybody to hear this story, but my editor says human adults won’t take a talking animal seriously…So she’s gonna market it as a kids’ book. Which is fine by me, I like kids, but then she says, “Adults are gonna read this book to their kids so you have to sprinkle little inside jokes along the way with some allusions to pop culture from the last thirty years so they don’t get too bored. …” ( p. 29)

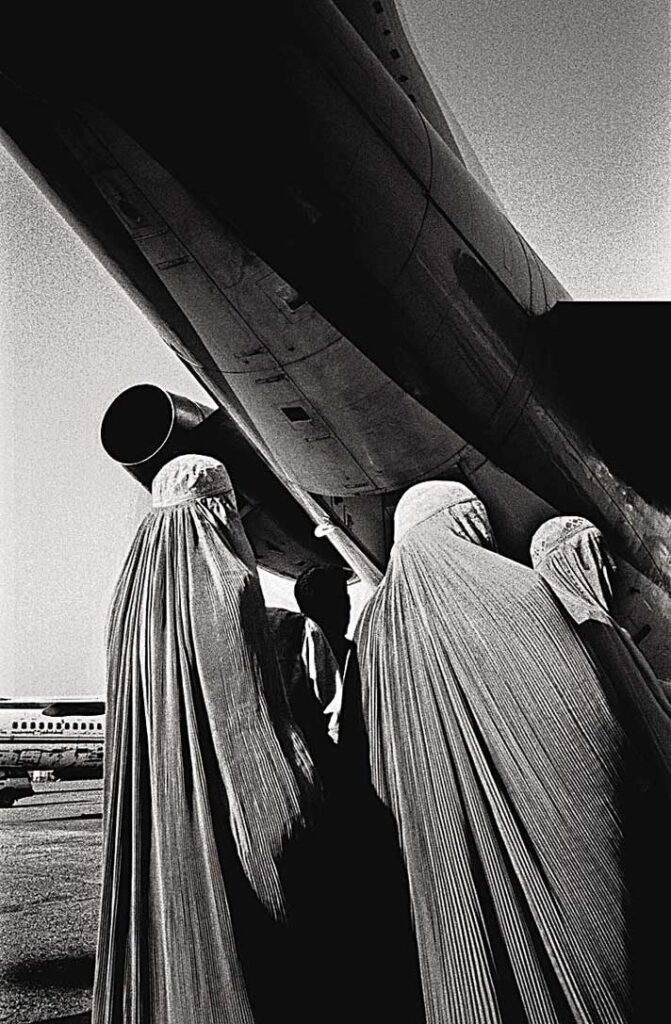

David Duchovny’s debut novel, Holy Cow, is about Elsie Bovary ( a cow), Shalom, formerly known as Jerry ( a pig who has converted to Judaism) and Tom ( a turkey). These anthropomorphic animals are living happily together on a farm, when for personal reasons they decide to escape. It is a memoir dictated by Elsie to her editor at a secret location. Elsie discovers that most cows end their lives in an abbatoir, so wants to go to India where cows are revered, Shalom is keen to visit Israel and Tom wants to go to Turkey. This motley group of friends manage to buy airline tickets online and go off on international travel. Along the way, Shalom manages to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict and is nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

…My editor told me if I add some sex, curses, and maybe some potty humour, this will sell better to my “audience”. I don’t know who my audience is. I want everybody to hear this story, but my editor says human adults won’t take a talking animal seriously…So she’s gonna market it as a kids’ book. Which is fine by me, I like kids, but then she says, “Adults are gonna read this book to their kids so you have to sprinkle little inside jokes along the way with some allusions to pop culture from the last thirty years so they don’t get too bored. …” ( p. 29)

David Duchovny’s debut novel, Holy Cow, is about Elsie Bovary ( a cow), Shalom, formerly known as Jerry ( a pig who has converted to Judaism) and Tom ( a turkey). These anthropomorphic animals are living happily together on a farm, when for personal reasons they decide to escape. It is a memoir dictated by Elsie to her editor at a secret location. Elsie discovers that most cows end their lives in an abbatoir, so wants to go to India where cows are revered, Shalom is keen to visit Israel and Tom wants to go to Turkey. This motley group of friends manage to buy airline tickets online and go off on international travel. Along the way, Shalom manages to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict and is nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

It took about twelve hours for Shalom and Tom to descend from the silly sky. But that’s the thing, you can’t just stay high. What goes up must come down. I had spent a long time dreaming of India, it’s true. But I’m not upset that India didn’t turn out the way I had planned, didn’t in the end match up with my dream India. Without my vision of a dream India, I never would have gone anywhere, never would have had any adventures at all. So I guess it’s not so important that dreams come true, it’s just important you have a dream to begin with, to get you to take your first steps. ( p.203)

According to David Duchovny, this story began as an idea for an animation film. He pitched it to Disney and Pixar, but it was rejected. This was ten years ago. Plus he was always keen to visit India. Finally he was persuaded by Jonathan Galassi, Farrar, Straus and Giroux to write it as a novel. David Duchovny studied English Literature at Princeton and Yale where he submitted a thesis on Beckett called “The Schizophrenic Critique of Pure Reason in Beckett’s Early Novels”. But as he said in his NYT interview, he likes fooling around with words. He likes language, “more Joycean, although that will sound really pretentious.”

Holy Cow may be a bildungsroman in the guise of a fable for children, but it really does not matter. It is a story that is smart. This is going to achieve cult status for its zaniness, sharp wit and intelligent irreverence with which it takes on “serious issues” such as religion, politics, conflict, animal slaughter, and vegetarian/vegan debates. The storytelling is pithy, with the dialogue moving at a crackling good pace. As David Duchovny said in an interview to Kirkus, “Years of acting had made me sensitive to dialogue.” The illustrations by Natalya Balnova are perfect. Read it.

Holy Cow novel, UK website: http://www.holycownovel.co.uk/

Elsie on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/HolyCowNovel

David Duchovny interviewed by Kirkus: https://www.kirkusreviews.com/tv/video/kirkus-tv-david-duchovny/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=image&utm_campaign=020315

Interviews in the New York Times ( 30 Jan 2015) : http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/01/magazine/david-duchovny-i-like-fooling-around-with-words.html?_r=0 and LA Times ( 30 Jan 2015): http://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-david-duchovny-20150201-story.html#page=1

Reviews from The Guardian ( 4 February 2015): http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/04/holy-cow-david-duchovny-review and Washington Post ( 3 February 2015): http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/actor-david-duchovnys-first-novel-holy-cow-is-a-madcap-fable-about-growing-up/2015/02/03/7638c694-a8b2-11e4-a06b-9df2002b86a0_story.html and Huffington Post ( 3 February 2015): http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/02/david-duchovny-book_n_6598702.html?ir=India

David Duchovny Holy Cow Headline, London, 2015.

5 February 2015