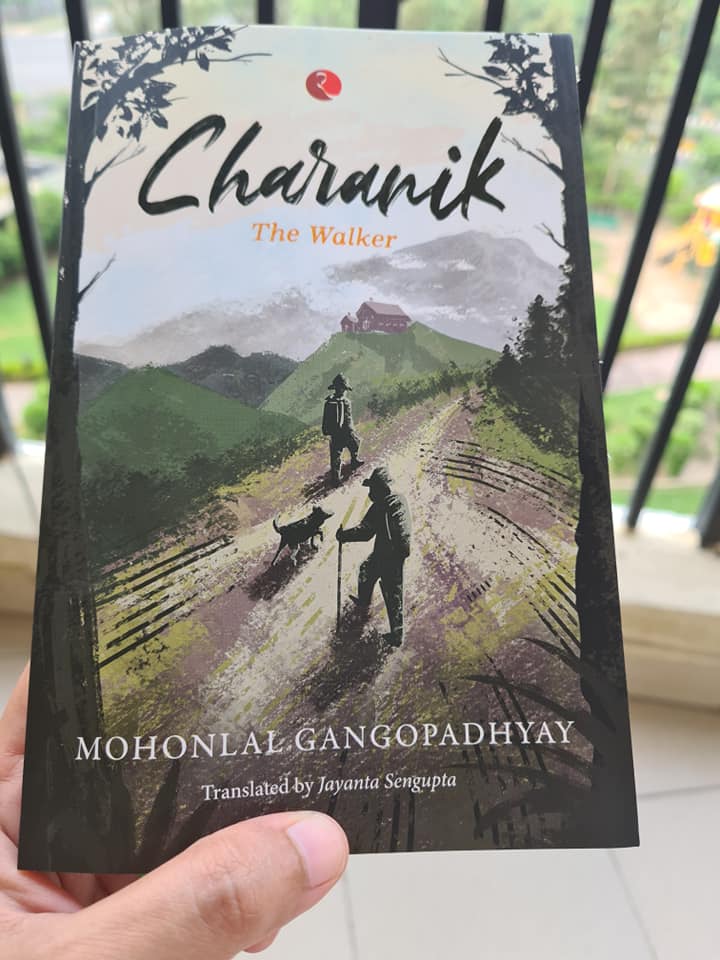

“Charanik” by Mohanlal Gangopadhyay, translated by Jayanta Sengupta

Writer Mohanlal Gangopadhyay’s Charanik: The Walker was first published in Bengali in 1942. It is an account of his walking tour of Czechoslovakia during his summer break in 1937. At the time, Gangopadhyay was studying at the London School of Economics, London. So he was able to plan a holiday in Europe with a friend, Mirek.

Charanik is a lovely, calm, account of these three months. The writer records their stay in various youth hostels or at the home of hospitable peasants. Along with Mirek, he would walk a few hours every day. They visited beautiful valleys, hills, glacial caves etc. They visited local fairs such as at Uherske Hradiste, visited the worle-famous primeval forests of Ruthenia, trekked in the High Tatras, visited the Demanovska Ice Cave with its magnificent stalactites and stalagmites that had only been discovered twenty years earlier, they went looking for Hribis mushrooms, they visited Poprad Lake etc. They lived off the land plucking wild berries, strawberries, apples, bilberries and mushrooms to eat. Using fresh spring or river water to brew hot tea for their soups or tea. Every night, if possible, the duo halted at a youth hostel, where only basic amenities were provided. Yet, it was comforting to a bunch of exhausted travellers. To the writer, carrying a rucksack with essentials on his back instead of relying on a porter or even halting at these hostels was a steep learning curve as he had no clue how to make his bed, fold his clothes or even wash them regularly. He was so used to having staff assist in domestic chores. But it did not deter him. He learned fast and enjoyed the experience.

The book has been translated by Jayanta Sengupta who first read the Bengali edition as a school student. He enjoyed the book so much that when he visited Europe for the first time, he decided to do so with a shoestring Charanik-like budget.

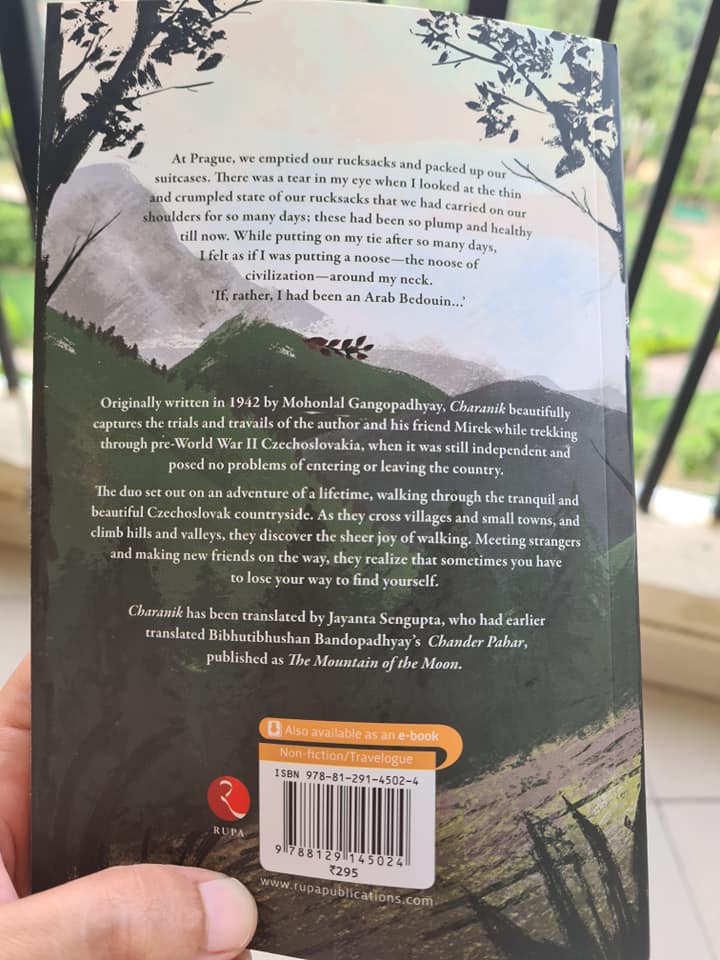

Mohanlal Gangopadhyay came from an illustrious family. His father was the writer Manilal Gangopadhyay and his mother, Karuna, was the daughter of Abanindranath Tagore. Surprisingly, the writer chooses in this book to not mention anything about Adolf Hitler, who was already in power in Germany. Nor that the Germans in Czechoslovakia were demanding the right to autonomy, which led directly to the Munich Pact being signed between Hitler and Neville Chamberlain in September 1938; as a result, parts of Czechoslovakia would be handed over to Nazi Germany. Despite meeting people every day at the youth hostels, mostly walkers and trekkers like themselves, Gangopadhyay never mentions politics. Instead his descriptions are idyllic. Incredible to think that he had the ability to spend pages describing streams, mountains, forests, views from mountain tops and the unfortunate events of being caught in a sudden freezing downpour, in the middle of nowhere. But as the translator points out that now the map of Czechoslovakia has changed drastically over the past few decades. For one, the Czech Republic and Slovenia are independent nations. Ruthenia had not really existed as an independent nation. Many of the other places referred to in the book can now be found in the maps of Hungary, Poland, Ukraine and other countries.

Charanik is a soothing book to read. It has been translated beautifully. There is a gentle pace to the narrative that is very calming. It is illustrated with black and white photographs taken and sketches made by the author’s wife, Milada Ganguli.

Read the book.

12 June 2021