Comeback heroes, 28 September 2014

( In today’s edition of the Hindu Magazine, I have an article on the resurrection of literary characters by contemporary novelists. The link was published digitally on 27 September 2014. Here is the link: http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/comeback-heroes/article6452453.ece . It was carried in print as the lead article of the magazine on Sunday, 28 September 2014. I am also c&p the article below.)

With the release of Sophie Hannah’s The Monogram Murders earlier this month, Hercule Poirot comes back to life. This new mystery introduces a new character, Inspector Catchpool, who uses the first-person narrative style, similar to that of Dr. Watson. The novel was announced in October 2013 at the Frankfurt Book Fair in the presence of Agatha Christie’s grandson. This is only one in a line of novels written by contemporary novelists resurrecting literary characters. Usually these are characters that have remained popular over time.

With the release of Sophie Hannah’s The Monogram Murders earlier this month, Hercule Poirot comes back to life. This new mystery introduces a new character, Inspector Catchpool, who uses the first-person narrative style, similar to that of Dr. Watson. The novel was announced in October 2013 at the Frankfurt Book Fair in the presence of Agatha Christie’s grandson. This is only one in a line of novels written by contemporary novelists resurrecting literary characters. Usually these are characters that have remained popular over time.

Such revivals have been a tradition from the early 20th century. There were several Holmes stories in the

1910s and 1920s. But these were not very well known. Bulldog Drummond by Sapper was, perhaps, the first instance of a popular character being continued. The series was continued by Gerard Fairlie. Other bestseller series included Sudden (a series of westerns), which was continued after the author Oliver Strange’s death.

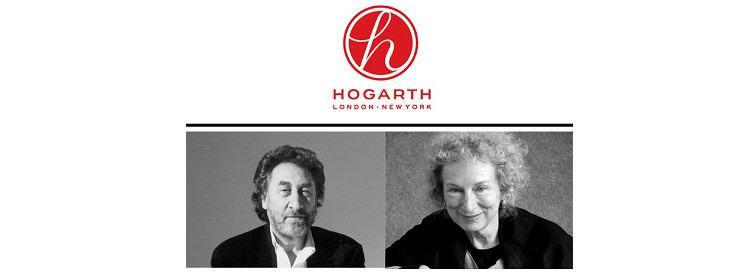

There are also lateral continuations — not with the characters as protagonists but spin-offs like P.D. James’ Death Comes to Pemberley,  Charlie Higson’s Young Bond series, Gregory Maguire’s The Wicked Years series, Anthony Read’s Baker Street Boys series and Andrew Lane’s Young Sherlock Holmes series.Vintage’ Hogarth Shakespeare imprint will soon present retellings of the Bard’s works for contemporary readers by some of today’s best-known international writers. October 2015 will

Charlie Higson’s Young Bond series, Gregory Maguire’s The Wicked Years series, Anthony Read’s Baker Street Boys series and Andrew Lane’s Young Sherlock Holmes series.Vintage’ Hogarth Shakespeare imprint will soon present retellings of the Bard’s works for contemporary readers by some of today’s best-known international writers. October 2015 will see the launch of Jeanette Winterson’s retelling of The Winter’s Tale and Howard Jacobson’s retelling of The Merchant of Venice will be out in February 2016, ahead of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in April 2016. The illustrious list includes Margaret Atwood (The Tempest), Tracy Chevalier (Othello), Gillian Flynn (Hamlet), Jo Nesbo (Macbeth) and Anne Tyler (The Taming of the Shrew). The series will be published in 12 languages across 18 territories.

see the launch of Jeanette Winterson’s retelling of The Winter’s Tale and Howard Jacobson’s retelling of The Merchant of Venice will be out in February 2016, ahead of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in April 2016. The illustrious list includes Margaret Atwood (The Tempest), Tracy Chevalier (Othello), Gillian Flynn (Hamlet), Jo Nesbo (Macbeth) and Anne Tyler (The Taming of the Shrew). The series will be published in 12 languages across 18 territories.

There are many reasons why these new stories strike a chord with modern readers. First is, of course, nostalgia and familiarity. Given the huge fan base of these characters, the new books have a relatively ready market but sometimes they are reinvented to find a

new readership. Mahmood Farooqui of Dastangoi says, “I think it is a good tactic to take up texts that are already familiar to some in the audience. Listening to a story and reading one are very different experiences.”

India sells more traditional bestsellers, says Thomas Abraham, Managing Director,  Hachette India. Like “Enid Blyton or Christie or Conan Doyle. So, yes, these will have a good market here. But the new revivals will sell much more in the west in year one at least because they are major literary events.” Caroline Newbury, VP, Marketing and Corporate Communications, Penguin Random House, points out that books like Solo and Jeeves and the Wedding Bells “have been successful across the globe, hitting bestseller lists in the U.K. and in places like Australia.”

Hachette India. Like “Enid Blyton or Christie or Conan Doyle. So, yes, these will have a good market here. But the new revivals will sell much more in the west in year one at least because they are major literary events.” Caroline Newbury, VP, Marketing and Corporate Communications, Penguin Random House, points out that books like Solo and Jeeves and the Wedding Bells “have been successful across the globe, hitting bestseller lists in the U.K. and in places like Australia.”

Kushalrani Gulab, a voracious reader, cannot resist these new novels. She is “driven by curiosity and the very, very small hope that, by some miracle, my beloved character and her/his world might actually come back from the dead. So far, there has been no miracle.” A sentiment that blogger Sheila Kumar echoes. “Truth to tell, I approach these tribute/resurrections with both reserve and caution.  Comparisons, while they are admittedly odious, are also inevitable in cases like these!” But, as Abraham points out, “You dislike them generally after having read them, so you contribute to the market anyway.”

Comparisons, while they are admittedly odious, are also inevitable in cases like these!” But, as Abraham points out, “You dislike them generally after having read them, so you contribute to the market anyway.”

An article in the Publisher’s Weekly describes Sophie Hannah as having “channelled” one of literature’s greats. But Gulab’s passionate response to this is: “I find it very hard to imagine that another author can do just as good a job as the original author… (who) knows her/his own character best because she/he has honed it over the years… Another author, however, only knows the character by a list of characteristics; from the outside, as a reader does. Not from the inside as the original author does. Also, characters tend to exist in a certain milieu. So unless the new author makes the characters contemporary, she/he has got to recreate the world around the character as well. That’s very hard to do when you haven’t actually lived in that time period.” In fact, Sophie Hannah says she found the names — Catchpool, Brignell, Negus, Sippell and Ducane — for most of her cast from tombstones as they had a “classic, old-fashioned feel about them”.

Yet these “continuations” raise the tricky question of copyright. Last year, the Conan Doyle Estate was “horrified that the ‘public domain’ might create multiple personalities of Sherlock Holmes” (September 2013). But in December 2013, a judge in the U.S. ruled that “Sherlock Holmes is definitely in the public domain”. The first story is bound by the original term of copyright. A new version does not extend the character’s copyright term for the estate. But copyright and permission to carry on the characters are two different things. So, if an estate has the legal right to stop any use of the character after the story’s copyright expires, may be they can. But they can’t stop the printing of existing works, if they have gone out of copyright.

Abraham refers to the attitude of Peter O’Donnell, creator of the Modesty Blaise series. “O’ Donnell told me that he wouldn’t like the idea of Modesty being carried on by someone else especially after the disastrous film version. That was one reason why he killed them off in Cobra Trap.” Attitudes vary hugely from estate to estate. As Newbury points out, Solo’s copyright lies with Ian Fleming Publications Ltd., whereas Jeeves and the Wedding Bells is attributed to Sebastian Faulks.

According to Rich Stim, Attorney, on the legal website, NOLO, “fictional characters can be protected separately from their underlying works as derivative copyrights, provided that they are sufficiently unique and distinctive like, James Bond, Fred Flintstone, Hannibal Lecter, and Snoopy. In Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp., Judge Learned Hand established the standard for character protection: “… the less developed the characters, the less they can be copyrighted; that is the penalty an author must bear for marking them too indistinctly.” Exploitation of fictional characters is a crucial source of revenue for entertainment and merchandising companies. Characters such as Superman and Mickey Mouse are the foundations of massive entertainment franchises and are commonly protected under both copyright and trademark law. Unfortunately the protection afforded to fictional characters sometimes clashes with the fair use right to comment upon or criticise those characters. ” ( http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/protecting-fictional-characters-under-copyright-law.html )

People will read the new versions, but if you ask them which character they want to see resurrected, the answer comes promptly: “none”. The truly worthy successor of a great mystery writer in the modern world, writing in English, in my humble opinion, is Anthony Horowitz. I am looking forward to his Moriarty to be released at the end of October.

Other literary revivals

James Bond: Colonel Sun by Kingsley Amis (as Robert Markham); Solo by William Boyd.

Sherlock Holmes: The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz and The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes by Jamyang Norbu, which also revived Hurree Babu from Rudyard Kipling’s Kim.

Bertie Wooster and Jeeves: Jeeves and the Wedding Bells by Sebastian Faulks.

Jason Bourne: The Bourne Imperative by Eric van Lustbader.

Famous Five: Sarah Bosse wrote 21 new novels with Enid Blyton’s characters in German.

In India, Dastango Mahmood Farooqui has resurrected Alice in Wonderland as Dastan Alice Ki, and has plans to adapt Gopi Gyne Bagha Byne and The Little Prince.

Update

The article has been corrected to reflect the following changes: Kingsley Amis wrote the Bond novels under the pen name of Robert Markham and not George Markham as was printed earlier. Secondly, the Moriarty novel by Anthony Horowitz will be available at the end of October and not at the end of this week as mentioned earlier.

28 September 2014