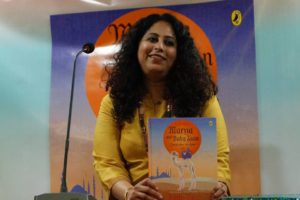

“Hijabistan” by Sabyn Javeri

Again that dark, piercing look, the shine in her pupils which made me sense that she was smiling behind her veil, as she said, “Did you ever read those books as a kid where you got the power to become invisible?”

I laughed. ‘Your veil draws more attention than a woman in a bikini.’

‘Yes, perhaps. But still. Inside, it’s my own little private world. No one knows what I look like, what I wear, how I style my hair. . .”

‘So, are you saying it makes you feel powerful?’

Sabyn Javeri’s Hijabistan is a collection of short stories exploring the idea of wearing a hijab / head scarf. It also manages to open conversations whether real in the story or imagined in the reader’s mind about the position of women in families and society. Somehow it does not seem to matter which nation the protagonists reside in – whether Pakistan or Britain – it is the mind sets that they carry with them that are critical for defining their identity. The protagonists can choose to evolve or remain where they are—caught as if in amber with a conservative outlook that literally shackles them to a god-fearing life.

Years ago, The Guardian, published an article by a young journalist who opted to wear a hijab for one week. She did this in London and documented the reactions to her dress by people on the street and her friends. It also transformed into a diary of her changing outlook. One week is all that it took for her to question so much around her. (I have been trying to locate the link for you but failed to do so.) It would be an interesting article to share given how the New Zealand Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern had covered her head while meeting the relatives of those killed in the recent mosque attack or while attending the memorial meeting. Wearing the veil is a complicated topic that has been tackled by many writers, most notably Rafia Zakaria in her wonderful book Veil.

Hijabistan is fascinating for the fact that Sabyn Javeri chose to explore alternate viewpoints while respecting those who opt to wear the garment out of choice. The multiple perspectives the author offers from the young child (“Coach Annie”) to the young wife (“The Good Wife”) to the young office goer (“The Date”) are illuminating. Of course there is the accepted view that Islam demands it of women but Sabyn Javeri presents alternative options in her fiction as to why the women choose to wear the hijab. It is a great way of offering readers’ different viewpoints. More importantly what shines through her stories are that the women are strong individuals in their own right despite donning the hijab and looking the same outwardly– a “sea of burkhas” — as the younger brother grumbles to his Api in “The Date”. What is fascinating is that the women characters come across as strong women, radiating sexuality, are feisty and exercise their individual choice. “Fifty Shades at Fifty” is a fantastic example of this. It is a story about a middle-aged wife, bound to the house, looking after her bedridden mother-in-law but exercises her freedom in choosing to read what she desires much to the bewilderment of her husband. Lovely!

Many times the stories take one’s breath away as with “Radha”, “The World without Men”, “Full Stop” and “Malady of the Heart”. Somehow the reader gets the sense that the twists will come but when they do, they are sharp. At such moments in the stories I marvelled at how much the author must have observed, heard, recorded, remembered and written down probably as she heard/witnessed it. If it was pure fiction, there would be a dull edge to it since in fiction one tends to smoothen the edges. Reality is cruel. A fine example of this is the evocative “Only in London” where Sabyn Javeri encapsulates so brilliantly the sights and sounds of Tooting, “this forgotten SW17 ghetto that doesn’t even have the novelty value of a China Town or the East End”. The tiny details about the protagonist being a desi and called out as “sister” by the locals although she really does not feel a part of the crowd. She is a desi and yet not. So confusing, so lonesome.

But truly the tour de force is “Coach Annie” and its last few lines. What a superb story! It is as if it belongs to the later batch of Sabyn Javeri’s writing, so her skills as a short story writer have been honed. There is much, much more in the story than the previous ones. “Coach Annie” has layers to it, it has details, in a few lines she captures the hostility of the boys to the head scarf to the change in attitude and their protection of their coach when the newcomers try and tease her. It is a triumph!

Hijabistan is bound to get visceral reactions to this book. Some readers would love it for the writing, many others would be either mildly amused or shocked to see mirrors of their lives in your stories and yet others would be appalled at giving women a voice, an identity and their individuality, even to go so far as exploring sexual freedom, all the while wearing the hijab — a sacrosanct symbol of Islam and its connotations of a “good” woman.

The anger at the injustice Sabyn Javeri perceives, witnesses and perhaps has even experienced has been channelled brilliantly to write these stories. It would be worthwhile to see what she crafts in future. It would also be fascinating to watch how in her future stories she sharpens her literary skills to use her words sparingly but deliver quite a punch. “Coach Annie” shows the beginnings of that skill.

Hijabistan will always have a shelf life. The issues raised are so relevant. So topical. They will never go out of fashion. Sometimes fiction achieves that which no other form of literature or conversation can ever achieve. These are thought provoking stories.

Hijabistan is an utterly stupendous book. It is! Short stories are amongst the toughest literary prose form to create. So much to pack in such few words. And yet Sabyn Javeri achieves it.

I look forward to more of Sabyn Javeri’s writing!

31 March 2019