Interview with photographer, Parul Sharma

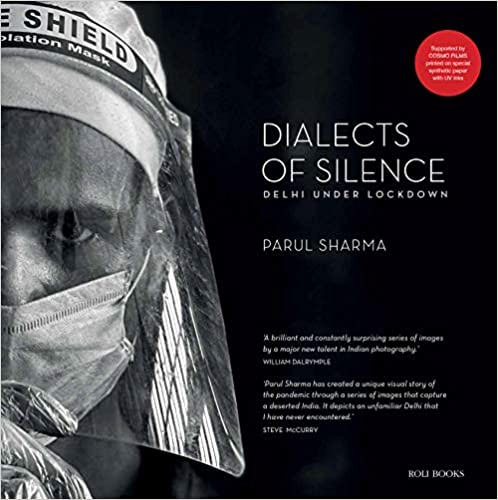

In June 2020, I came across on social media a series of black and white photographs that were extremely shattering. They were images from the Nigambodh crematorium in Delhi showing the cremation of Covid19 patients. These images were terrifying as the images put the spotlight on the extreme loneliness of the dead. Usually funerals in India are an excuse for a massive gathering of mourners. These black and white photographs were in stark contrast to what we normally experience, across faiths, during funerals. The photographer was Parul Sharma who it turned out was working on a book of photographs called Dialects of Silence: Delhi Under Lockdown ( Roli Books).

The book is a haunting documentation of what Delhi looked like when the lockdown began in March 2020. Understandably few were out on the streets. Only essential services were permitted. News would filter through the media or there were social media posts that would give some sense of what was happening in the world. But to see a series of images in quick succession, full-page or double-page spreads, is a disturbing experience. When I posted the Open Magazine link on Facebook, many folks asked me why did I think it was necessary to post links to such distressing images. I did not have a satisfactory reply but I knew I needed to speak to Parul urgently and soon. So I did. Here is a lightly edited version of the intervew we conducted via email.

In a span of three years of her photography, Delhi based, Parul Sharma has won critical acclaim for producing a large and diverse body of work. Her metier blends architectural design, and human form in urban landscapes. Her works first debuted in July 2017 in a solo exhibition “Parulscape” at Delhi’s iconic Bikaner House. Forbes magazine marked its 10th anniversary in India by inviting her to shoot ten photographs that captured change and freedom in a decade. In December 2019, Florence’s public art centre, the Museo Marino Marini, exhibited her images of Naga Sadhus and Transgenders at Kumbh Mela. Titled “Mistico India” the two-week exhibition exposed Italian art lovers, to the fierce vibrancy and colours of devout Hindus.

Dialects of Silence, Delhi under lockdown was published and released by Roli Books on September 1 2020 and has received acclaim in India Today, The Hindu, Hindustan Times, Indian Express, Open, and BBC among others. Her next book due for release in 2021, commissioned by Roli books is an essay on Mumbai’s historic Art Deco Colaba district.

- What sparked the idea to photo-document Delhi NCR during the lockdown? NCR during the lockdown? What did you intend on documenting when you began this project? Did you achieve it or did the goalpost shift during the project?

It began as a visual archive of a city and ended up as epidemic photography. It was an attempt to seize, to put a context of this extraordinary situation that was unravelling before us against the tragic backdrop of the pandemic. Some stories just get told regardless of travesty, sacrilege or homage. The images remain as bearing witnesses. - How did you get the permission to take the pictures that you have taken?

After obtaining necessary approvals from the authorities. - It is interesting that you quote the great war photographer Robert Capa in the introduction to a book on Covid19. Did you feel that while documenting the effect of the pandemic it was like being in a war zone[i]?

Absolutely! A pandemic is a war of invasion, a tragedy, a horror. War evacuates, shatters, and breaks apart the notion of a built world. The virus did the same. Photography during such times is like being in a line of fire, you could get infected anytime. - Being a photographer is an interesting experience. It is an immersion in the space, recording moments, while the camera lens permits a distancing from the immediate events. Yet, your images are extremely respectful of the subjects in your compositions. Your photographs never come across as a violation of the individual’s privacy. How do you achieve this?

You have to put yourself in the other persons situation and share their pain. You cannot be a self-serving voyeur. You have to be very much a part of their story and their grief and their survival and their triumph. Your picture is merely a text of their context.

It is easy to pity the people in images if the viewer has never experienced or come close to experiencing the situation that is being shown. Yet, this emotional response is still valuable because it draws attention to the situation in which people can further investigate their curiosity about the image. Such images are an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations of suffering. Who caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible?” Epidemic photography can serve as memento mori, important tokens of a nation’s collective memory. - The angles of your shots are fascinating. Sometimes you crouch, sometimes you use a telephoto lens, sometimes you are pretty close up. Do you script your stories before stepping out for the day with your cameras or do you take them spontaneously?

Mostly it jumps out of you. Photography is to seize that particular shot which if lost will never reappear. You are a surfer who can ride that visual wave or go under. I have never so far planned a shot. It’s there. You see it. You shoot it. - The portraits of the doctors scarred by the masks is alarming. The exhaustion in their eyes at the start of the lockdown is haunting. Once the book was published, did you return to photograph your subjects once more?

I started documenting in April and the book came out in September. I haven’t paused yet as I’m still documenting. I definitely plan to revisit most places and people. - The images at the crematorium are unforgettable. The loneliness and horror of the bodies trussed up and being managed by individuals well-protected in their PPE gear is devastating. Will you ever do a travelling exhibition of these images?

Certainly. - Why is religion a fundamental focus of your images? Was it a conscious decision to document the various kinds of rituals embedded in our culture that help us to come to terms with death and grief?

Just as religion and faith is fundamental to our being, photography is also fundamental to either the beauty or ugliness of truth.

The surreal interchangeability of workers at the crematorium or the Muslim burial ground or the cemetery were a stark testimony that in COVID deaths of any religion the bodies, were wrapped in the same grim ducted plastic to the point of indistinguishability. - How did you disinfect your cameras?

Disinfecting wipes / Soap and Water /70% Isopropyl Alcohol. After disinfecting I would leave the equipment and set it aside for 48 hours. - What would you call this collection of images — art or a witnessing in the form of photo-documentation?

To quote Sontag, “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability.” You may call it art or documentation; the lines are interjecting. - Where and when did you learn photography?

I have had no formal training in photography and not did I ever think I will become one. I shoot instinctively. Though someday I do want to do a formal course.

12. Who are the photographers who have influenced you?

I have deep admiration for photographers who photograph in conflict zones. Richard Drew, Hector Retamal, Nick Ut, and from the past Robert Capa, to name a few.

[i] The poet Michael Rosen who is recovering from a severe bout of Covid19 likens it to being in a war. (“Michael Rosen on his Covid-19 coma: ‘It felt like a pre-death, a nothingness’ The Guardian, 30 Sept 2020)

14 Oct 2020