On “Consent” and “My Dark Vanessa”

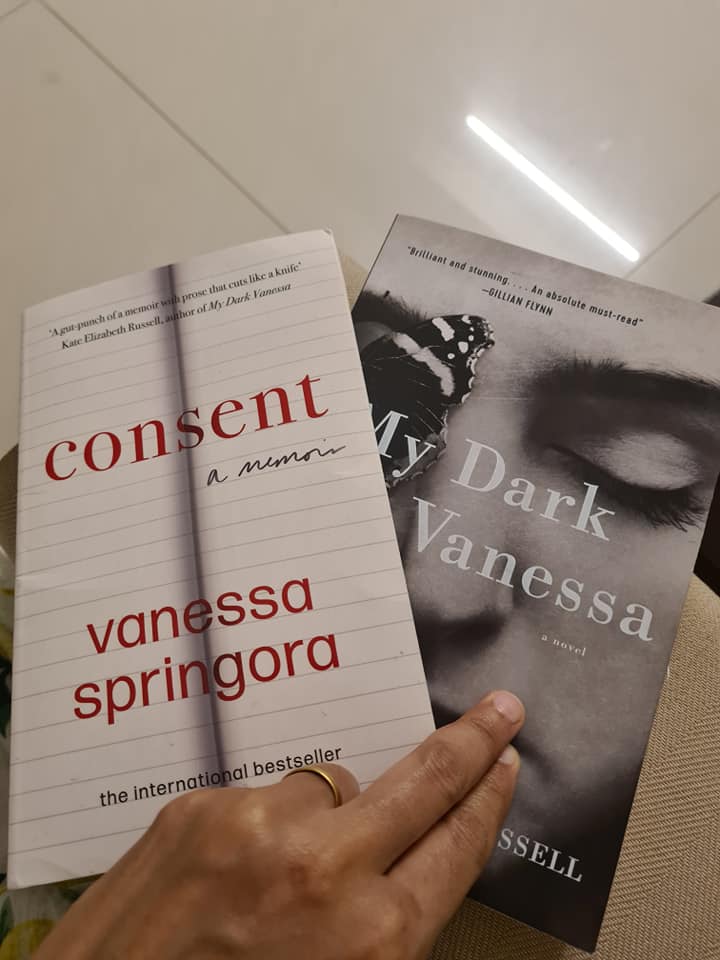

I read two books in quick succession — Consent and My Dark Vanessa ( HarperCollins). Both deal with the same subject. Grooming of a young school girl by a much older man, a writer / school teacher. The difference being that “Consent” is a true account by Vanessa Springora about her being groomed by French literary giant Gabriel Matzneff. It is a horrifying account of a 14-year-old girl groomed by a man who was at the time fifty years old. It is sickening. Springora, the head of the Julliard publishing house, met Matzneff at a dinner with her mother. ( https://www.theguardian.com/…/french-publishing-boss…) She was going through a troubled childhood as her parents were divorcing. Springora began a relationship with Matzneff but despite breaking it off two years later, she was not rid of the man for the next few decades. He pursued her. He stalked her. To the extent he wrote letters to her bosses in the publishing publishing she worked in. Ultimately, the Me Too movement happened, giving her the space to write her account of the events. Consent has been translated by Natasha Lehrer.

It is a memoir that flits between the perspective of the 14yo school girl and the 47yo Springora. It is disturbing. The school girl participates in the relationship with a much older man, but the adult Vanessa questions some of the acts/moments. She is able to see through the sexual exploitation and misogyny of the male writer and the protection he got from his social circle. It is incomprehensible to her. Consent is minimalistic. It does not delve into too many gory details but what the author chooses to share are emotionally shattering. It is inexplicable why this man was protected so well by the French establishment. If anyone had dared to look close enough, the evidence was apparent in the “illustrious” literary career where Matzneff published books that were thinly veiled accounts of his paedophilic acts, letters with his under-age mistresses and his regular visits to the Philippines to sexually exploit boys as young as eleven years old. Yet, Springora too only found the courage to reveal her dark secret after the Me Too movement became popular. She was relieved when she showed her mother this manuscript, who upon reading it said, “Don’t change a thing. This is your story.”

Towards the conclusion of the memoir, she writes:

I spent a long time thinking about the breach or confidentiality, particularly on a legal area that is otherwise strictly controlled, and I could only come up with one explanation. If it is illegal for an adult to have a sexual relationship with a minor who is under the age of fifteen, why is it tolerated when it is perpetrated by a representative of the artistic elite — a photographer, writer, filmmaker, or painter? It seems that an artist is of a separate caste, a being with superior virtues granted the ultimate authorization, in return for which he is required only to create an original and subversive piece of work. A sort of aristocrat in possession of exceptional privileges before whom we, in a state of blind stupefaction, suspend all judgement.

Were any other person to publish on social media a description of having sex with a child in the Philippines or brag about his collection of fourteen-year-old mistresses, he would find himself dealing with the police and be instantly considered a criminal.

Apart from artists, we have witnessed only Catholic priests being bestowed such a level of impunity.

Does literature really excuse everything?

It is a question that the reader is left asking with My Dark Vanessa. Nearly twenty years in the making and endorsed by Stephen King, it too explores the grooming of a young school girl by her English teacher. King calls it is a “hard story to read” and it is. Maybe because Kate Russell’s imagination is very detailed and sometimes gut-wrenching. It is torture to read this story. Initially I stopped reading it after a few pages but then managed to resume reading it after having finished reading Consent.

Somehow My Dark Vanessa comes across as a brilliantly crafted story but it is not as easy to read as Consent. Every despicable encounter/event in “Consent” is meticulously documented but it is shocking to read for the complicity of the French elite in permitting the writer to flourish. Not only did his books sell well, but he was lauded with honours, practically given an expense account by his publishers and the French state. It is astonishing. Whereas My Dark Vanessa reads like fiction although the events described in it are plausible. It is fiction but it sometimes seems to stem from an overactive imagination. The distinction is real. It is unsurprising that My Dark Vanessa has been shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize 2021.

Interestingly Vanessa Springora’s memoir Consent has been endorsed by Kate Elizabeth Russell, My Dark Vanessa, as “A gut-punch of a memoir with prose that cuts like a knife.”

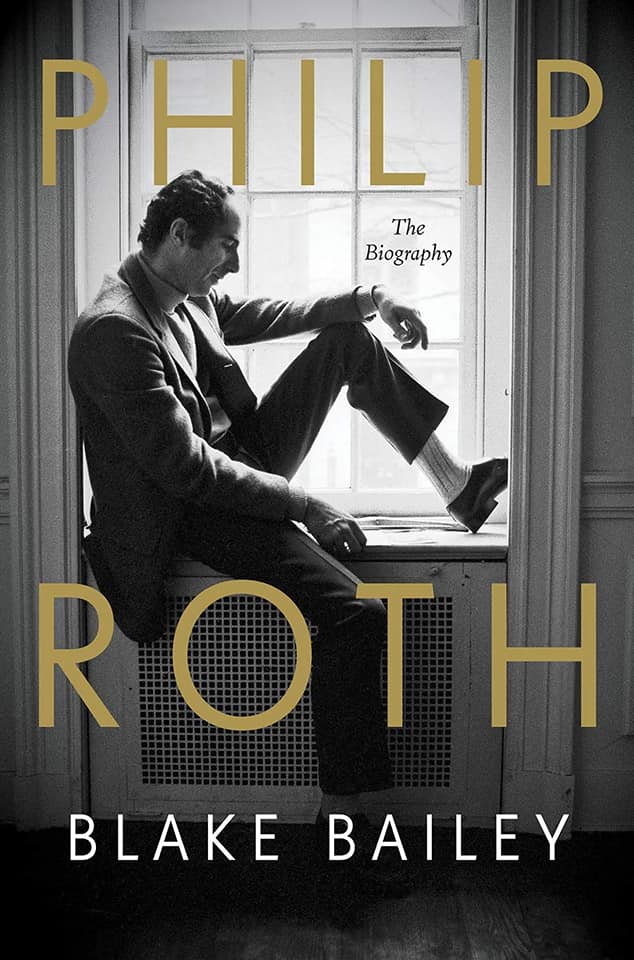

Currently the controversy about Blake Bailey, the biographer of Philip Roth, is raging in the world of Anglo-American publishing. Take for instance this article published in the Slate, called “Mr Bailey’s Class“. It eerily parallels the events described in My Dark Vanessa and Lisa Taddeo’s nonfiction Three Women, where the only girl who agreed to be identified by her real name was Maggie. She spoke about her grooming by her teacher and later taking him to court. It is hard at such moments to distinguish between what is real and what is fiction.

These kinds of stories are not going away in a hurry. There are many, many more. Predatory men and women exist. It is a fact. Children are vulnerable. These books may only focus upon young girls but there is no denying that boys too are victimised.There is no telling how much longer will these stories have to be constantly told for there to be some positive change in the attitude of individuals and society. But for now, read these stories.

2 May 2021