Interview with Armenian author Lusine Kharatyan

(C) EU

This interview is facilitated by EUPL and funded by the European Union.

I am posting snippets of my correspondence with Lusine as it would give readers an insight into how well-crafted her pieces are.

Dear Lusine,

I read your articles. It has taken a while to assimilate your incredibly powerful writings. On the face of it, these are simple articles and observations, but if I try to read it slowly or even try and emulate your writing style, it is challenging. It is almost as if you have thought through every word used, every sentence written, and the arrangement. It happens in any piece of writing but in yours it is almost as if to give the reader some sense of the feeling of dislocation that you have probably experienced. Almost as if to create a shared empathy without any sentimentality seeping in, but merely to understand the situation.

It has been a few days since I read your articles but I could not bring myself to compose the questions immediately. When I finally did, I found myself in the midst of an unusual task. I transcribed each question at least three times even if it were being copied without any changes. I am still unable to understand this act of mine except to say that it is your writing that moved me tremendously. I wanted to strike the right tenor while formulating the queries.

Dear Jaya,

Thank you! It took me a while to answer your questions, as you definitely did your “homework” very well and each question invited a long conversation. Anyway, I tried to be short, but feel free to ask more questions if anything is not clear.

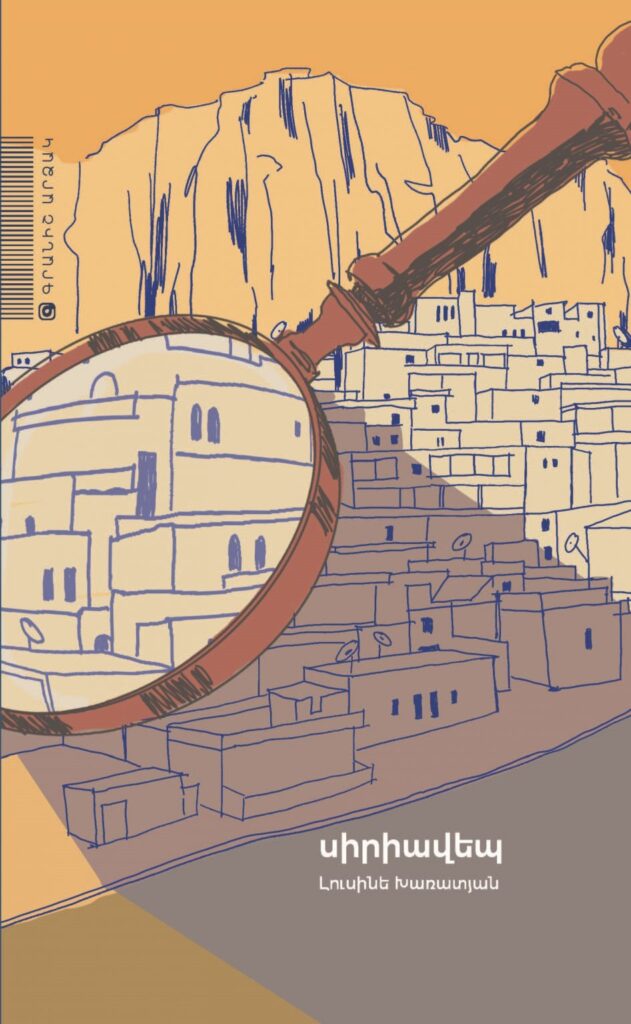

Lusine Kharatyan is a Yerevan-based writer and cultural anthropologist. Born and raised in Soviet and post-Soviet Armenia, she lived and studied in different parts of the world, including Egypt and the USA. Her writing is significantly influenced by her anthropological research, fieldwork, and travels. Kharatyan’s first novel ծուռ գիրք (The Oblique Book), was published in 2017. Her second book, collection of short stories Անմոռուկի փակուղի (Dead End Forget-me-not) was published with a monetary prize from the First Yerevan Book Fest, and shortlisted for the 2021 European Union Prize for Literature. In 2019, Kharatyan was awarded a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of Armenia for writing her second novel, Սիրիավեպ (A Syrian Affair), which was nominated from Armenia for the same prize in 2023. Lusine’s short fiction has been published in English and Georgian, including her own translations of #America_place from 9/11 to 11/9 and #America_place Pregnant published at Asymptote site for world literature in translation.

Kharatyan holds a master’s degree in Public Policy from the University of Minnesota (2004), a Diploma in Demography from Cairo Demographic Center (2000), and a Diploma of higher education in History/Socio-cultural Anthropology from Yerevan State University (1999). Since 2018, Kharatyan is a member of the Committee of Experts of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. She is a member of PEN Center Armenia and the Chair of its Women Writer’s Committee since 2021.

Q1. You are bi-lingual. Do you translate and change the text when writing or translating from Armenian into English?

I would not say I am bi-lingual. Well, sometimes it feels like I live in three languages, also visually, as all three use different letters- Armenian, English and Russian, but my language is Armenian. While I probably understand Russian deeper and better than English, with almost all possible nuances and in all possible contexts (not only because I was exposed to it since childhood and also studied it as a second language at school, but also because Russian was the language of the literature I read during my formative years) I am not sure that I can write in that language, as I haven’t practiced writing in Russian since the 1990s. Also, I do not feel comfortable speaking and/or writing in Russian to native Russian speakers, as there is always some feeling of ‘inferiority’ or rather impediment/disability involved in using the language of the colonizer while speaking to the colonizer. I do not feel that I am able to express my thoughts at an equal level, hence I prefer communicating in English with native Russian speakers, so as we are at equal terms. With English, I do not have a similar feeling, as I do not share a similar history with native English speakers, who are probably “The Colonizers” for Bharat (…if I get it right one of the reasons to change India’s name into Bharat was to get rid of the remnants of that colonial past). So, our relationship with a language is always very context-specific and has all the burden/weight of both collective and personal experience/memory and power dynamics involved. I remember, for example, when I was first reading Platonov’s The Foundation Pit, of course in the original language, I kept thinking whether it would be possible to translate his unprecedented style and language with all the nuances, and particularly the bureaucratic and/or power’s language used in very unexpected contexts and places into Armenian. I was not sure that Armenian had the same capacity and richness, given that it was not the language of the conventional “power” or authority. However, after several attempts at translating some passages I was surprised how well it was possible to not only find appropriate words and phrases, but also to convey the very tone and style. This encouraged me to translate my own texts. When translating, you always have to make difficult choices, sometimes maybe to give up on style or tone, or preciseness, sometimes to invent words. And as I am not a native English speaker, I am not always sure whether my translation really delivers what the Armenian text is saying. I am usually trying to stick to the original as much as possible, but sometimes I feel that it is at the expense of the style or the language quality, and at times it feels like writing a new text. Interestingly, it is much easier to do so in English, as it seems more democratic or tolerant towards non-native speakers, given that it is the most spoken/widely used language in the world. Or maybe it is because I do not have the same level of proficiency in English to notice all the nuanced mistakes that I make. However, until now I have not dared to translate texts, which are very context-specific, which are entrenched in the context, since I am not sure that I can translate the context without too many footnotes, so that it would make sense and still have the same depth and layers, and at the same time would keep the lightness of the language and style.

Q2. Is being sensitive to cultural sensibilities an important consideration to your writing? Or is it that the art of communicating in a nuanced manner is appreciated more?

Being sensitive to cultural sensibilities is in general a very important aspect of me. I believe anthropology is first of all a way of life, and not a profession. This way of life also implies not only being sensitive to different cultures, but generally respecting and accepting them as they are, without imposing your own. At the same time, you can’t stop doing autofiction, since ethnography, or participant observation is always switched on in you, and you keep walking through your life having that internal camera or a reading glass looking at everything around you, including yourself, from somewhere above. You are a participant and an observer at the same time. Sometimes you wish you could actually be more participant than an observer, to feel more or deeper, and that this “observer” part of you would keep the feelings on hold, but then you fictionalize and it somehow helps with not only reflecting but also feeling and finding others who share your feelings and who are eager to borrow your lenses. It is some kind of an effortless stream of conscience that flows into literature. This is where you also try to communicate in a nuanced manner, but then you find yourself stuck in orientalism and you either try to also “orientalize” the protagonist or the author, so as to be at equal terms, or to rewrite the text. By default, I always have these lenses in whatever I do. This allows multi-perceptivity and makes the text to look and read like an effortless flow; which is at the same time richer, multi-layered and more nuanced. However, sometimes I intentionally try to put these lenses aside, so as the text is not perceived as “censored” or “politically correct”, but has all the roughness and some touch of supposed “sincerity” or expected “honesty.” Yet, it does not always work, as this type of honesty means dishonesty to myself, because that is not the way I see the world, that is not who I am, and I prefer my text being vulnerable, more nuanced and sensitive to cultural sensibilities.

Q3. How challenging is it for a cultural anthropologist to write fiction?

Well, as mentioned, anthropology is a way of life for me. On the one hand that way of life greatly helps to find themes and topics, times and places, issues and protagonists, human stories, dramas and comic situations for writing. But it also brings some challenges․ One of the main challenges is probably the ability of putting the researcher aside and finding a different frame and language to tell the story. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. And the same happens the other way around, when the writer in me gets stronger than the researcher.

Q4. Is it possible to define terms such as identity, ethnicity, home, & community? In the few examples of your writing that I read, I got the sense that you were exploring these terms without casting them in stone. To my mind, these are fluid as in “ever evolving” concepts, but what do they mean to you?

I have a friend who kept saying that every time she was asked to present herself, the very first thing she would tell was that she was Armenian. This is how strong she felt about her Armenian identity. But then I asked her once, whether she would do the same when presenting herself to an Armenian in Armenia, or was that when she would present herself to foreigners or someone from the diaspora whom she met abroad. She was surprised by my question, and after a bit of thinking answered, that this was probably when she would present herself to foreigners or diasporans abroad. Then she thought more and said that in Armenia it always depended on the situation and the people she presented herself to. In some cases, she would say that she was a teacher, in other cases she would first refer to the district of Yerevan where she grew up, yet in some circumstances she would speak of her workplace or where her parents came from. And she went on and on, until she ended up counting around 10 different identities, as we agreed to call those “ways of presenting herself.” Thus, depending on the situation and context, one of our identities can become more active than the others.

While the researcher in me understands and knows that there are people/societies/cultures where the identity/ethnicity/belonging is still perceived as something homogeneous, rigid, solid and cast in stone, I do believe that this kind of understanding is self-deceiving, as a person living in our post-Hiroshima, post-Gagarin, post-man-on-the-moon, post-cold-war, post-modern, post-industrial, post-post-post, patchy and fragmented world of AI and digital reality cannot pretend or afford to have this clear-cut homogeneous identity. We should simply accept our fragmented, fluid, ever-evolving and spongy identities and try to live with them in peace, without a multiple personality disorder. And most of my writing is as fragmented and patchy in terms of style, themes, plots and genre as our identities are.

Q5. What is it that you seek in women’s writing? As a woman writer, what is it that you wish to convey or gender distinctions are immaterial?

Gender identity is one of the most active and vibrant identities we have, and I always look for that perspective in women’s writing. I want to see the world also through those lenses, as we have been deprived of this opportunity for ages. When writing, I do not put a special effort to convey things from a woman’s perspective, but since being a woman is an important part of me, it is unavoidable and is reflected in my writing. There is this stereotypical thinking in the Armenian literary circles that the literature crafted by women is “weak” and “shallow”, that only men can write “strong” literature. Many from the generation of women writers before mine tried to “conceal” their gender identity by writing texts which would be as much like the texts of their male counterparts as possible, so those texts would be perceived as “strong” pieces of literature. Some were even proud when critics wrote and spoke that they “have a male pen”, or that “their writing is so strong that it is not possible to understand that the writer is a woman.” Fortunately, that is changing and we now see more women writing very sophisticated, rich, deep literature without mimicking “male” texts.

Q6. What is the OH project mapping memories from Armenia and Turkey about?

This was a very important and defining project for me. Actually, my first novel, ծուռ գիրք, was inspired by it. I do not know how aware are your readers of Armenian-Turkish relations, so for those who do not know much, probably some background information is necessary. At the beginning of the last century Armenians used to mostly live in their ancestral homes on the territory of two empires, Ottoman and Russian. We, Armenians, call the part of historical/ancient Armenia, which is now on the territory of current-day Turkey, Western Armenia, and the part that constitutes the current-day Republic of Armenia and some other territories are called Eastern Armenia. Thus, what would be Armenians’ homeland was divided between Russian and Ottoman Empires at the time of World War I. With the rise of national-liberation movements in the 19th century, and particularly on the territory of the Ottoman Empire, Armenians living there also started demanding more rights and freedoms. To these demands Ottoman authorities responded with several Armenian massacres in the late 19th– early 20th century. When the WW I broke, the new Ottoman Government of Yung Turks decided to get rid of the “Armenian Issue” through organizing the first Genocide of the century, where over a million Armenians were marched to death, burned in their homes or churches, slaughtered and massacred. Most surviving Armenians spread all over the world, forming diaspora communities. Some of the survivors found refuge on the territory of the current-day Republic of Armenia, then- the Russian Empire. Today, a century after the events, Turkey still denies the Genocide, while for the Armenians this is a defining trauma, a master narrative which greatly influences our identity. So, the project you ask about was trying to plant some seeds for Armenian-Turkish reconciliation through oral history and adult education. The idea behind was that through collecting oral histories about a particular location on the territory of nowadays Turkey where Armenians used to live before the Genocide from both sides of the border, i.e. at the place itself and among the Genocide survivors originally from that place who now live in Armenia, we can create the history of the place as it is remembered, narrated and imagined today. One of the outcomes was the book “Moush Sweet Moush: Mapping Memories from Armenia and Turkey”, where in the introduction we state the following: “Even though we have included a brief factsheet on the history of Moush focusing on the area’s cultural significance for Armenians and some statistics from the beginning of the 20th century, we do not intent to present the local history of Moush as a set of facts, a definite truth about the place or events that happened in that place. In a sense Moush is a discourse in this book. We are not simply presenting its history. We are presenting the place as it is remembered, imagined and narrated in Turkey and in Armenia. We do not want to define, describe or locate Moush politically, administratively or historically. We do map Moush, but not as politicians or official historiographers do. We map it through people’s narratives and our group experience. While current political maps with their defined borders interfere with this discourse, we believe that they do not dominate mental maps of people.”

Q7. How instrumental was the covid pandemic in opening up memories and thus, presumably, impacting your writing?

There is probably no person in the world that was not impacted by the Covid pandemic. For me, as much as it opened a door for memories, it also helped with reflection, as due to the isolation you have more time for thinking and reflection, which nowadays is a luxury. At some point I started posting daily photos on my Facebook early in the morning. Over time, these early coffee/tea “good mornings” became very popular among my Facebook friends and beyond. They became a kind of “safe space” for “sharing and caring,” and were collected in an album Isolator #1. Eventually, I was invited to organize a photo exhibition in one of the galleries in Yerevan. The poster of the exhibition was the last photo from the album, where you see an upside down coffee cup (with small coronas/crowns on the cup) looking for a coffee fortune reader, thus ending the entire period with a question mark. And the answer was quick to come: we opened the exhibition on the evening of September 26, 2020, and woke up to the war next morning on September 27, 2020, learning that Azerbaijan had attacked Artsakh/Nagorno Karabakh. The Covid isolation ended in the 44-day-war. This isolation and the process of me posting on Facebook was also reflected in a short piece of writing, The Summer of Chomalag, written before the war. However, as every story in our Netflix-era world goes on for several seasons, I could not stop there. As the war started, I have received requests from friends and acquaintances to continue with my morning photo-posts as they helped to wake up with a hope for a brighter future. So, I started a second season with a new album, Shelter #1, and my Facebook story-telling experiment triggered by Covid evolved through dialogue and took me to really unexpected places.

Q8. How do you define “maps”? These can be physical as well as mental, rt?

To me the definition is very simple- we are our maps. All these different identities we spoke about earlier are as much mapped in our minds and very bodies, as they are on the body of the earth. Sometimes I even visualize people moving in space and time taking their maps with them and making those maps bigger. Those are endlessly elastic. However, as much as they widen and enlarge, they can also get narrower and smaller, up to a size of a dot. A more inclusive identity means a bigger map. The narrower gets your map due to war, limited right to movement because of inequality, social injustice or simply being born in a part of the world that does not allow you much movement, your inability to see the world bigger due to illiteracy or lack of access to different carriers of information, or due to the narratives you grew up with, the grimmer and slimmer gets your world. In one of my short pieces, #America_place from 9/11 to 11/9, the protagonist first time in her life sees a map drown differently than what she is used to, an America-centered map. And it is only then that she realizes that the way she sees the world very much depends on where she is physically located. It is very bodily and also mental experience at the same time. Also, our mental maps consist not only of places and names of geographical locations, but of people and our connections. I have never met you, but you are already on my map, and when I think of India now, I already think of a bit different India, India that has Jaya in it.

Q9. What is it about making lists that appeals to you as a writer and as a custodian of cultural memories?

Lists are how you define your map, a deliberate choice of including some things and excluding/dropping other things.

Q10. Do you have any Armenian authors / literary website recommendations for readers?

I’d suggest starting from last years’ Asymptote’s Fall Issue that features Armenian writers in translation. Then they can explore more.

Disclaimer: This paper was written under the European Union Policy & Outreach Partnerships Initiative with the view to promote European Union Prize for Literature awardees. The publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.