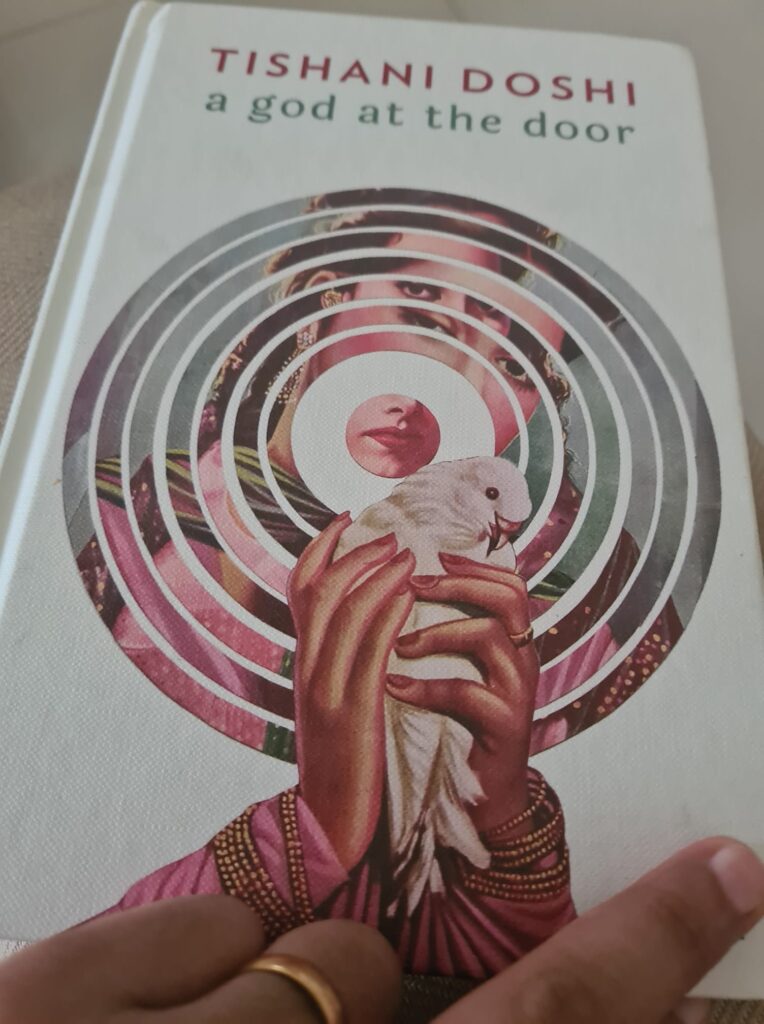

Tishani Doshi’s “A God at the Door”

Today, my eleven-year-old daughter woke up much earlier than her usual time. She had had a nightmare. She dreamt that she was in 1939 Nazi Germany. She was in a classroom and then opened a door to go elsewhere. Then, to her horror, she was packing her precious belongings and needed to run. She did not know where she was running but she was and she was terrified. While narrating the incident, she looked alarmed and began wringing her hands in nervous fear. She kept using the collective pronoun “we”, but when asked over and over again, who else was with you, she finally admitted to the singular “I”.

The trigger for this dream in all likelihood have been the books and documentaries about World War Two that she has immersed herself in. She recently read a YA novel, based on a true story, of a Catholic girl who saved a family of thirteen Polish Jews. And much else. Much of it is driven by interest and partially by her school curriculum.

The point of this anecdote is that Art is powerful. It serves multiple purposes. If employed correctly, it operates more than Art for Art’s Sake. Most importantly, it allows the artist to use their creative sensibilities to observe, record, comment and preserve events in collective memory, lest we as a race forget the horrors that have been perpetrated.

Poet Tishani Doshi’s latest collection A God at the Door ( HarperCollins India) serves this purpose admirably. The seething rage and at times, a sense of helplessness, that she feels as an individual witnessing the systematic violence, communalism and the boxing in of women into their homes, are noted in her poems. “The Stormtroopers of My Country” that is an ode to the decimation of a beautiful country is extremely powerful. It is a country that will vanish rapidly if we allow it to happen. The poem ends with a firm belief in our abilities to survive the most violent of assaults.

with the pogrom atrocity death march love

march no such thing as a clean termite to burn

is to purify oh our culture so ancient so good

we’re in the thick of the swastika now no brow

beating will divide us together we must stick

The importance of the artists and writers in turbulent times can never be under estimated. They have the immense ability to imprint searing words upon the reader’s mind that are hard to shirk. Such as:

History too has a hard time remembering

the black waters they crossed, …

…History tries not to be sentimental,

although letters give things away.

( “Many Good and Wonderful Things”)

Or

There comes a point in the battle

when the last international watchdog

is forced to leave the country. Reader,

I know you’re prone to anxiety. This

is when it happens. The lagoon, the ambush,

Bullets raining down in a no-fire zone.

Quick, into my echo chamber.

( “Instructions on Surviving a Genocide”)

Or

… I found a village, a republic,

the size of a small island country with a history

of autogenic massacre. In it were all our missing women.

They’d been sending proof of their existence —

copies of birth and not-quite-dead certificates

to offices of the registrar.

What they received in response was a rake

and a cobweb in a box.

(“I Found a Village and In It Were All Our Missing Women”)

Or

Forget where you came from, forget history.

It never happened, okay? We need soldiers on the front line.

Of course we can coexist. We say potato, they say potato.

We give them their own ghetto.

(“Nation’)

Or

Say the words ‘Bay of Bengal’

and ‘Buchenwald’ one after

the other, and they sound

beautiful, just as ‘landfills

does. And then imagine it:

(“Do Not Go Out in the Storm”)

The poems in this collection are crying to be performed by multitudes of people. There is no other way to describe this but there seems to be a strong force at the core of these poems that is urging the reader to read these out aloud and share them with more and more people. It is as if when read out aloud, the truth these words enshrine will hit home hard and perhaps embolden us to push back. It is an incredible experience to read poetry that much of the time is a wail of pain and anger intermingled and yet gets transferred seamlessly to the reader and co-opt them into this collective grief. The desire to act can only happen if the personal will is strong enough to turn it into a political act. Perhaps by immemorialising contemporary events, the poet urges a mass awakening to fight against the ills.

My head hurts. And yet I find myself going over and over and over these poems. Soon, my daughter will be able to read and understand these poems. I hope she does. I hope she will convey them to her peers and in time, future generations. These poems/stories/ moments-in-history should not be forgotten.

Read A God at the Door.

I urge you.

8 August 2021