“Mahabharata”

DK India has published an incredibly sumptious edition of the classic epic Mahabharata. It was put together by a large in-house team working along with well-known mythologists and Mahabharata experts. It has resulted in this extraordinarily beautiful edition, impressive design, detailed page layouts where the text and illustrations complement each other well and incredible layers of information. In a sense the publishers have achieved practically the impossible of transfering the layered and embellished narrative style of oral storytelling into the fixed printed form.

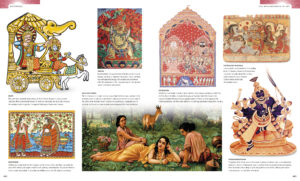

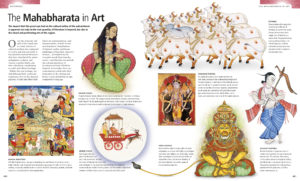

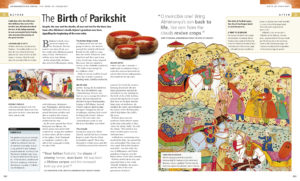

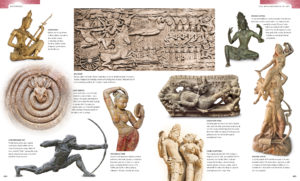

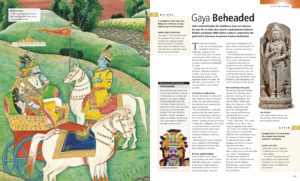

The story is told through the 18 parvas as is in the familiar arrangement of the oral epic. As far as possible the structure of the oral narrative tradition has been adhered to in this print version. Every page a small portion of the story is narrated in simple English making it accessible to other cultures too. To accompany the text every page has been specially designed with different elements relevant to that particular context. These could vary from boxes on cultural details, mythology and folklore associated with the particular story, prayers and rituals passed through the ages, references to the versions of the epic/characters in art and literature, photographs of modern-day dance and theatre interpretations of the stories and a liberal sprinkling of historical artefacts and monuments that may help  illustrate the text.

illustrate the text.

I interviewed Alka Ranjan, Managing Editor, Local Publishing, DK India who led the team which put together this book. Here follow edited excerpts of an interview published by Scroll.in on 20 August 2017:

1. Which version of the epic did you refer to?

We were keen to tell the entire story of the Mahabharata, including the Harivamsa, and, wherever possible, dip into the regional versions as well. To be true to the classical version, we referred to Bibek Debroy’s ten volumes of the Mahabharata, from where came some of the details of the stories and also the quotes.  Ultimately for DK India it was the visual rendering of the epic which was more important, something that was not attempted before, and something that makes our book unique, setting it apart from the other books available in the market.

Ultimately for DK India it was the visual rendering of the epic which was more important, something that was not attempted before, and something that makes our book unique, setting it apart from the other books available in the market.

2. How long did this project take to execute from start to finish?

It took us almost 8 months to put together this book. To this we could also add 3 months of production. The entire team, including the technical members, reached 15, in some stages of the book.

3. Does DK have other religious texts illustrated in a similar fashion? Was there anything unique as a publishing experiment in this book?

a publishing experiment in this book?

DK has brought out the Illustrated Bible in the past. This book is in the same series style. Unlike our other reference books which work mostly like non-fiction with their dry, neutral tone, our version of the Mahabharata is yet another retelling of the epic. It was a challenge for the editorial team to adapt their skills to storytelling, to ensure the text flowed like a tale, weave in dialogues wherever needed, and inject drama to create impact.

4. It seems to be meant for the general market but the stories are easily told that a child too can read them. If that is the case then how did you manage such a gentle and easy style?

Our aim was to keep the stories accessible for a large readership, and in a lot of ways that is DK style. While we segregate our books in adult and children categories, depending on subject matter, comprehension level, interests, so on and so forth, the text for the adult ones is almost always aimed at ages 14 and above.

5. If you could have a section on “Mahabharata in art” why not have a section on the history of texts through the publication of this epic through the ages?

through the publication of this epic through the ages?

We could have done so many things with our book, but because it was going to be a visual retelling we decided to focus on art, showcasing the pervasive reach of the epic in our daily lives, and which made more sense, although a lot of our “boxes” talk about the different versions of  the epic, including drawing parallels with Greek mythos.

the epic, including drawing parallels with Greek mythos.

6. This epic has been translated in other languages. Why not have images of those texts at well?

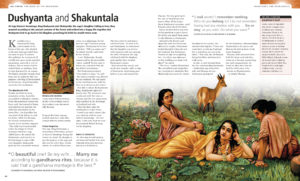

It was not always possible to get all images that we wanted, but we have used a couple of book covers to make the point about translations or different takes on the epic – mostly for latter. I can think of a book on Yudhishthira and Draupadi by Pavan K Varma which we used to discuss their relationship. We also used Mrityunjaya’s cover (Shivaji Sawant’s much celebrated book on Karna) on Karna’s profile. The choice of other retellings of Mahabharata invariably depended on the context of the stories we wanted to tell and the point we wanted to make and not the other way around. Some of the other books that find mention in ours are:

Kalidasa’s Abhijnana Shakuntalam

Tagore’s Chitrangada (with cover image)

Pavan K Varama’s Yudhisthira and Draupadi (with cover image)

Krushnaji Prabhakar Khadilkar’s play Kichaka-Vadha

Dinkar’s Kurukshetra and Rashmirathi

Shivaji Sawant’s Mrityunjaya (with cover image)

Bhasa’s play performance by Japanese students – Urubhangam

7. It would have been fascinating if a chapter on myth-making  in this epic had been included as a standalone chapter rather than inserting boxes in various chapters. Why not address myth-making?

in this epic had been included as a standalone chapter rather than inserting boxes in various chapters. Why not address myth-making?

I take your point, and it would have been certainly interesting to have such a chapter now that you point it out. However, when we conceptualized the book, we were sure that we wanted the focus of the book to be on retelling the epic and layering them by adding side stories in boxes. We also wanted to have a few chapters/spreads on Hindu gods and goddesses, and philosophies, mainly to facilitate the understanding of the non-Indian readers, people not familiar with our cultural ethos.

8. How did you standardise the spelling of the names? What’s the back story to it?

We wanted us to use the more common spellings of the popular characters (Draupadi instead of Droupadi), although we did finally add the vowel sound at the end of some names, for instance “Arjuna” instead of “Arjun”, “Bhima” instead of “Bhim”, which takes the names closer to their Sanskrit pronunciation, but stuck to “Sanjay” not “Sanjaya” because it was a more common spelling.

9. Does the text of the books mentioned conform to the original text or have some creative license liberties been taken to retell it for the modern reader?

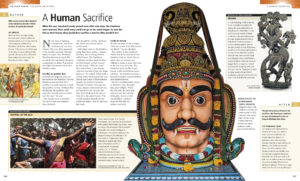

While most of our stories came from the original, classical text, we also dipped into the regional versions to borrow a few. For instance, Iravan’s story (A Human Sacrifice) came from the Tamil Mahabharata. Few other stories borrowed from regional versions are : Pururava’s Obsession

Draupadi’s Secret, Gaya Beheaded, Divine Vessel, News of Home, The Talking Head

10. Would you be creating special pocket book editions of relevant chapters? For instance I see potential in the section on women. If you had to resize it to a pocket edition with an introduction +original shlokas, the sales would be phenomenal.

Thank you so much for the suggestions. The book does lend itself to several spinoffs, and we have thought of a few. However, we wanted the current book to run its course before bringing out another one.

20 August 2017