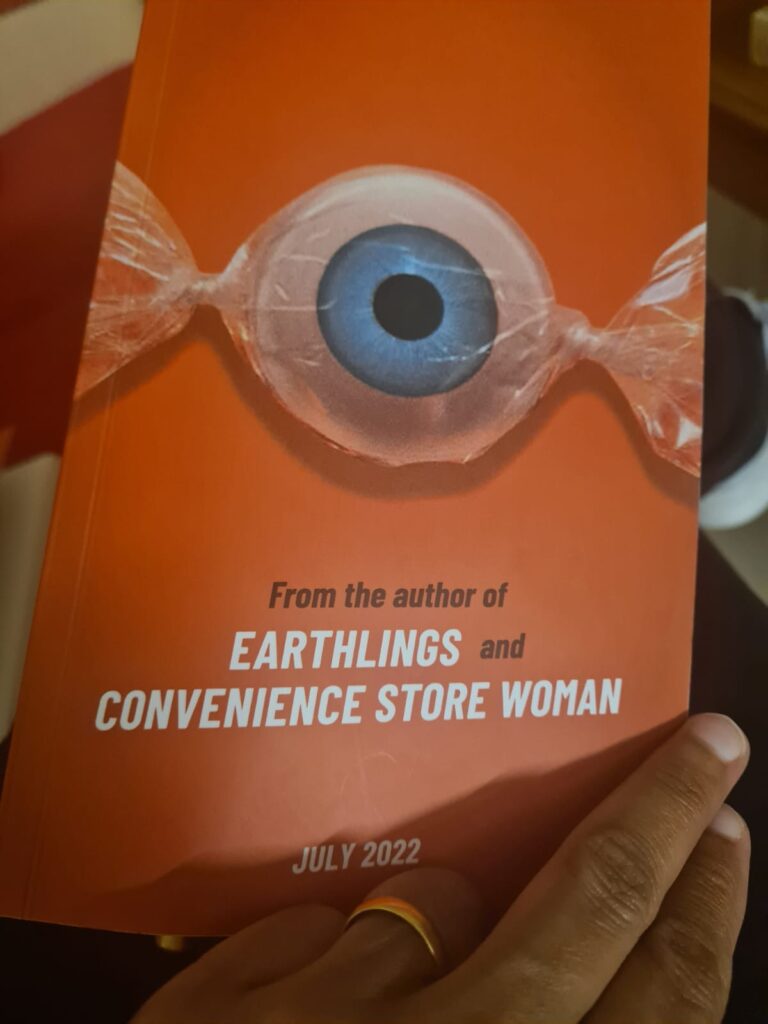

Sayaka Murata “Life Ceremony”, transl. by Ginny Tapley Takemori

Award-winning writer Sayaka Murata has sold more than 2 million copies of her book Convenience Store Woman and it has been translated into more than 30 languages. After which she published the English translation of Earthlings but in Japanese she has written over ten novels and many short stories. Life Ceremony is her first collection of short stories. As with Murata’s previous English publications, the translator is Ginny Tapley Takemori.

Sayaka Murata’s fascination with science fiction as a young girl has resulted in a unique form of storytelling. It is impossible to tell at times if the stories are set in the present times or in the near future or in an imaginative realm. “Present times” because some of the stories in Life Ceremony can be disturbing but also the actions of a cult group. Nothing can be put past human oddities. Murata has a knack of exploring human emotions to certain basic situations such as an engagement ceremony, attraction between couples, marital relationships ( hetero or same sex is not the point), procreation, love etc. But it is the angles that she explores — the traditional Japanese ceremonies that are upturned on its head such as the title story which is about a “life ceremony”. It is meant to be a wake but with a difference. Cannibalisation is encouraged where the human meat of the dead is prepared for a feast. Everyone tucks into the hotpot, the stir fry and much else that is prepared with human meat. Guests are then encouraged to find their partners amongst those seated around the table and copulate for the preservation of the human race. The children born are usually left at a centre where they are well looked after. Otherwise, parents can bring them as well though it is never clear who the father is. By today’s standards this is a bizarre concept that is very recent, less than thirty years, but no one in society finds it unethical or immoral.

Life Ceremony ( published by Granta) brings together many of Murata’s themes — social taboos, exploring sexuality, gender, love and of course, conforming to Japanese traditions. In “A Clean Marriage“, the asexual relationship of a married couple while they had multiple sexual partners outside the marriage is explored. It is not as if it is a polyamory concept but that the couple were prepared to cohabit but not necessarily be each other’s sexual partners until they decide to have a child. When they do have to have sex, they take the help of medical experts! Social and cultural taboos are explored in the “A Magnificent Spread” and “Eating the City”. The list is endless. But it is the manner in which Murata challenges the reader to think out of their comfort zones and explore imaginatevely the “what if” angle. “A First -Rate Material” is about transforming parts of the human anatomy such as bones, teeth, hair and even skin into furniture and other decorative items. The skin can be converted into a form of material that can draped like a veil or a curtain. Creepy!

A question that begs to be asked is what does the translator Ginny Tapley Takemori feel like while engaged in these translation projects? How have the stories changed her as a translator? Has working closely with Sayaka Murata influenced her translation craft? There is a surreal magical element to the quality of these stories that possibly existed in the original stories but the translator is the medium who conveys the very spirit into the destination language. The very Japanese-like nature of conformity and obedience remains at the core of the stories.

Life Ceremony is an incredible book. It leaves the reader incredulous. It is what stories are meant to do —pull the reader into the story but also make them think of the immense possibilities. It is going to be a very long time before the reader’s ability to see hair, human skin, bone, frozen foods, chemically-engineered food, fusion food, parallel realities, gendered conversations and relationships can return to an even keel. The stories in this collection are read easily once the reader’s moral compass is firmly put away. There should be no scope for judgement upon the actions of the characters or the fantastically wild imagination of Sayaka Murata.

Life Ceremony is worth reading once it is available in July 2022.

4 March 2022