An extract from “The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta” by Kushanava Choudhury

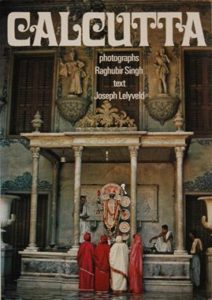

The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta by Kushanava Choudhury is a memoir of his time spent in Calcutta. It is the city of his parents and he has strong familial ties. Despite studying at Yale University he moves to Calcutta to join The Statesman as a reporter. After two years he quits and returns to do his doctorate from Princeton University. There are incredible descriptions recreating a city which is an odd mix of laid back, sometimes busy, always crowded, crumbling juxtaposed with the shiny new concrete jungles. The language is breathtakingly astonishing for in the tiny descriptions lie the multi-layered character of Calcutta. As William Dalrymple observes in the Guardian that The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta is “a beautifully observed and even more beautifully written new study of Calcutta”. All true. Yet it is impossible not to recall the late photographer Raghubir  Singh’s book Calcutta, a collection of photographs that sharply document details of a city where the old and new co-exist and continue to charm the outsider. Both the books by Kushanava Choudhury and Raghubir Singh are seminal for the way they capture an old but living city but with a foreigner’s perspective that is refreshing. For instance the following excerpt about little magazines and literary movements encapsulates the hyper-local while giving the global perspective.

Singh’s book Calcutta, a collection of photographs that sharply document details of a city where the old and new co-exist and continue to charm the outsider. Both the books by Kushanava Choudhury and Raghubir Singh are seminal for the way they capture an old but living city but with a foreigner’s perspective that is refreshing. For instance the following excerpt about little magazines and literary movements encapsulates the hyper-local while giving the global perspective.

The excerpt is taken from The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta by Kushanava Choudhury published with permission from the publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing India.

****

From Tamer Lane, along the gully that leads to the phantom urinal, there is a house with a mosaic mural of two birds with Bengali lettering. The letters read: ‘Little Magazine Library’.

Sandip Dutta sat in the front room of his family home. He looked a bit glum, half asleep, just like a Calcutta doctor in his chamber. Not one of those hotshot cardiologists who rake in millions, but more like the para homeopath without much business.

Surrounding him were bookshelves piled high with stacks of documents. Behind them was a glass showcase covered with pasted magazine clippings, like in a teenager’s room. They included cut-out pictures of Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Ingmar Bergman, Vincent Van Gogh, Jibanananda Das, Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, two big red lips, one big eye, Salvador Dalí and Che Guevara. A cartoon read, in rhyming Bengali: ‘Policeman, take off your helmet when you see a poet.’

On one wall was a taped computer printout: ‘‘‘I have been following the grim events (in Nandigram) and their consequences for the victims and am worried.” Noam Chomsky, Nov 13, 2007. 4:18:17 a.m. by email.’

Curios from local fairs were indiscriminately piled high on the desk. Cucumbers made of clay, pencils carved into nudes, tubes of cream that were actually pens, pens with craning rubber necks like swans, bronze statues from South Africa, masks from rural Bengal, a porcelain dancing girl from America. Behind them, Dutta looked like an alchemist in his lair.

‘I went to the National Library in 1971 and I saw that they were throwing away a bunch of little magazines,’ he said. ‘I had a little magazine of my own then, and I took it as a personal affront.’

No one was archiving little magazines at the time. No libraries kept them. When Dutta finished his masters, he started collecting them. At first he had a job that paid fifty rupees a month, then another for one hundred rupees, teaching three days a week in a remote rural school. ‘They were funny jobs,’ he said. ‘Jobs basically to buy magazines.’

In 1978, he got a teaching job down the road at City College School, he told me. That same year, in the two front rooms of his house, he began the Little Magazine Library. Since then he has been running this operation by himself – a bit like those heroes in Bollywood films who take on a whole band of ruffians single-handedly, he likes to say. His is a one-man effort to save the ephemeral present.

Every afternoon he came home from school and set to work at his library. A couple of days were devoted to maintenance, spraying to prevent bookworms and termites. The rest of the afternoons, he kept the library open to the public.

In Bengal, literary movements were usually connected to one little magazine or another. The heyday of the Bengali little magazine was probably the 1960s, when the poets Sunil, Shakti and Sandipan brought out Krittibas. No magazine today packs the same literary punch. Yet people keep publishing Bengali little magazines. By Sandip’s count, each year 500–600 little magazines are still published.

The little magazine originated in early-twentieth century America. Many of the radical strands of modernism – like James Joyce’s Ulysses, which was first serialised in the Chicago based Little Review – first appeared in little magazines before anyone bet on their viability in the capitalist market. The early works of T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, Zora Neale Hurston, Tennessee Williams, Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner and many others were all published in the little magazines of their day. Unlike regular magazines, they relied on patrons and modest sales rather than advertising. Shielded from market pressures, they provided a place for writers to be read, even if by a small number of people, and they gave intrepid readers a way to discover new writers. In Calcutta, like so many other aspects of life taken from the West – the tram, homeopathy, Communism – once adopted, little magazines then took on a life of their own and became central to how we understood ourselves. In a proper capitalist system, these magazines would have vanished long ago, taking with them thousands of writers. But like those 1950s Chevrolets in Havana, the Bengali little magazine rolls on, patched up, creaky, a source of local pride, as if it were uniquely ours and as integral to Bengali-ness as a fish curry and rice lunch.

***

Kushanava Choudhury The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta Trade Paperback | 272 pp | INR 499

21 August 2017