I interviewed Sugata Ghosh, Director, Global Academic Publishing, Oxford University Press on their newly launched Indian Languages Publishing Programme.

I interviewed Sugata Ghosh, Director, Global Academic Publishing, Oxford University Press on their newly launched Indian Languages Publishing Programme.

Please tell me more newly launched Indian Language Publishing programme? Who is the target audience — academics or general readers? How many titles / year will you consider publishing?

The Indian Languages Publishing Programme was initiated with OUP’s desire to expand its product offerings to an audience whose primary language is not English. OUP’s existence in India as an established academic press spans more than 100 years. In this long span of its existence it has published a pool of formidable authors and widely acclaimed academic and knowledge-based resources. Our only limitation in a diverse country such as ourselves was language –– though we have been doing the dictionaries and in other Indian languages. In a glocalized world however, limiting ourselves is not an option. As readers change, so should publishers. The increasing demand for resources in Indian languages is not so new; the changing economic and socio-political climate has long been the harbinger of this change. Today we are only heeding its call by beginning publications in these languages. In the first phase of the programme, we have shortlisted two major Indian languages Hindi and Bengali, and a basket of our classics for translation into Hindi and Bengali. We aim to hit the market with 12 such titles by January of 2018. Our target is around 15-20 titles per year to begin with.

Does this imply it is a separate editorial team? Will you have in-house translators? Over time will the list expand to include contemporary stories from regional languages?

We currently do not have any extra resource helping us with the programme. We plan to have new editorial members for both the languages, they will be on board by next year, depending on how well the programme takes off. We do not plan to have in-house translators. We are only working with freelancers and individuals and plan to do so in the future. We might collaborate with other publishers to help seek translators and develop the translation programme further. We have no plans of expanding into fiction at the moment. We are sticking to non-fiction, academic, and general interest titles.

The first phase is of course translation heavy as we begin to establish ourselves in the market, however, there are new acquisitions currently underway for the coming years. As the programme develops, a healthy mix of translations and new books in Indian languages will be made available in both print and digital formats. While beginning with these two languages were accessible, given our resources, our long-term plan is to venture into new Indian languages such as Tamil, Telugu, Marathi etc. For now we are taking one step at a time to build this programme with the mature languages. When the time comes to include new languages, we will do so.

Our core audience remain the same as our English language books, mostly students, teachers, scholars, researchers, civil society activists, think tanks, as well as general readers. While researching the market for Hindi and Bengali books, we realized that reading habits differ from one to the other. While the Hindi heartland is more inclined towards reading books that are lucidly written around a given issue, free from academic jargon, Bengali readers are more accustomed to reading academic titles spanning multiple disciplines.

Our publication lists will be tailor made to suit its respective audience. To customise specific language lists we will select titles for each market on the basis of the theme of the book, its appeal to readers in the respective language, style of translation, etc. Also, as our books start selling from next calendar year, we will begin accumulating and analyzing appropriate sales data. This data will help us understand what we are doing right and what not – in some ways at least. We will accordingly make decisions on the titles we are doing for each group.

However, we are always ready to experiment and jazz things up a little if the need be. It is in the themes, topics, subjects etc. of the books we will publish and the forms with which we will experiment.

What is the focus of the Oxford Global Languages project and how long has it been running?

The Oxford Global Languages (OGL) project aims to build lexical resources for 100 of the world’s languages and make them available online. The OGL programme targets learners of all age groups. In short, it is a digital dictionary of diverse languages. OGL is part of OUP’s core publication programme – the programme aims to build lexical resources for 100 of the world’s languages and make them available wildly, digitally. It includes curating large quantities of quality lexical information for a wide range of languages in a single, linked repository for use by speakers, learners, and developers. This project began in 2014 and launched its first two language sites, isiZulu and Northern Sotho, in 2015, followed by Malay, Urdu, Setswana, Indonesian, Romanian, Latvian, Hindi, and Swahili. Many more will be added over the next few years.

How are these two programmes linked as well as maintain their distinct identities?

The global languages programme is aimed at building large lexical repositories for diverse language speakers across the world. Our programme will feed into this programme by helping coin new terms and as well as borrow terms from the resources that would have already been developed and stored in these repositories by experts in different languages. The two programmes thus seamlessly merge into each other as they together help develop a given language. We expect that these two projects would also help multiple stakeholders, for instance, translators, new authors, students, researchers, speakers, etc. in constantly enriching their reading and writing skills.

The new terms will be initially in Hindi and Bengali (such as say post-modern, ecology etc. ) that are being coined by translators or new authors, over time with frequent use, will get incorporated in dictionaries such as OGL as well as borrow terms from the resources. Similarly, terms that will be developed by OGL could be borrowed by translators or new authors in their works.

OUP India for many years ran a very successful translations programme that published regional language authors in to English such as Karukku and then the monographs (?). How will this newly launched programme be any different? What are the learnings from the previous programme which are going to be incorporated into this new launch?

The existing translations programme from Indian Languages to English was aimed at enriching the English speaking and reading world with the diversity in our regional literature. This programme translates works of fiction and non-fiction from diverse languages to English and it has been immensely successful in creatively rethinking our societies through exceptional works of regional and folk literature. We will not create any new imprint, all books in all languages will be included under the Oxford banner.

The Indian languages publishing programme does not aim to publish fiction or poetry at all. It will only publish non-fiction/academic works both in translation and new works in Indian languages. Our core and traditional strength has been — academic, nonfiction and general reads titles, also a bit of translations into English. This is a mandate that we follow in every part of the Press, globally – and we do not see any change during the immediate future. We will definitely do books on Film studies, yet again only non-fiction titles.

The take away from the earlier programme is that translations are always tricky business. Translations of academic titles are tricky for multiple reasons, including:

- Unlike English, formal writing styles for Hindi and Bengali are still being developed.

- Lack of terms for new concepts in Indian Languages.

- Essence of the original is at times lost in translation, retaining authenticity is tricky.

It is true that some things are always lost in translation, there is no way around it. We are trying to compensate this loss by rigorously reviewing our manuscripts by external peer reviewers —- scholars, academics, researchers, journalists, translators, who are well versed in English and Hindi or English and Bengali, with background knowledge in the disciplines of the books they are reviewing.

Such reviews are helping us develop the language further, making it lucid, readable, and accessible. Similarly, for the new books that we plan to publish under the Indian languages programme will be reviewed for their academic authenticity, clarity in expressions etc.

How many languages are you launching it in? What is to be the focus — academic, trade and children or is will OUP stick to the niche area of academic titles?

As already mentioned earlier, we are beginning with two languages, Hindi and Bengali. The focus will be serious non-fiction and academic. We are breaking the boundaries of our usual core competencies and planning to attract readers that fall outside it as well.

As an academic publisher whose business model relies considerably upon peer review, will such a rigorous process also be instituted for this project?

Yes of course, we plan to stick to our professionalism and ethical way of doing business. Language no bar. Quality is our top most priority and from our experiences in the English language programme, we understand and appreciate the value of peer reviews. The time and effort that goes into developing each manuscript in such a way is worthwhile.

How will OUP India create a demand for these titles as you are venturing into a territory that is not easily identified by readers and institutions with OUP’s mandate?

OUP as an academic press and publisher of quality knowledge resources is well identified by students, researchers, scholars, teachers across the length and the breadth of the country. Not only our academic books but our school and higher education books are frequently refereed to and stand out in quality from the rest. To say the least, we are a household name in the country. Also, we already cater to a group of readers whose primary language is not English by publishing classic texts such as those by Romila Thapar, Irfan Habib, Veena Das, Austin Granville, Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, Ramachandra Guha to name a few, which are used by students and teachers and readers across disciplines. Indian language editions of these rare classics are not easily available and students end up either reading from summary notes made by teachers or poorly done translations. Therefore an audience for our books already exists, we only need fill the gap by doing what we do best, publish quality content.

Our plans for attracting new readers have also already been discussed above. There does not exist much resources, academic and otherwise in Indian languages, as publishers we should be encouraging new authors to read and write in their native languages. We hope that our enthusiasm for this programme will also enthuse our stakeholders, mostly readers, writers, thinkers, learners, distributors. Our aim through this programme is to create new and diverse public spheres and reach out to as many readers as possible in its wake.

Will these books only be offered in print or will there also be a digital version available too?

Digital versions of our books will also be made available along with print versions and we are ensuring that we are able to launch the two simultaneously – to start with in Hindi.

If you are making classical texts from the regional languages available in English will OUP India also encourage translations from its English list into the local languages? If so, how will these projects be funded or will also these be fostered by OUP?

Our programme involves translating English titles into Hindi and Bengali within the programme. We also have plans to translate from Hindi and Bengali to English thereby ensuring that there exists a free flow of thoughts and knowledge between languages. We also hope that as we establish this translation programme, we are able to encourage close associations with groups of individual experts, institutions, and organization to develop a network of people enriched in the art of translation, such that our native languages are not lost to oblivion. We aspire to give diverse languages a new lease of life in the long-term.

Will you explore co-publishing arrangements with local publishers to drive this programme?

We are open to ideas and appropriate opportunities – that fit our quality aspirations, as well as the mission of the Press.

To maintain a quality and a standard in the translations will OUP consider empanelling translators whose skills will be upgraded regularly or will you commission work depending on the nature of every book?

We empanel translators based on their subject and language competencies and these are constantly developed in the process of translation itself with the help of continuous reviews.

What are your expectations of this project? How will you measure the success of this new project?

We expect this project to enrich readers, writers, speakers, and learners of diverse languages in our country. We also hope for it to become as successful as our English language publication and to be recognized as formidable publishers of quality books across languages and disciplines. The long-term plan is to grow and develop in these languages simultaneously with our own growth as a truly global and diverse publisher. We believe that success for such programmes can be measured in the publishing world by the kind of impact we have on our users and readers. If we inspire new and existing readership and help grow interest in good and quality content, we think we will have succeeded.

24 Oct 2017

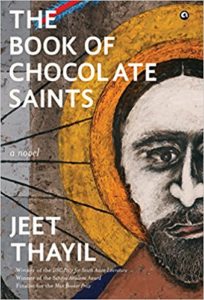

If this is a story about art then it is a story about God and the gifts he gives us. Also the gifts he takes away. God has it in for poets, that’s obvious, but the Bombaywallahs hold a special place in his dispensation. Or so I believe, with good reason. Much has been taken from the poets of Bombay. Bhagwan kuch deyta hai toh wapas bhi leyta hai.

If this is a story about art then it is a story about God and the gifts he gives us. Also the gifts he takes away. God has it in for poets, that’s obvious, but the Bombaywallahs hold a special place in his dispensation. Or so I believe, with good reason. Much has been taken from the poets of Bombay. Bhagwan kuch deyta hai toh wapas bhi leyta hai.