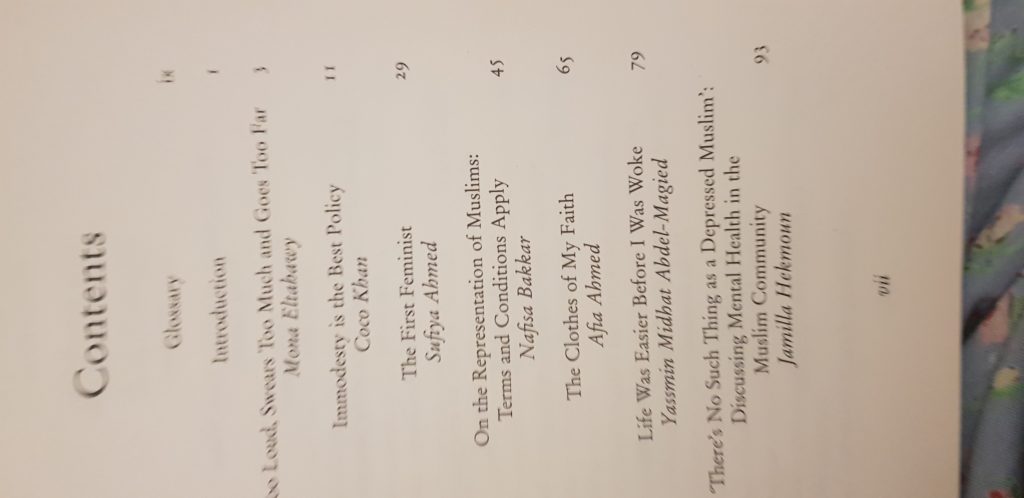

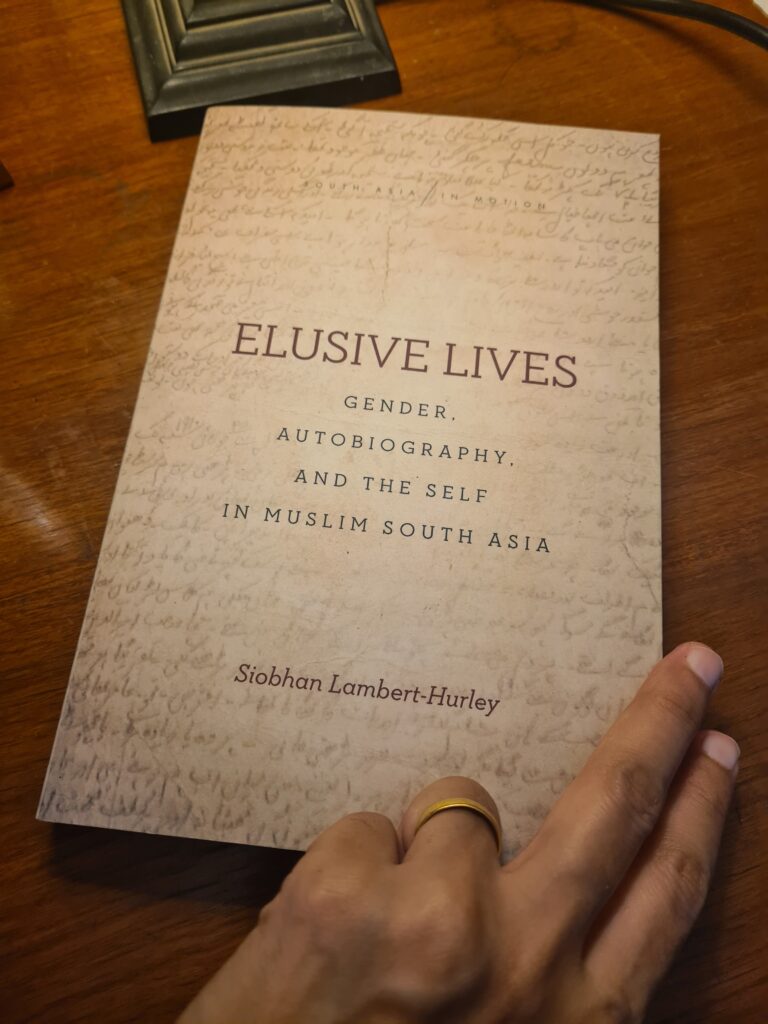

“Elusive Lives: Gender, Autobiography, and the Self in Muslim South Asia” by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley

It has been many, many months since I read historian Siobhan Lambert-Hurley’s Elusive Lives: Gender, Autobiography, and the Self in Muslim South Asia ( Stanford University Press, 2018). In Elusive Lives, she locates the voices of Muslim women who rejected taboos against women speaking out, by telling their life stories in written autobiography. It is very challenging to sum up quickly all the various arguments she presents or the close textual analysis of published and unpublished writings she accesses. She has used rare autobiographical texts in a wide array of languages, including Urdu, English, Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Punjabi and Malayalam to elaborate a theoretical model for gender, autobiography, and the self beyond the usual Euro-American frame where gender theorists have long articulated a “difference” model applicable to women’s autobiography by which their self-expression was unique in form, style, and content when compared to that of men.

This book deserves to be read from cover to cover but I am going to post some extracts here to highlight some of the very powerful ideas it proposes.

…David Arnold and Stuart Blackburn identify autobiographical writing “in the sense of a sustained narrative account of one’s own life” as emerging in South Asia in the late nineteenth century and becoming more “common” only in the early twentieth century — in other words, after the establishment of colonialism proper in 1858 and the spread of a key technology for book and journal distribution in the form of the printing press. As Ulrike Stark has traced in meticulous detail, print technology was well established in India by the late eighteenth century, but it remained largely in the hands of missionaries and British colonists in their coastal headquarters at Calcutta and Madras. It was another century before the print “boom” really took off, as technological innovations and the growth of the Indian paper industry reduced the cost of printing sufficiently to make it accessible to the Indian middle classes — who could then read, write, and circulate published autobiographies alongside other genres. The spread of autobiography mirrored the trajectory of print in the high noon of colonialism. ( p.3-4)

Autobiography functions as a vehicle for sharif redefinition above all, but also nationalism, historicism and didacticism, literary creativity and performance are higlighted alongside a more general impulse: to narrate a life momentous for Muslim women living at a particular time and place. ( p.22)

The first observation is that South Asian Muslim women writing autobiography do tend to focus on the domestice over a public persona, but since the home continued to structure their lives throughout my historical period, it might be counterintuitive to expect otherwise. Furthermore, if authors did have a career outside the hojme, they wrote about that too — just as their menfolk ofter wrote about their families or personal networks. A second observation,then, is taht the relationality is at the heart of autobiographical writing in Muslim South Asia, irrespective of gender. A third observation is that women’s writing is often fragmentary, but that quality may be as much as inheritance of a longer autobiographical tradition ( for example, roznamcha or akhbar), or a feature of the publication process, as a reflection of women’s historical lives. A fourth observation is that while modesty is a trope in the life writing of many women ( and some men too), it is not necessarily predicated on an absence of self-assertion. A fifth observation turns from “difference” to change over time. Clearly, how these authors constructed their identities, and in what language ( or form of language) they did so, was contingent on historical moments defined by some of the major events and processes of the modern era, not least among them imperialism, reformism, nationalism, ans feminism. As time progressed, so did women’s preferred autobiographical forms and their handling of certain topics — most notably intimacy, sexuality, and illness. Hence, a sixth and final observation is that the collectivities to which womenin Muslim South Asia belonged — clan, community, country — did not undermine a sense of self so much as frame their multiple and varied expressions of interiority. (p.24-25)

So, what actually is to be included in my life history archive? I startedmy fieldwork wondering if there was anything out these to be found; and throughout, I continued to face skepticisim at the idea of Muslim women writing memoirs. Without doubt, these sources can be difficult to find. While the colonial archive and its successors threw up some material, much more fruitful was the experience of getting out onto the streets and into people’s homes and lives. Through this more holistic approach to research, I colelcted literally hundreds of books, manuscripts, articls, and words relevant to this study of autobiographical writing — whether called “autobiography” or “memoir”, ap biti, biti kahani, or khud navisht, atmakatha or atma jibani, or, in more specific forms, roznamcha or safarnama. Yet, as I have sought to show, a constant problem was how to fit these real-life historical sources into the theoretcial boxes dreamt up by academics usually within the context of a Euro-American literary tradition. In the course of this chapter, then, I have traversed from autobiographical biographies and biographical autobiographies to travelogues, reformist literature, novels, devotionalism, letters, diaries, interviews, speeches, and ghosted narratives. In the end, I draw a line — if a hazy and traversable line — at the constructed life: no novels, but more autobiographical biographies and the biographical autobiographies; the autobiographical fragment; the written-made-oral ( including some film), but not the oral-made-written; the published “diary book”, but not diaries or letters; the spiritual, but not the ghosted; and the travelogue where relevant. I have thus evolved a definition for autobiographical writing that emerges from the specific experience of a historian crafting a unique archive from which to study gender, autobiography, and the self in Muslim South Asia. Having done son, I now turn from from what to who. (p.55)

Like diarists and autobiograhers in other places and times, Muslim women in India who produced personal narratives tended to be educated and often highly so– notably, at a time when few others were. Not only did they know how to read and write, but they also possessed the ability to analyze their own experiences and use them to construct a coherent narrative, often representing an individual life. Yet what this reading of Muslim women’s autobiographical writings also points to is the importance of the struggle for education: the ultimate desire to learn, even if it is denied. ( p. 75)

Also complicating autobiography’s geography were regional imbalances. Pakistan has experienced its mini memoir boom in recent years, in part fueled by the publishing interests of Oxford University Press’s managing editor in Karachi, Ameena Saiyid. She has been responsible for commissioning new memoirs by men and women alike, while also reissuing many previously published titles — some of which date back to the nineteenth century. Many Pakistani autobiographies were written by women who began their lives ( and life stories) elsewhere in South Asia before Partition transformed them into mohajirs, or migrants, most often to Karachi in Sindh, though also to Lahore. Jahanara Habibullah, for instance, dedicated twelve of her thirteen chapters in Remembrance of Days Past ( 2001) to her early years in the princely state of Rampur in north India, even though she spent the latter half of her life in independent Pakistan. At the same time, Pakistan’s provinces — especially Punjab, but also Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa — have nurtured their own female autobiographers before and after 1947. As an early example from west Punjab, we may recall how Piro used her lyric autobiographical episode, composed sometime in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, to narrate her move from a brothel in Lahore to her Sikh guru’s dera, or abode, Chathianwala. Later authors rooted their narratives in particular cities and villages– from Baghanpura, Rawalpindi, Wah, Bhera, and Meerwala in Punjab to Larkana, Hyderabad, and Kharjal in Sindh — while tracing family, tribal, or clan lineages as far back as the eleventh century.

But for all this proliferation in the northwest, autobiographical writings by Muslim women were still far more abundant in the original Pakistan’s eastern wing. In fact, Bangladesh proved to be a gold mind of resources for this project. By the end of a research trip in 2006, I had collected so many books and photocopies– from Dhaka University library, bookstores, and personal collections– that I actually had to buy a new suitcase… (p.101)

…the autobiographical act is actually far more complicated than a woman sitting alone to craft an unmediated story about her life. …South Asia’s Muslim women produced autobiographical narratives with specific audiences in mind — from an audience of one to international distribution — with varying consquences for style and content. Gendered audiences inspired gendered narratives, their topics chosen to satisfy the domesticated interests of a fictionalized sisterhood. An autobiography for real family, on the other hand, could inspire intimacy and self-censorship in equal measures. …the literary milieu was as influential in shaping a narrative’s form and content, whether that narrative was circulated as a manuscript,a journal article, or a book. In each case, the process of production introduced new actors — editors, translators, cowriters and publishers — who were complicity in the construction of the autobiography. …The framework of performance offers an effective means of theorizing this relationship by underlining how concepts of selfhood may be “staged” in autobiographical writings. By regarding the author as a performative subject — an artiste acting out her life story on the page — this approach enables an appreciation of how each rendition of a life story may be tailored to and by audience, literary milieu, or historical moment. ( p.153)

The book is available at Stanford University Press: https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=29187

25 July 2021