Literati – “The Critic” ( 19 July 2015)

My monthly column, Literati, in the Hindu Literary Review was published online ( 18 July 2015) and was in print ( 19 July 2015). Here is the http://www.thehindu.com/books/literary-review/jaya-bhattacharji-rose-on-the-world-of-books/article7429521.ece. I am also c&p the text below.

My monthly column, Literati, in the Hindu Literary Review was published online ( 18 July 2015) and was in print ( 19 July 2015). Here is the http://www.thehindu.com/books/literary-review/jaya-bhattacharji-rose-on-the-world-of-books/article7429521.ece. I am also c&p the text below.

In a column on January 11, 2015, The New York Times published Michiko Kakutani’s review of Harper Lee’s much-awaited Go Set A Watchman(@GSAWatchmanBook ) — on the front page, no less. There have been energetic nitpicking conversations about this review. But the truth is that any space given by a mainstream newspaper to a book review is unusual. For, despite the 50-year gap between To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set A Watchman, the latter has a two million print run. Lee’s resurrection of Atticus Finch has excited readers. According to Bloomberg, US, “it is the most pre-ordered book in her publisher’s history.” (July 9, 2015, http://bloom.bg/1HXxgij )

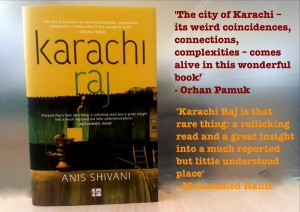

This pre-publication hype is any writer’s publicity dream. Space for reviewing books in print media is fast dwindling while rapidly gaining momentum on social media, prompting many writers to be creative in getting their books discovered. Popular writer, Ravi Subramanian has launched an app to help promote his books. Booksellers too have to be innovative — curating literary engagements or as the portly owner of Haji Suleiman and Sons tells Hafiz in Anis Shivani’s lengthy debut novel, Karachi Raj “Shelving is an art. Mixing the old and the new on the same subject is more important than getting the alphabetical order just right.”

An important part of the publishing ecosystem is the critic. The few well-read critics like James Wood, Amitava Kumar, Tim Parks and John Freeman are known and greatly valued for their honest, straightforward and informed observations. Whether in print or virtual space, by critics or others (publishing professionals use their Facebook walls to air frank opinions), a good review should generate conversation. Recently, Daniel Menaker — writer and former Editor-in-Chief, Random House Publishing Group — said of the new Harper Lee novel : “Here’s the thing: it is natural and inevitable for readers and experts to compare these two Harper Lee books to each other. But the comparisons have absolutely nothing to do with the quality of each book. They are two different objects. You can get historical perspective about an artist by comparing an early landscape to a late one, but the value of both remains entirely independent of their relation to each other. Rembrandt’s series of self-portraits is an excellent source of historical, biographical comparison, but as works of art they must be judged on their own merits. [Alexander] Alter’s piece in The Times is where it should be — outside the review arena. Kakutani’s “review” should have given no more than a nod to TKAM in discussing GSAW, if you ask me. The rest of the review would have been actually more useful if it had addressed the merits and problems with GSAW on its own terms. Seems to me.” (Quote reproduced with permission.)

With this, Menakar sparked off a crackling literary conversation about the merits of reviewing. To be a professional critic is never painless. It is particularly tough when the critic is an integral part of the literary set of concerned editors, publishers and authors; some of whom have acquired demi-god status. Thus Shamsar Rahman Faruqui’s The Mirror of Beauty and The Sun that Rose from the Earth, and Amitav Ghosh’s Flood of Fire, which are rich longwinded tapestries of the past, have had reasonably good sales and glowing critical acclaim. In his Afterword to Mantonama, Saadat Hasan Manto declares: “know-it-all pundits” can have a powerful impact on an author, but solace lies in realising that “literature…is a self-existent entity. …Literature is as alive and exuberant today as it was before it was discovered.” (My Name is Radha: The Essential Manto, translated by Muhammad Umar Memon.)

In ‘Bad News’, an essay in his splendid book, Lunch with a Bigot, Amitava Kumar sums it: “With all their beauty and artifice, novels often hide the ordinary grit of reality. …It is the irrepressible bubbling-up of the everyday, not the unbending demand of a rigid aesthetic, that makes a novel satisfying, that connects it to life.” Saikat Mazumdar’s exquisite The Firebird and K. R. Meera’s disturbing novella And Slowly Forgetting that Tree (translated from Malayalam by J. Devika) are fine examples of such satisfying literature.

15 August 2015

Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;

Anis Shivani has been a writer for many years. He is known as a short story writer and a poet. Karachi Raj is his debut novel. It was nearly ten years in the making. It is about a group of people across social classes who meet. Their lives get intertwined in a manner that is not easily expected in a very class conscious society existing in Pakistan today. Anis Shivani is a critic too. An example of his literary criticism is this splendid three-part essay he wrote for Huffington Post on contemporary American Literature. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/anis-shivani/we-are-all-neoliberals-no_b_7546606.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in ;