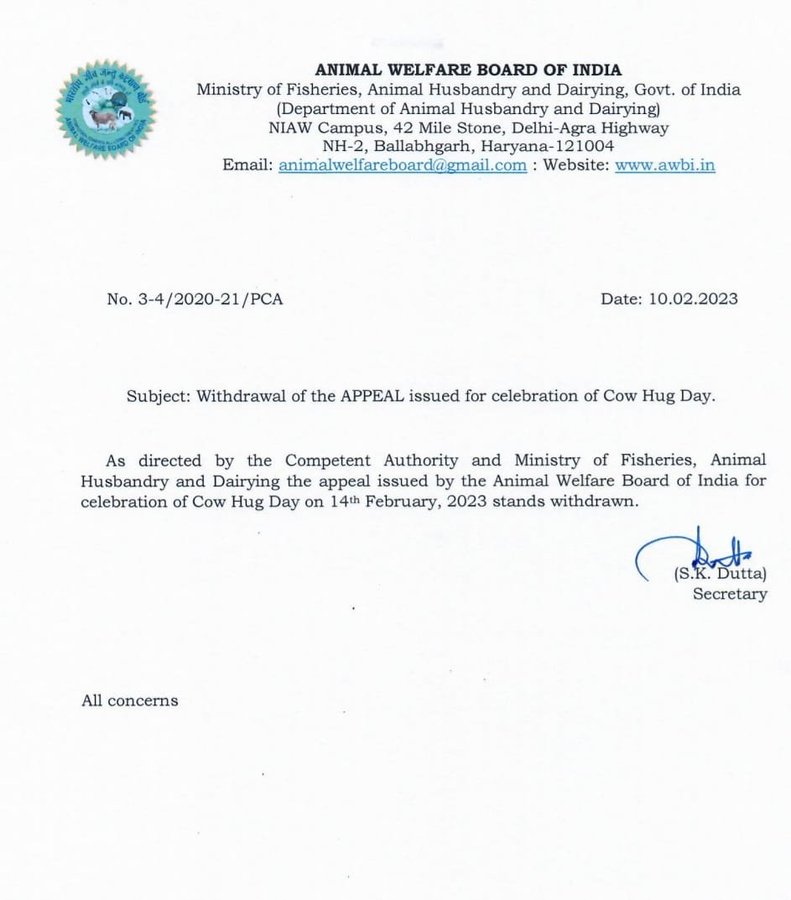

( Aleph sent me an advance reading copy of Saad Z. Hossain’s debut novel, Escape from Baghdad! Upon reading it, Saad and I exchanged emails furiously. Here is an extract from the correspondence, published with the author’s permission. )

I read your novel in more or less one sitting. The idea of Dagr, an ex-economics professor, and Kinza, a black marketeer, make a very odd couple. To top it when they discover they have been handed over a former aide of Saddam Hussein who persuades them with the promise of gold if they help him escape from Baghdad is downright ridiculous. But given the absurdity of war, it is a plausible plot too. Anything can happen. Escape from Baghdad! is a satirical novel that is outrageously funny in parts, disconcerting too and quite, quite bizarre. I do not know why I kept thinking of that particular episode of Alan Alda as Hawkeye Pierce and his colleagues trying to make gin in their tent while the Korean War reached a miserable crescendo around them. The micro-detailing of a few characters, inevitably male save for the chic Sabeen, is so well done. It is also so characteristic of war where there are more men to be seen, women are in the background and play a more active role at the time of post-conflict reconstruction. They do exist but not necessarily in the areas of combat. It is a rare Sabeen who ventures forth. Sure women combatants are to be seen more now in contemporary warfare, but it was probably still rare at the time of Operation Desert Storm. Yet it is as if these characters are at peace with themselves, happy to survive playing along with the evolving rules (does war have any rules?), not caring about emotions and learning to quell any sensitivity they had like Dagr remembering his wife’s hand on her deathbed.

Saad: Thanks for the kind words, and for getting through the book so fast. Aleph has been amazingly easy to work with, they are clearly good people 🙂

JBR: Why did you choose to write a novel about the Gulf War?

When I started writing this, it was before Isis, or Syria, or the Arab Spring. The Gulf War was really the big war of our times, and looking back at Iraq now, I feel that it still is. I wanted to tell a war story, and the history of Baghdad, with all the great mythology, and just the location next to the Tigris and Euphrates was really attractive. I think I started it around 2010. I wasn’t very serious about it at first. The book was first published in Dhaka in 2013 by Bengal Publications.

According to an interview you did with LARB, you never went to Baghdad, and yet this story? Why?

I wrote the story as more of a fantasy than an outright satire or war history. For me, large parts of it existed outside of time and logic. Much of it too, was set in closed spaces, like safe houses and alley ways, and this was just how it turned out. In the very first chapter I had actually envisioned a sweeping, circuitous journey from Baghdad to Mosul, but I couldn’t even get them past two neighborhoods.

But isn’t that exactly what war does to a society/civilization?

Yes, that’s why I prefer using fantasy elements/techniques to deal with war itself. The surreal quality represents also the mental state of the observer, who is himself altered by the horrible things he is experiencing. I’m also now beginning to appreciate the long term after effects of war on a population’s psyche. For example Bangladesh is still so firmly rooted in the past of our 1971 War, almost every aspect of life, including literature is somehow tied to it. The damage is not short lived.

Bangladesh fiction in English is very mature and sophisticated. Much of it is set in the country itself, focused on political violence, so why not write about Bangladesh? Not that I want to bracket you to a localised space but someone like you who obviously has such a strong and nuanced grasp of the English language could produce some fantastic literary satirical commentary on the present. In India Shovon Choudhary has produced a remarkable satirical novel — The Competent Authority, also published by Aleph.

You are right, of course, Bangladesh is ripe for satire, as are most third world countries. I’m a bit afraid because I want to do it right, and I know that if certain things don’t ring true, I’ll face a lot of criticism at home for it 🙂 Technically, I am still struggling to develop a voice that I’m comfortable with. I need my Bengali characters to operate in a certain way, yet I still want them to be authentic, and plausible. I also rely on mythology and fantasy a lot, and this poses a linguistic challenge. I’ve found that sometimes the flavor of mythology doesn’t really translate very well. Each language has a lot of mythology built into it, like English uses a lot of Norse and Greek mythology, for example in the way the days of the week are named after Odin, Freya, Tue. There are situations where you are trying to describe an Asian fantasy element in English, and it doesn’t quite work. It is necessary, in a way, to rewrite mythology from the ground up, which is a very big job.

Fascinating point. Now why do you feel this? Is there an example you can share?

Well just the word djinn, for example. The English word is genie. A genie is a cute girl wearing harem pants granting wishes to Larry Hagman. How can I get across the menace, the fear, the hundreds of years of dread our people have of djinns? How much space do I have to waste on paper trying to erase the bubble gum connotation of genie? Will it be successful in the end, or will the English reader just be confused? What about a word like Ravan, which has an instant connotation for us, a name like a bomb on a page, but in English, it’s just a foreign sounding word that requires a footnote, something alien that the eye just blips over. For me to convey the weight of Ravan, I’d have to build that up, to recreate the mythology for the reader, to act out everything.

Isn’t the purpose of a writer to disturb the equanimity? Will there be a second book? If so, what? Btw, have you read The Black Coat by Neamat Imam?

I haven’t read it. I just googled it, it looks good, I’m going to find a copy. There isn’t a second book, this was not designed to have a serial, the ending is left open to allow the readers to make their own judgments for the surviving characters. I am writing a second novel on Djinns, which is set in Dhaka, so I hope to address some of the issues facing us there.

The story you choose to etch is a fine line between a dystopian world and a war novel. Is that how it is meant to be?

Yes, in my mind there is not one specific reality, but rather many versions which exist at the same time, and if we consider war as a pocket reality, it would certainly reflect a very dystopian nature. While we do not live in a dystopia, there are certainly pockets of time and space in this world which very strongly resemble it.

It is particularly devastating to consider a people who believed in economics, and GDP growth, education, houses, mortgages, retirements and pensions to suddenly be pitched into a new existence that has neither hope, nor logic, nor any use for their civilian skills.

True. I often think we are living a scifi life. It makes me wonder on what is reality?

My understanding is that the human brain uses sensory input to create a simulation of the world, which is essentially the ‘reality’ we are carrying around in our minds. This is a formidable tool since it allows us to analyze situations, recall and recalibrate the model, and even to run mental games to predict the outcome of various actions. For a hunter gatherer, the brain must have been an extremely powerful tool, like having a computer in the Stone Age. But at the same time, because these mental simulations are just approximations of what is actually there I can see that reality for everyone can be subtly different, and if we stretch that a little bit, it makes sense that many different worlds exist in this one.

The Indian subcontinent is a hotbed for political nationalism and neverending skirmishes, with peace not in sight. Living in Dhaka and writing this novel at the back of car while commuting in the hellish traffic Escape from Baghdad! seems like a strong indictment of war but also builds a case for pacifism. Was that intentional?

War is a complex thing. It’s easy to say that we are anti-war, and for the most part, who would actually be pro-war? I mean what lunatic would give up the normalcy of their existence to go and bleed and die in the mud? Even for wars of aggression, the math often doesn’t work out: the cost of conquering and pacifying another country isn’t worth the consequences of doing so. Yet, for all that, war has been a constant companion of humanity from ancient times. It is, I think, tied into our pack animal mentality. The very quality which allows us to freely collaborate, to collectively build large projects, is the same thing which leads to organized violence as a response to certain trigger situations. I believe that the causes of wars have all been minutely parsed and analyzed, broken down into the actions and motivations of different pressure groups, but all of this still does not explain the reality of battalions of ordinary people willing to strap on swords and guns and armor and commit to slaughtering each other. That willingness is a psychological problem for the entire human race to contend with, I think.

JB: As long as you raise questions or leave situations ambiguous, forcing readers to ask questions about war, the novel will survive for a long time.

The creation of old women especially Mother Davala are very reminiscent of those found in mythology across the world. It is an interesting literary technique to introduce in a war novel.

Mother Davala is one of the three furies of Greek myth, the fates whom even the Gods are afraid of. They are also in charge of retribution, which was apt for this particular scenario. This was one of the things I was talking about earlier, with the mythology built into the language. The Furies have such a resonance in English, such a long history in literature, that they carry a hefty weight. I could have used, instead, someone like Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love and conflict, but that name has no real oomph in English, and so it would be a wasted reference.

So if you find it challenging to work mythological elements from other cultures into your fiction, how were The Furies easy to work with?

I think the challenge is to use non English mythology while writing in English. English mythology kind of covers Norse, Greek, Arthurian, as well as Christian mythology, of course. To use elements of any of those is very easy because there is a lot of precedent, and the words already exist in the lexicon. The problem arises when you are writing in English about a non western culture. Then you are forced to describe gods, goddesses, demons, etc, which sound childish and irrational, because they have no linguistic resonance in English. If I say the words Christ and crucifixion, there is an instant emotional response from the reader. If I describe the story of the falcon god Horus who was born in a strange way from his mother Osiris, and performed magical acts in the desert and then eventually died and returned to life, it just sounds quaint, and peculiar.

Have you written fiction before this novel?

I’ve been writing for a long time, since I was in middle school, and my earlier efforts have produced a vast quantity of bad science fiction and fantasy. It started with a bunch of friends trying to collaborate on a story for some class. We each picked a character, and made a race, history, etc for them. The idea was to create a kind of mainstream fantasy story. I remember we all used to read a lot of David Eddings back then. The others all dropped out, but I just kept going. Writing a lot of bad genre fiction helps you though, because you lose the fear of finishing things, plus all that writing actually hones your skills.

How long did it take you to write this story and how did you get a publication deal? Was it an uphill task as is often made out to be?

I took a couple of years to write this. It started when I joined a writers group, and I had to submit something. That was when I wrote the first chapter. The group was very serious and we had strict deadlines, so I just kept writing the story to appease them, and then I was ten chapters in and growing attached to the characters, so I decided to go ahead and finish it. This was a group in Dhaka, it was offline, we used to physically meet and critique stuff. A lot of good work was published out of that. It’s definitely one of the critical things an author needs.

Publishing seemed impossibly daunting at first, but when it happened, it was easy, and through word of mouth. I knew my publisher in Bangladesh, and when they started a new English imprint, they were looking for new titles, and I was selected. Some of my friends knew the US publisher, Unnamed Press, and I got introduced, they liked it, and decided to print. Aleph, too, happened similarly. You can spend years querying and filling up random people’s slush piles, and sometimes things just happen without effort. My philosophy is that I am writing for myself, with a readership of half a dozen people in mind, and I am happy if I can improve my craft and produce something clever. The subsequent success or failure of it isn’t something I can necessarily control.

Saad Z Hossain Escape from Baghdad! Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2015. Pb. pp 286. Rs. 399

28 August 2015