Nowadays it is perhaps taken rather for granted that computers can replace other machines, whether for record-keeping, photography, graphic design, printing, mail, telephony, or music, by virtue of appropriate software being written and executed. No one seems surprised that industrialised China can use the same computer as does America. Yet that such universality is possible is far from obvious, and it was obvious to no one in the 1930s. That the technology is digital is not enough: to be all-purpose computers must allow for the storage and decoding of a program. That needs a certain irreducible degree of logical complexity, which can only be made to be of practical value if implemented in very fast and reliable electronics. That logic, first worked out by Alan Turing in 1936 implemented electronically in the 1940s, and nowadays embodied in microchips, is the mathematical idea of the universal machine.

Nowadays it is perhaps taken rather for granted that computers can replace other machines, whether for record-keeping, photography, graphic design, printing, mail, telephony, or music, by virtue of appropriate software being written and executed. No one seems surprised that industrialised China can use the same computer as does America. Yet that such universality is possible is far from obvious, and it was obvious to no one in the 1930s. That the technology is digital is not enough: to be all-purpose computers must allow for the storage and decoding of a program. That needs a certain irreducible degree of logical complexity, which can only be made to be of practical value if implemented in very fast and reliable electronics. That logic, first worked out by Alan Turing in 1936 implemented electronically in the 1940s, and nowadays embodied in microchips, is the mathematical idea of the universal machine.

In the 1930s only a very small club of mathematical logicians could appreciate Turing’s ideas. But amongst these, only Turing himself had the practical urge as well, capable of turning his hand from the 1936 purity of definition to the software engineering of 1946: ‘every known process has got to be translated into instruction table form…’ ( p.409). Donald Davies, one of Turing called programs) for ‘packet switching’ and these grew into the Internet protocols. Giants of the computer industry did not see the Internet coming, but they were saved by Turing’s universality: the computers of the 1980s did not need to be reinvented to handle these new tasks. They needed new software and peripheral devices, they needed greater speed and storage, but the fundamental principle remained. That principle might be described as the law of information technology: all mechanical processes, however ridiculous, evil, petty, wasteful or pointless, can be put on a computer. As such, it goes back to Alan Turing in 1936.

( Preface, p.xvi-xvii)

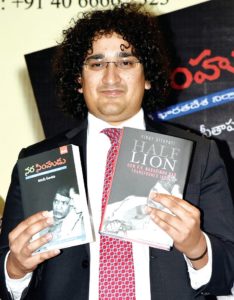

Alan Turing: The Enigma a biography of the eminent mathematician by another mathematician, Andrew Hodges was first published in 1983. As with good biographies, it balances the personal, plotting the professional landmarks, with a balanced socio-historical perspective, giving excellent insight in the period Alan Turing lived. Whether it is the history of physics branching off into this particular field of mathematics, Alan Turing’s significant contribution to it, becoming a part of the team at Bletchley Park as a code breaker, and of course his personal life — the bullying he experienced at school, his homosexuality, the friends he made and his relationship with his family, especially his mother.

This biography is so much in the style of biographies written in the 1960s to 1980s — packed with detail. This is the major difference from the twenty-first biographies which are more in the style of bio-fiction than biographies. Yet it is fascinating to see how Alan Turing in a sense has been “resurrected” by twenty-first century concerns such as importance of the Internet, computers available 24×7 and of course his homosexuality, his struggles and his suicide. Then there is Turing’s genius. His gift for fiddling with maths and science. Decoding the Nazi messages. A great deal of credit goes to Andrew Hodges for keeping Turing’s memory alive and updating the information regularly especially at a time when bio-fic is fashionable. This is an old-fashioned biography where details about the life of the person with dates, snippets of correspondence, plenty of research ( constantly updating it as official files were declassified), minutely recording events and visits to places that may have relevance to the book. The book is fascinating for its detailed history of the evolution of mathematics as an independent discipline, the differences between science and maths and explaining how Turing broke away from the shackles of eighteenth and nineteenth century thought where maths was considered to be an integral part of the sciences. Turing’s biggest achievement was the original applications in maths relying upon the principles he learned in physics, especially experiments in quantum mechanics. The book has footnotes and a preface that has been updated for this special film tie-in edition, to coincide with the release of the Oscar-winning film, The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch. This biography has been in print for more than 30 years. It was last revised in 1992, but this special paperback edition has been reprinted with a new preface by Andrew Hodges, updated in 2014. In fact Newsweek carried an excerpt from it: ( Andrew Hodges, “The Private Anguish of Alan Turing”, 13 Dec 2014 http://www.newsweek.com/private-anguish-alan-turing-291653 ). Graham Moore who adapted the book for the film won an Oscar for his efforts, but as this post from Melville House makes it clear, this script was always meant to win awards. ( http://www.mhpbooks.com/the-imitation-game-and-the-complicated-byproducts-of-adaptation/ ) L. V. Anderson of Slate points out that that the biopic is riddled with inaccuracies. “I read the masterful biography that the screenplay is based on, Andrew Hodges’ Alan Turing: The Enigma, to find out. I discovered that The Imitation Game takes major liberties with its source material, injecting conflict where none existed, inventing entirely fictional characters, rearranging the chronology of events, and misrepresenting the very nature of Turing’s work at Bletchley Park. At the same time, the film might paint Turing as being more unlovable than he actually was. ( L. V. Anderson, “How accurate is The Imitation Game?”. 3 dec 2014. http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2014/12/03/the_imitation_game_fact_vs_fiction_how_true_the_new_movie_is_to_alan_turing.html )

Richard Holmes in an article published in the NYRB, “A Quest for the Real Coleridge”, ( 18 Dec 2014, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2014/dec/18/quest-real-coleridge/?pagination=false ) explained the two principles that govern the methodology for the biographies he writes. According to him these are –the footsteps principle ( “the serious biographer must physically pursue his subject through the past. Mere archives were not enough. He must go to all the places where the subject had ever lived or worked, or traveled or dreamed. Not just the birthplace, or the blue-plaque place, but the temporary places, the passing places, the lost places, the dream places.”) and the two-sided notebook concept ( “It seemed to me that a serious research notebook must always have a form of “double accounting.” There should be a distinct, conscious divide between the objective and the subjective sides of the project. This meant keeping a double-entry record of all research as it progressed (or as frequently, digressed). Put schematically, there must be a right-hand side and a left-hand side to every notebook page spread.”). Richard Holmes adds, “He [the biographer] must examine them as intelligently as possible, looking for clues, for the visible and the invisible, for the history, the geography, and the atmosphere. He must feel how they once were; must imagine what impact they might once have had. He must be alert to “unknown modes of being.” He must step back, step down, step inside.” This is exactly what Andrew Hodges achieves in this stupendous biography of Alan Turing. Sure there are moments when the technical descriptions about mathematics become difficult to comprehend, yet it is a readable account. The author bio in the book says “Andrew Hodges is Tutor in Mathematics at Wadham College, Oxford University. His classic text of 1983 since translated into several languages, created a new kind of biography, with mathematics, science, computing, war history, philosophy and gay liberation woven into a single personal narrative. Since 1983 his main work has been in the mathematics of fundamental physics, as a colleague of Roger Penrose. But he has continued to involve himself with Alan Turing’s story, through dramatisation, television documentaries and scholarly articles. Since 1995 he has maintained a website at www.turing.org.uk to enhance and support his original work.”

It takes a while to read this nearly 700 page biography, but it is time well spent. Certainly at a time when issues such as net neutrality are extremely important. In fact, yesterday the Federal Communications Commission ( FCC) in USA “voted on Thursday to regulate broadband Internet service as a public utility, a milestone in regulating high-speed Internet service into American homes. …The new rules, approved 3 to 2 along party lines, are intended to ensure that no content is blocked and that the Internet is not divided into pay-to-play fast lanes for Internet and media companies that can afford it and slow lanes for everyone else. Those prohibitions are hallmarks of the net neutrality concept.” This ruling will have repercussions worldwide. (“F.C.C. Approves Net Neutrality Rules, Classifying Broadband Internet Service as a Utility”, 26 Feb 2015. http://mobile.nytimes.com/2015/02/27/technology/net-neutrality-fcc-vote-internet-utility.html?_r=0 )

Alan Turing and his contribution to modern day technology continues to be relevant even 60+ years after his death.

Andrew Hodges Alan Turing: The Enigma Vintage Books, London, 1983, rev 1992, with rev preface, 2014. Pb. pp.750. £ 8.99

27 February 2015