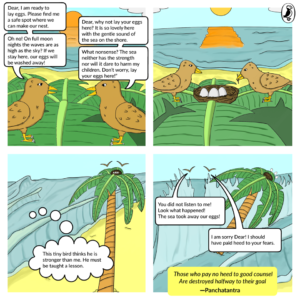

( Puffin India has recently released a new translation of Panchatantra translated from Sanskrity by well-known writer Rohini Chowdhury. Reproduced below with the author’s permission is her essay included in the book on why she translated these beloved tales. Here is a lovely trailer for the book released by the publishers, Penguin Random House India. They have also illustrated some of the stories as cartoon strips.)

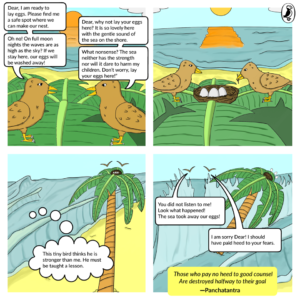

( Puffin India has recently released a new translation of Panchatantra translated from Sanskrity by well-known writer Rohini Chowdhury. Reproduced below with the author’s permission is her essay included in the book on why she translated these beloved tales. Here is a lovely trailer for the book released by the publishers, Penguin Random House India. They have also illustrated some of the stories as cartoon strips.)

Those who pay no heed to good counsel are destroyed halfway to their goal.

The fables of the Panchatantra have always been a part of the landscape of my life, and so, when my daughters were born and grew old enough to listen to bedtime tales and ask for them, these were amongst the first stories I told them. It was in searching for more Panchatantra tales for my daughters that I realised the absence of a complete translation for children, and one that maintained the structural integrity of the original work. Now, one of the most interesting features of the Panchatantra is its story-within-a-story structure – stories contain stories, which contain more

One who anticipates disaster and plans ahead, survives and lives a long happy life

stories, somewhat like a Russian matryoshka doll that contains doll within doll within doll. In every translation and retelling that I could find, though the stories had been charmingly retold and often beautifully illustrated, they had been presented as stand-alone tales without the context or frame-story within which they occur in the Panchatantra. This, I felt, took away from the tales substantially. I therefore decided to translate the complete Panchatantra myself, keeping intact its original form and structure.

The translation went much slower than I had expected; the children

The one who gives a stranger all his friendship while forsaking his own kind, meets an unhappy end.

grew much faster and had soon outgrown these tales. So, for many years, I put this translation aside and became busy writing and translating other books – till a conversation with Puffin India in July 2015 brought me back to it. I looked at the Panchatantra again, with different eyes, and realised its true significance: not only was it a masterly treatise on politics and government and a manual for conducting our daily lives with wisdom and common sense, but devised to educate the three foolish sons of a king in the ways of the world, it was also a revolutionary, and successful, experiment in teaching young people. Where traditional methods had failed with the princes, the fables of the Panchatantra succeeded – by teaching them practical wisdom, and by awakening in them a curiosity about the world. Within six months, the blockhead princes had become wise and knowledgeable young men. Since then, says the Panchatantra, its stories have been used to educate young people everywhere, a claim that is borne out by the many translations and retellings of this work that are found all over the world, even today.

We know very little about the author of the Panchatantra, except what the introduction to the work itself tells us – that his name was Vishnusharma, that he was a Brahman, exceptionally learned, a renowned teacher, and eighty years of age at the time he composed this work. Since we have no other evidence regarding Vishnusharma, it is difficult to say whether he really was the author of the Panchatantra or himself a fictional character, invented as a literary device for the purpose of narrating the stories. Some versions of the Panchatantra – from southern India and South-east Asia – give the author’s name as Vasubhaga. Again, there is not enough evidence to confirm his identity or his existence.

The original Panchatantra is in Sanskrit, and has been written in a mixture of prose and verse, in a style that is simple and direct. The work is divided into five parts (hence the name: pancha: five and tantram: parts), each part dealing with a particular aspect of kingship, government, life and living. The stories are narrated mainly in prose, but the lessons derived from the tales are usually given in verse form. The Panchatantra’s ‘story within a story’ structure—individual stories are placed within other stories, and each individual part or tantra replicates the structure of the work as a whole—serves to keep its audience engrossed as it takes them into a series of stories, deeper and deeper, from one level to the next.

Most of the characters of the Panchatantra are animals that behave, think and speak like humans. In every culture across the world, people have given human characteristics to animals. But the qualities that people see in particular animals vary across cultures. Thus, an owl is considered wise in England, but evil and unlucky in India. The animals of the Panchatantra conform to the ideas held about them in Indian culture. So, a heron is regarded as deceitful and cruel, for he stands still for hours on one leg pretending to be an ascetic doing penance when we all know that he is actually waiting to grab the next unwary fish that swims too close. Similarly, an elephant is noble and proud, a jackal is greedy and cunning, and a lion, though the king of the animals, is arrogant and often easily fooled by a weaker, more intelligent animal. An ox is loyal, a dog is unclean and greedy, and a cobra dangerous and untrustworthy. The audience for which the stories of the Panchatantra were meant would have known these qualities of particular animals, and so would have known instantly what to expect of them in the stories.

The author of the Panchatantra has used one more device to make it easy for his audience to understand the nature of his characters, and that is their names. He has given his characters, whether human or animal, names that highlight certain aspects of their appearance or behaviour, or give insights into their nature. Thus we have Pingalaka the lion, whose name means ‘one who is red-gold’, named for his fiery coat, Dantila the jeweller whose name means ‘one who has big and projecting teeth’ and immediately gives us a vivid image of the man, Chaturaka the wily jackal whose name means ‘one who is sly and cunning’, and Agnimukha the bedbug, whose name means ‘fire-mouth’ and almost makes us go ‘ouch’ as we imagine his bite!

The appeal of the Panchatantra is not limited only to the young. Apart from its wonderful stories and ageless wisdom, it is a work that looks at life head-on. Rather than seeking to present linear solutions where good wins over evil, moral behaviour wins over the immoral or even amoral, it acknowledges that life, love and friendship can be complex, that politics, government, human interactions are not always straightforward, and even right and wrong, truth and falsehood can often be a matter of circumstance, expediency, or what is practical.

As a result, the stories of the Panchatantra became immensely popular, and travelled across the world – in translations, or carried by scholars, merchants, and travellers. Even today, the tales resonate with people of all ages, at different levels, in different ways, everywhere. In its Arabic translation, the Panchatantra became famous as Kalila wa Dimna (after the names of two of the principal characters, the jackals Karataka and Damanaka); in Europe it became known as the Fables of Bidpai. Many of the stories of the Panchatantra can be found in the fables of La Fontaine in the 17th century, and their influence can be seen in the stories of the Arabian Nights, as well as in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. The stories also travelled to Indonesia in both oral and written forms. Today there may be found more than two hundred versions of the Panchatantra across the world, in more than fifty languages. The oldest recension is probably the Sanskrit Tantrakhyayika from Kashmir; this predates the Panchatantra version available to us today. The most famous retelling of the original work is the 13th century version by Narayana, known as the Hitopdesa.

My translation, a labour of love for my daughters, is my attempt to make this great work available to the young people of today.

Rohini Chowdhury is an established children’s writer and literary translator. Her books can be bought on Amazon.

Copyright © Rohini Chowdhury, 2017.

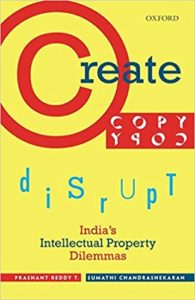

It is befitting to mention Create, Copyright and Disrupt: India’s Intellectual Property Dilemmas by Prashant Reddy T. and Sumathi Chandrashekharan. The title itself a play on the slogan “Create, Protect, Innovate” that has been adopted by IP agencies and IP conferences worldwide. It gives a good overview on the patent history in India particularly for the pharmaceutical industry, the impact of the Berne Convention the publishing industry in India to the recent amendment to the Copyright Act ( 2012) brought about at the insistence of ex-Parliamentarian and prominent lyricist Javed Akhtar and finally the Geographical Indications of Goods Act [Registeration and Protection] Act, 1999 illustrated with the famous Neem and Basmati rice cases. The essays are written lucidly with a view to being accessed by the lay person and not necessarily mired in legal speak.

It is befitting to mention Create, Copyright and Disrupt: India’s Intellectual Property Dilemmas by Prashant Reddy T. and Sumathi Chandrashekharan. The title itself a play on the slogan “Create, Protect, Innovate” that has been adopted by IP agencies and IP conferences worldwide. It gives a good overview on the patent history in India particularly for the pharmaceutical industry, the impact of the Berne Convention the publishing industry in India to the recent amendment to the Copyright Act ( 2012) brought about at the insistence of ex-Parliamentarian and prominent lyricist Javed Akhtar and finally the Geographical Indications of Goods Act [Registeration and Protection] Act, 1999 illustrated with the famous Neem and Basmati rice cases. The essays are written lucidly with a view to being accessed by the lay person and not necessarily mired in legal speak.