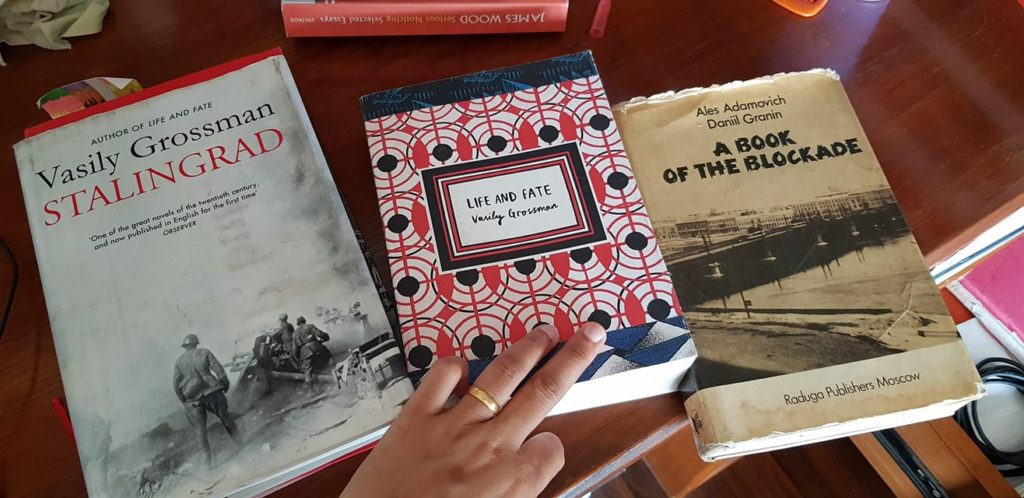

Vasily Grossman’s “Stalingrad”, translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

Vasily Grossman”s Stalingrad is a prequel to Life And Fate. Life and Fate (Russian edition, Soviet Union, 1988) was translated from Russian into English in 1985 by Robert Chandler and Stalingrad ( 1952, Russian edition) in 2019 by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. Life and Fate had been completed by Grossman before he succumbed to cancer in 1964 but the English translation was published before permission was granted for the Russian edition. It became possible after glasnost.

Vasily Grossman was a correspondent in World War Two. His novels borrow heavily from all that he witnessed. Recently, Robert Chandler wrote a magnificent essay, “Writer who caught the reality of war” ( The Critic, July/August 2020 ). Grossman was a correspondent for Red Star, a daily military newspaper as important as Pravda and Izvestia, the official newspapers or the Communist Party and the Supreme Soviet. It was a paper read by both military and civilians. Chandler writes “According to David Ortenberg, it’s chief editor, Grossman’s 12 long articles about the Battle of Stalingrad not only won him personal acclaim but also helped make ‘Red Star’ itself more popular. Red Army soldiers saw Grossman as one of them– someone who chose to share their lives rather than merely to praise Stalin’s military strategy from the safety of an army headquarters far from the front line.”

Stalingrad is a massive book to read at nearly 900 pages. I read Constance Garnett’s translation of War and Peace in three days flat but Stalingrad was far more difficult to read. Perhaps because it was written so close in time to the events it describes. Within a decade of the Stalingrad blockade by the Nazis, Grossman’s novel had been published. Whereas “War and Peace” was written fifty years after the events fictionalised by Tolstoy. It makes a difference to the flavour of literature. Reading “Stalingrad” during the lockdown is a terrifying experience. More so because today nations around the world are dominated by right wing politicians who see no wrong in implementing xenophobic policies. The parallels with Grossman’s accounts are unmistakable. Having said that I am very glad I read Grossman”s novel. It is a detailed account of the blockade using the polyphonic literary technique. Sometimes it can get bewildering to keep track of so many characters. Also because there are chunks in the text over which Grossman does not have a very good grasp. His details of the battlefield or the stories about the Shaposhnikovs are his strongest moments in the novel. Perhaps because the war scenes are first hand experiences, much of which is brilliantly accounted for by Chandler in his recent article. And the weaker portions were written during Stalinism and Grossman probably had to be careful about what he wrote for fear of being censored.

After reading Stalingrad, I reread portions of Ales Adamovich and Daniil Granin’s A Book of the Blockade ( English translation by Hilda Perham, Raduga Publishers, Moscow, 1983; Russian edition, 1982). This book is about the nine hundred day siege too. The auhors recreate the event by referring to diaries, letters, poems written during the blockade, and survivors’ testimonies. They also interviewed “the strong and the weak, and those who had been saved and those who had saved others”. At times it felt as if there was little difference reading Grossman’s novel or these eye witness accounts that had been gathered by Adamovich and Granin.

These are very powerful books. I am glad the translations exist. Perhaps this kind of war literature is not everyone’s cup of tea, especially during the lockdown but it is highly recommended. Sometimes it is easier to understand our present by hearkening back to the past. These books certainly help!

Moscow, 1942. Summer.

There were several reasons why people felt calmer … it is impossible to remain very long in a state of extreme nervous tension; nature simply doesn’t allow this.

Stalingrad

7 July 2020

expect a no. The portrait artist too falls under Menshiki’s spell even though he knows he is going to be paid very well for the commissioned portrait. The conversation is lack lustre. The women in the novel whether the ex-wife, the various mistresses, the young 13 year old daughter of Menshiki born of an affair he had a long time ago are reduced to sex objects. It is absolutely bizarre that the pre-pubescent girl is so obsessed by her breasts and her first frank conversation with the artist is about her chest size. It is ugly.

expect a no. The portrait artist too falls under Menshiki’s spell even though he knows he is going to be paid very well for the commissioned portrait. The conversation is lack lustre. The women in the novel whether the ex-wife, the various mistresses, the young 13 year old daughter of Menshiki born of an affair he had a long time ago are reduced to sex objects. It is absolutely bizarre that the pre-pubescent girl is so obsessed by her breasts and her first frank conversation with the artist is about her chest size. It is ugly.