The Decameron 2020

Portrait of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1975) Stefania Lotti

In May 2020, I was sent a YouTube link by academic and novelist Tabish Khair. It was a short clip of film actress Shabana Azmi reading a story. I began to listen. I realised it was a brand new story written by Tabish Khair. Soon we were exchanging furious messages over WhatsApp. I had a 1001 questions to ask him about the project — The Decameron 2020. Ever since I discovered the project, I have been listening to the stories on a loop.

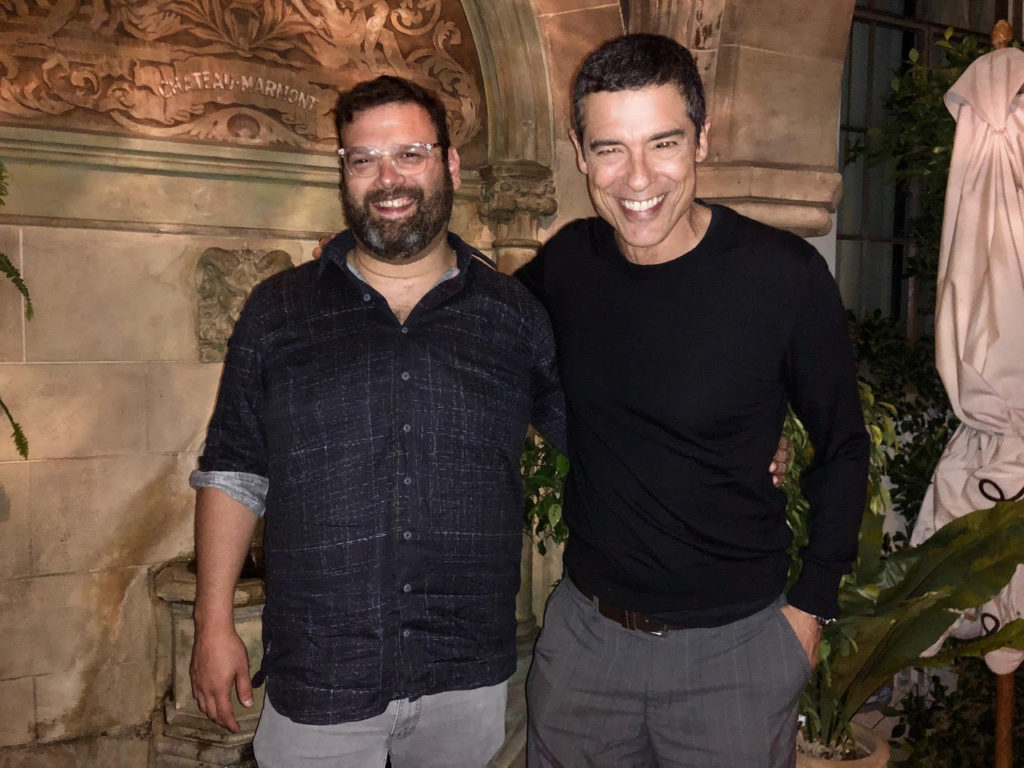

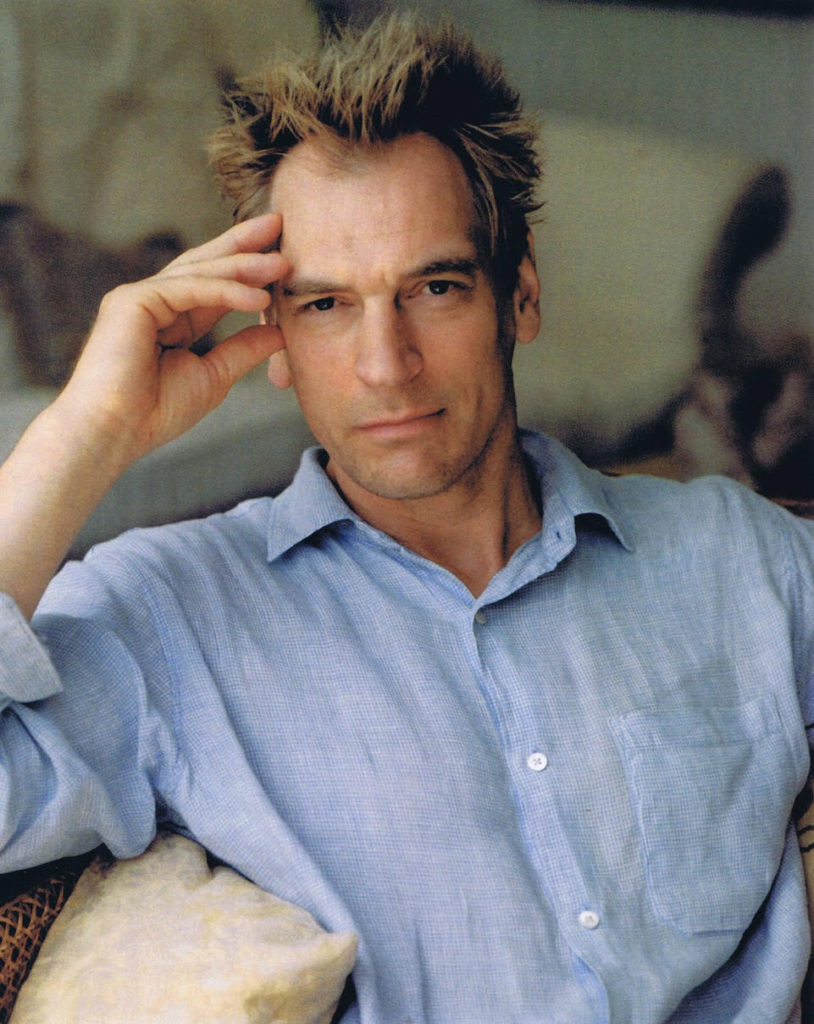

The Decameron 2020 is a collaborative project of like-minded creative folks. The unifying factor is their ability to tell stories magnificently. The differentiating factor is the medium they opt to tell their stories. This extraordinary project is the brainchild of the Italian novelist, translator and poet Erri de Luca. According to him, “We imagined short novels because, in times of distress, we need to concentrate our words in the same narrow place we are restricted in. We imagined isolated actresses and actors around the world who give their voices as oxygen for the breathless.” His colleagues are producer Paola Bisson, filmmaker Michael Mayer, the Spanish publisher Elena Ramirez and Jim Hicks, Executive Editor, The Massachusetts Review. The Decameron 2020 project invites storytellers around the world to submit original stories for the project. These stories are then read out aloud by professional storytellers, mostly film actors such as Julian Sands, Fanny Ardant, Pom Klementieff and Alessandro Gassman. They read against a backdrop created by Richard Petit, co-founder and Creative Director, The Archers, whose mesmerising artwork unites these distinctive stories. Commenting upon the creation of these unique backdrops for the Decameron performances, Richard Petit says, “The experiences – both reading these extraordinary texts and responding to them visually – have marked this period of social isolation in an unforgettable way. Beginning by depopulating the masterworks of Florentine artists – in many cases, contemporaneous to Giovanni Boccaccio’s original setting – and collaging them with fragments from works by Italian Futurist painters, my goal has been to create beautiful but somewhat disquieting stage settings that visually connect these stories of quarantine, separated by nearly seven hundred years.”

It is an extraordinary layering to the original story. Much more than just a dramatic performance. There is something quite special about the telling. It is almost as if one has to as a listener be present “within” the storytelling, shut out all the sounds of life around one, and be wholly immersed in the storytelling. It is like recreating the experience of being “locked in” the story to experience it. I have no other way of describing it.

Erri, Julian Sands, Paola, and Alvaro Rodriguez

Tabish Khair

Pom Klementieff

Stèfi Celma

Alvaro Rodriguez and Alessandro Gassmann

Julian Sands

Pictures provided by Paola Bisson and Michael Mayer.

These are surreal times. I like the parallels drawn with a war zone by Jim in his essay since it enables an experimentation with the story form too. There are no expectations of the writer / actor / listener about the act of storytelling. The story gets completed in the classic sense by the listener’s participation. Yet it is storytelling at a global level with the stories/performances such as Luigi Lo Cascio’s having a very rich local texture. What comes through beautifully is the shock everyone feels at the sudden end of life as we knew it. There is no precedence for such a global catastrophe. So behavioural changes cannot be mimicked. Nor is there any memory of such an experience being handed down generations. There is no witnessing of it either by those alive today. As a disaster management expert told me recently, “Difficult to find a narrative for what we are going through”.

It is also precisely why I am very intrigued by The Decameron 2020 project as it tries to make sense of our new world. The creative experimentation of making writers and film actors to collaborate while in isolation and across time zones is extraordinary. It lends itself to many interpretations in the performance of putting the readings together. If everyone had been together in a room ideating, there would have been multiple layers and I am guessing a completely different output. Instead working remotely, across time zones, the onus is upon every individual involved at different stages of production to interpret the story for themselves. Ultimately every stage — writing, reading out aloud, recording, editing, adding a unique backdrop, publishing on YouTube, listening — add layers to the performance. It is palpable but not disruptive to the experience.

The Decameron 2020 team were very kind in replying to some of my questions. So here is an edited version of the interview:

Q1. What sparked this idea for The Decameron 2020? ( Btw, did you know that #DecameronCorona has been started by Daniel Mendelsohn on Twitter?)

Erri: The Decameron and Boccaccio are pillars of our literature, so the idea sprang shape to Paola Bisson and me. We imagined short novels because, in times of distress, we need to concentrate our words in the same narrow place we are restricted in. We imagined isolated actresses and actors around the world who give their voices as oxygen for the breathless.

Paola: I can add that I had a personal need to reverse my isolation and discomfort in this “pandemic” time into a new alliance. I felt like a truck driver who sends radio messages looking for other drivers on the same highway, to share the journey.

Michael: When Paola talked to me about it for the first time I had to wrap my head around the logistics of such a project. We all knew it was going to be a challenge, but the creativity and ingenuity of everybody involved was really inspiring to me. Everybody who joined us has had such a positive and easy attitude that we were able to tackle all the practical obstacles.

Q2. How were the authors for this project selected? Who are the writers and actors invited to participate in this series?

Erri: As the epidemic covers the planet, we wished to invite writers of all the continents, to form an ideal chain with the exceptional readers of their tales.

Paola: The authors of this project were suggested by us (Erri, Michael and me), and by the precious help of professor Jim Hicks and the Spanish publisher Elena Rico Ramirez. The French publisher Gallimard (they publish Erri’s books) connected us with Violaine Huisman…but the “brigata” is still growing with new suggestions.

Michael: Erri and Paola know so many wonderful and talented writers and with the help of Elena Rico Ramirez and Professor Jim Hicks were able to reach even more.

Q3. What is the brief given to the author when commissioning the story?

Erri: We asked authors to write pages from the unpredicted siege, no limit to the argument, just to be read in around five minutes. Then the director Michael Mayer gave hints and guidelines for the video.

Paola: The brief was written by heart, at least for me…I learned English in the US, watching movies. For once in a while, I have been shameless writing to everybody.

Michael: No brief, except trying to keep it around 700-1000 words. Some writers submitted a short story, one wrote a letter, another a poem, while others gave us their personal journal entries. So far it has been an absolute privilege reading all their wonderful contributions.

Q4. Are the actors decided beforehand or are they selected after the story is submitted? Is it imperative that the writer and the actor have to belong to the same nation as in the case of Tabish Khair and Shabana Azmi?

Erri: There are no rules for the interpreters; with my story, the British actor Julian Sands accepted to give his voice and talent for the character of the tale.

Paola: Everything has been a pure collaboration and mutual suggestion. Still, The Decameron 2020 is growing this way.

Michael: Every case is different. Dareen Tatour, a Palestinian poet, asked that her poem be read in Arabic, by a woman. Fang Fang asked that her diary, originally in Chinese, be read in Spanish, or English. Other writers had no specific requests. Naturally, we treat every request with utmost respect, even if it means taking longer to find the right talent for each story.

Q5. When will the project conclude? Or will it continue as long as the lockdown continues?

Erri: Paola Porrini Bisson and Michael Mayer decide the terms.

Paola: I hope it will last forever, like an anti-pandemic vaccine.

Michael: We originally intended to do 10 stories, but soon realized we had so many beautiful tales, we had to extend the project. To me, The Decameron 2020 is no longer about the pandemic, but about the connections created among artists and about having a chance to collaborate with people you wouldn’t necessarily have had the opportunity, or even the reason to collaborate with.

Q6. How was the production team selected? How did the collaboration happen? What are the pros and cons of working remotely to put together such a magnificent creative project?

Erri: Paola was the producer of last Michael Mayer’s movie, Happy Times, so the essential team was there. We got the strong help of Elena Rico Ramirez, Spanish publisher. From my point of view, there is no pro, working in distant time zones, which reduces the mutual exchange of a few hours. To match it, we are engaged at every hour.

Paola: I work since ever with Erri. I am also the President of his Foundation. With Michael, I started collaborating a few years ago in a film project. With time we became friends too. Last year we made a movie together.

Michael: Paola, Erri and I recently finished working on a feature film together, so luckily we had a pool of talented people we already had a relationship with.

A big con is the challenge of communication.

The biggest pro for me is the necessity to learn to let go. This project forces me to let go a lot of control, as actors film themselves on the other side of the world. It’s a humbling experience as a director.

Q7. How do you accommodate diverse languages?

Erri: In my case, my Italian has been translated into English by professor Jim Hicks, a good friend who has supported in every way the project since the beginning.

Michael: Between all the members of our little team, we cover 6 or 7 languages.

And we’re not shy when it’s time to ask for help!

Q8. How is The Decameron 2020 being promoted across platforms? How do you find your audience?

Erri: I am poor in this matter; I just agreed about everyone’s free contributions, and the network.

Michael: Social media, personal contacts, press announcements and word of mouth.

Q9. What are the pros and cons of creating stories solely for the Internet?

Erri: No publishers, no paper, no cellulose from trees: I think that a writer has to be generous and share for free a part of his tales.

Michael: The ease of use and the ability to reach a global audience. For a project of this sort, I can’t think of a con.

Q10. In the past year there have been major shifts in the way films have been released in theatres and on subscription TV. Now the pandemic has forced many film producers (at least in India) to consider releasing their films first on television and later when cinema halls reopen via traditional distribution channels. Plus, the Global Film Festival has been made available for free on YouTube. Do you think these rapid shifts in storytellers finding their audiences will impact the future of storytelling? If so, how?

Michael: I am not much for making predictions but I believe there is room for all types of media and formats and I believe new technologies add to our media landscape rather than cannibalize it.

Q11. What next? When the world opens up, will you develop similar projects?

Michael: Having worked now with all this diverse talent from all over the world I can’t imagine restricting my work to just one nationality or language. So yes, I definitely hope so.

Jim Hicks sums up the project beautifully in this note he emailed:

I suspect that, like most good ideas (and, of course, Margaret Mead is invariably quoted in such contexts), everything begins with a “small group of thoughtful, committed citizens.” You begin by working together, and inevitably each person brings in others, and the network expands progressively, sometimes exponentially, getting richer and stronger as it grows. Though I believe that Erri’s original idea was for a “Decamerino” of ten writers and ten actors each telling one story, and I also believe that there are already at least that number in the pipeline, as Paola writes, when something is clearly working, there’s certainly no reason to quit, so this “Decamerino” could well add additional rooms, even becoming a house with many mansions, so to speak. And it is exciting to see Boccaccio inspiring so many projects today… another is unfolding at the online magazine Words Without Borders.

Personally, what excites me most about this project is Erri’s idea that from a variety of corners, all across the globes, collaborators can come together, sharing a great variety of stories and styles that, like a grand quilt, create a record and response to this global lockdown, but also a refusal of imposed isolation. Breaking the siege. Years back, I heard a talk given by another friend and frequent collaborator, the activist, poet, essayist, and translator Ammiel Alcalay; he described how a rather simple project of translation and editing, in the right place and time, could have a truly profound effect, and help to break a different sort of siege. Not that long ago, Ammiel worked to put together an anthology of Israeli Arab writers, some of whom had never before appeared in print, and some of whom lived literally blocks away from each other, but had never even met until their work appeared in the pages of a single book. For me, the chance to find great work, and great souls, from all around the planet, makes Decameron 2020 an incredibly exciting project, one that I’m both honored and enthused to put my energies, and what little talent I have, into…

For now, have a listen to the stories uploaded (at the time of writing) on YouTube:

Luigi Lo Cascio – “A message for my friends in isolation.”

Julian Sands reading Erri De Luca – “A Novella from a Former Time”

Shabana Azmi reading Tabish Khair “River of no return”

Pom Klementieff reading Violaine Huisman – Field Munitions

Mouna Hawa reading Dareen Tatour – “I… Who am I?”

Alessandro Gassmann reading Álvaro Rodríguez – “The Eternal Return of Chet”

Enjoy!

29 June 2020