Sarvat Hasin, “This Wide Night”

They lived across the road from me for fifteen years without us ever having a conversation, something that seems impossible to me now. I’d built up the Malik sisters in my head before I really knew them. The combination of being at a boys’ school and Dada’s dislike for other people meant that these were the only real girls I ever saw. From the window in my bedroom, you could look through the trees and into their garden. I learned valuable things about the girls: how Maria played cards every evening with her mother, or that Ayesha always read and Bina sewed, and that the littlest, Leila liked to draw.

Jimmy lives with his paternal grandfather who is a prosperous export businessman. He is alone and spends a lot of his time watching the Malik house. The Malik family consists of four sisters- Maria, Bina, Leila and Ayesha/Ash . Their father is “a navy captain, whose name was on the silver plaque outside their gate, spent most of his time away from home”. Their mother Mehrunissa supervises the home and by all accounts is quite lenient in her daughters’ upbringing. It is never spelled out by Sarvat Hasin in her debut novel The Wide Night but there is a shift in dynamics from the freedoms available in a women-only home as compared to one in which there is a man’s presence. For instance when the Captain returns from the war – it is a challenging period of adjustment for both sexes:

How could her father come home to a place that did not feel like it belonged to him? The switch of energy during his visits, the house worked into a dark frenzy. It could only work in small bursts, the spikes of energy of reordered lives. There was no space for him in the larger sweep of their lives – how long could Ash keep wearing her dupatta over one shoulder and pinning back the tufts of her hair that escaped from their short nest. How many nights could Leila hold her tongue at the dinner table and bite it against her usual chatter of boys and money and pretty things. In her father’s presence she was washed out, a paler version of herself, hands folded in her lap and her voice only murmuring to ask for more roti, a glass of water. Even Bina was required to modify herself: fewer hours spent volunteering, and no more bringing her stitching into the living room to sit cross-legged on the carpet by her mother’s feet, listening to her stories with the soft brush of her hand against her hair. The sitting room would become a man’s world.

Mehrunissa is primarily responsible for the family and allows her daughters freedom such as reading. whenever and whatever they desired. She does not subscribe to the belief that books and ideas were harmful for girls and that daughters were meant to be groomed for marriage. Jimmy describes the Malik home with fascination: “It was the first house I had ever been in with books in every room. Even in a room with no shelves, there were books under cups or hidden behind pots; Barbara Cartland novels tucked in the slots of the swings. Books in other houses were rare, precious thing, tucked out of reach or behind walls of glass, leather-bound and glossy. These tangible tattered things with dog-eared pages and tea stains were remarkable. I shifted my cup of tea on its coaster, knocking over a mystery novel that Mehrunissa kept beside her sewing.” Mehrunissa’s determined stand against social norms and even in the presence of her husband, in an overtly patriarchal society, is exemplified by refusing to slaughter goats for Eid: “Mehrunissa and her daughters were particularly sensitive about the slaughters. They never participated, had not done so even on the rare holidays when Captain Malik was home. On Eid, theirs was the only house with no goats or cows lined up outside—another thing among many that set them apart from everyone else he knew, another thing about them that people thought was strange.”

People called the Maliks “strange” because of it being primarily a female household living alone, happily, unheard of in an otherwise overtly patriarchal society. It was also odd that the father “permitted” the women to have their say as in the case of doing away with the practise of getting a sacrificial goat as it was an inhumane act. But love runs deep as testified by the Captain while recounting to Jimmy the kindly advice he had received about the challenges his marriage may pose: “These things are meant to work better when the differences aren’t so big, your families should come from the same place, you should speak the same languages and pray the same way – you’ll have heard all this, I know. They’d even chosen a girl for me. I never told Mehrunissa that. Baat pake se pehle—I saw her. And that was it.”

Their mother’s strong personality had a deep influence on the four daughters. They grew up with distinct identities. Maria who as a teacher’s assistant in the school mesmerised the boys: “The trick was not in her words, but the way she spoke them. She was not lightning but slow honey, womanliness pouring into the classroom, making us all sit up a little straighter.” Ayesha, the voracious reader who fantasised about her European trip with her aunt was the most level headed and practical of the sisters. For example, her unsentimental detached views on death is revelatory, “Death isn’t this big drama everybody makes it out to be… It’s – a person being there one minute, and not the next. It’s the passing of a second.” The laidback Bina’s “wishes were never for herself”. And finally Leila, who, “built her houses in gold. She wanted a rich husband, a studio of her own. I want a wardrobe the size of Marie Antoinette’s, she would say. Decadence was the only thing she took away from history lessons. She was a tiny Cleopatra, Nur Jehan, a queen in a miniature.” After Maria’s wedding “the house shrank without her, tightening around the family. There are some people who leave the room and you stop thinking about them right away. None of the Malik sisters were like that. Their absence took up room, a seat at the table.”

This Wide Night although a novel is structured like a three-act play with a shift in the voice from first person of Jimmy to the third of the authorial narrator in the second section and back to Jimmy. It is a curious literary technique to employ for it is not fully exploited by the author providing little insight such as in the sisters suicide pact. Usually the narrator brings in a perspective giving the reader a little more information than the characters are aware of but nothing of that sort happens here.

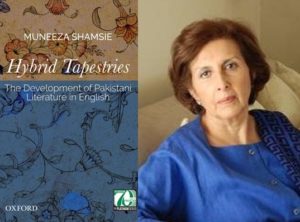

Renowned writer and critic Muneeza Shamsie says in Hybrid Tapestries: The Development of Pakistani Literature in English ( OUP, Pakistan, 2017, p 601) that in today’s globalised world the new generation of Pakistani writers have either “lived, or been educated in, Pakistan and the West, and often divided their time between the two. … As a result, the distinction between diaspora and non-diaspora began to blur too.” This underlying desire to be accepted globally as a new South Asian writer who is extremely familiar with Western canons of literature is evident in This Wide Night too for its adaptation of Little Women albeit in a desi setting. Pakistan-born now living in UK Sarvat Hasin wrote This Wide Night after enrolling in a creative writing workshop project wherein she transplanted the characters created in nineteenth century America into modern-day Karachi. So Amir, Maria’s husband, is a mujahir who lost his parents during Partition but he comes across as a flat character who, “seemed to just appear, a sum of all the stories people told about him” with little else being said about him. Whereas if a little bit of the socio-historical background was woven into the novel it would have made a significant difference to the quality of storytelling. This is illustrated further in the sanitised “literary” description of the 1971 War, a conflict zone: The way tensions rose in our house and in the city, the way the whole country seemed to teem with a dull thickening heat – the days before monsoon storms. By the time war broke out, we were almost relieved. It gave the feeling a name; something that couldn’t be quantified when it was just curfews and military men stationed outside schools or people sent back past the border. Contrast this with contemporary literature worldwide which creates a rich texture filled with details taking care to not culturally alienate the reader too much but at the same time retaining a strong regional character — acceptable traits of a global novel.

Renowned writer and critic Muneeza Shamsie says in Hybrid Tapestries: The Development of Pakistani Literature in English ( OUP, Pakistan, 2017, p 601) that in today’s globalised world the new generation of Pakistani writers have either “lived, or been educated in, Pakistan and the West, and often divided their time between the two. … As a result, the distinction between diaspora and non-diaspora began to blur too.” This underlying desire to be accepted globally as a new South Asian writer who is extremely familiar with Western canons of literature is evident in This Wide Night too for its adaptation of Little Women albeit in a desi setting. Pakistan-born now living in UK Sarvat Hasin wrote This Wide Night after enrolling in a creative writing workshop project wherein she transplanted the characters created in nineteenth century America into modern-day Karachi. So Amir, Maria’s husband, is a mujahir who lost his parents during Partition but he comes across as a flat character who, “seemed to just appear, a sum of all the stories people told about him” with little else being said about him. Whereas if a little bit of the socio-historical background was woven into the novel it would have made a significant difference to the quality of storytelling. This is illustrated further in the sanitised “literary” description of the 1971 War, a conflict zone: The way tensions rose in our house and in the city, the way the whole country seemed to teem with a dull thickening heat – the days before monsoon storms. By the time war broke out, we were almost relieved. It gave the feeling a name; something that couldn’t be quantified when it was just curfews and military men stationed outside schools or people sent back past the border. Contrast this with contemporary literature worldwide which creates a rich texture filled with details taking care to not culturally alienate the reader too much but at the same time retaining a strong regional character — acceptable traits of a global novel.

Sarvat Hasin is a writer with promise. This Wide Night is a commendable first effort.

Sarvat Hasin This Wide Night Hamish Hamilton/ Penguin Random House India, 2016, 312 pp., Rs 499 (HB)