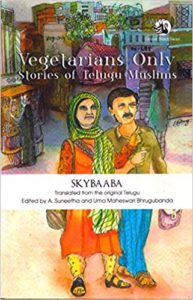

“Vegetarians Only: Stories of Telugu Muslims” by Skybaaba

I read Telugu writer and Telengana activist Skybaaba’s short stories rapidly. They give an insight into the lives of ordinary Telugu Muslims living in the Deccan and the challenges they experience — loneliness, communal prejudices, casteism, love, hostility, living in penury etc. The English translations done by a team of translators are functional but make a valid contribution to Indian literature by highlighting the diverse cultures we have in India. This collection of stories was published by Orient Black Swan a couple of years ago and has been a steady seller. In fact The Little Theatre group did a dramatised telling of the stories.

I read Telugu writer and Telengana activist Skybaaba’s short stories rapidly. They give an insight into the lives of ordinary Telugu Muslims living in the Deccan and the challenges they experience — loneliness, communal prejudices, casteism, love, hostility, living in penury etc. The English translations done by a team of translators are functional but make a valid contribution to Indian literature by highlighting the diverse cultures we have in India. This collection of stories was published by Orient Black Swan a couple of years ago and has been a steady seller. In fact The Little Theatre group did a dramatised telling of the stories.

I interviewed Skybaaba after locating him online. He very kindly agreed to do the interview. It turned into an  interesting process. He can read and understand English but is most comfortable responding in Telugu. So even if I had to chat to him via Facebook Instant Messenger to get clarifications, I would pose my questions in English and he would reply in Hindi using the Roman script. When I sent the Q& A he replied in Telugu on the document which then a friend of his, Dr. Jilukara Srinivas, Department of Telugu, University of Hyderabad, translated into English.

interesting process. He can read and understand English but is most comfortable responding in Telugu. So even if I had to chat to him via Facebook Instant Messenger to get clarifications, I would pose my questions in English and he would reply in Hindi using the Roman script. When I sent the Q& A he replied in Telugu on the document which then a friend of his, Dr. Jilukara Srinivas, Department of Telugu, University of Hyderabad, translated into English.

Here are edited excerpts:

Interview with Skybaaba about ‘Vegetarians Only’ Stories of Telugu Muslims

- How long did it take you to write these stories?

I took 11 years to write these stories. Initially I wrote poetry. But as feminism, Dalit movement in literature Muslimvadam had to be discussed in the mainstream I began to write stories. Muslimvadam got recognition as an identity movement as feminism and “Dalitism” did in Telugu literature. In that process I have played an important role. I have edited many poetry anthologies, stories collection ‘Vatan’, and Mulki, a special issue on Muslims. I had to spend lot of time and had to face a lot of pain. I lost my secured life for completing these works. I think it’s the first time in the history of Indian literature that a hundred muslim writers have come together and created an identity movement for Muslim community. To make it a ‘movement’ I have maintained a continuous interaction with many Muslim writers who have been engaged in writing lives. In 1998 I compiled many wonderful poems by Muslim poets as Zalzala. It was ground-breaking poetry, first of its kind powerful poetry in Telugu. It was the time in which Muslimvadam came up significantly. There were doubts and uncertain conditions at that time. An opportunity was there to brand Muslimvada literature as a fanatic and religious one. We tried to make it clear that Islam is a religion and the word ‘Muslim’ is a social nomenclature as Dalit. Zalzala, as a poetry collection, was an effort with this understanding. Dalit poetry has not received any opposition because it was considered as a problem of “Hindu” society. Its not the same with Muslimvadam. It can be branded as “other”. Not only that, there was a possibility that it could be termed as terrorism. I was ready to face all the charges and hardships. The poems in Zalzala criticise the Islamic and Hindu fundamentalists equally. There are multiple dimensions to the anthology. I say this collection of poems is a milestone in the literary history of India and Telugu literature too. Zalzala (1998) and Aza (2002) were two anthologies consisting of poets of two states Telangana and Andhra. A few poems of Zalzala were translated into English and Hindi. In 2002 along with another poet Anwar I also published poetry on Gujarat genocide titled Azaan. After both were received well, I started working from 1999 to 2004 and collected 52 Muslim stories from 39 different writers and published the first ever Muslim stories compilation titled Watan. Around that time, I started writing stories and started weaving my stories from different angles of Muslim life.

- At times it seems these stories particularly those about migration read more like reportage than fiction. Was that the intention?

I depicted realism of lives. I think you can’t write aesthetics when life is ending in pathetic situation. My stories in fact very have a colourful beauty in terms of content, weather, language and narrating style. All my stories end sadly. Lives are same too. In reality, most of the lives are like that. I tried to portray the lives as they are with such detail which enables the reader to find alternative solutions –that is the crux of my writing.

The two ways of finding solutions are — One, create a space in the story for the reader to engage and in understanding and let him find a solution to the problem pictured in it. Second, a solution can be suggested by author to a reader. I prefer the first way. Let readers have an opportunity to find their ways in resolving issue.

- How did the translation come about? Why were there so many translators for the stories?

Translation came really well but the team of translators and editors worked extra hard to achieve it. Because my language is special. It belongs to me too. I created my story language. I am a pro-active muslim. I belong to Telangana. Our household speaks Urdu. Street language is Telangana Telugu. But the language of educated belongs to coastal Andhra who dictated for quite long time. Even language of every magazine is costal Andhra dominated. Hence I consciously chose the language I was raised in and speak which is a mix of Urdu and Telangana Telugu.

Telangana Telugu is different from Andhra Telugu. Telangana language was dishonoured by Andhraites. I use to write Urdu words like Aapa, abbajan, bhaisaab and etc. I kept Urdu sentences for dialogues. For the nativity I used familiar Urdu words at the outset of story. It was to suggest that dialogues are going on in Urdu. “Zaldi Zaldi Jani is going towards Edgah” – it’s a line in a story. Zaldi, Zaldi, Edgah, and Jani are Urdu words. Telangana words like dikk’, nadustundu, Jebatti, Adaada, and chestunnay are mixed with Urdu words to form beautiful sentences.

So it came out as special language. Translators had a hard time translating my stories into English. Similarly, editors had to edit it precisely to get the feel of the language and content. They had to consult me also many times on that. My stories have depicted vulnerable conditions of Muslim woman. These characters will haunt after reading. For this reason editors have selected 5 famous women translators who have fabulously grasped the feelings of women characters in the stories. This was a big project which took three and a half years to complete.

- Why did you include a glossary in the book instead of including the meaning of the words within the context of the story, as is largely practised now in modern translations?

Muslimvada literature has started a trend in using Urdu words. Readers will look towards the Muslims in their neighbourhoods with curiosity. So we came to a conclusion that meanings of Urdu words should not be given immediately We thought this method will create interest among readers. We followed the same for English version too but publishers asked us to provide at the end.

- Were you involved in the translation process? If so did you work on the stories for the English version or do they all remain true to the original stories in Telugu?

I’m not acquainted with English language. Complete rendering of my stories has been carried out by the translators and editors. They have discussed with me about the atmosphere, context in which words are used and sense of the certain Urdu terms too. I feel the translators have done a tremendous job and have exceeded my expectations.

- Are any of the stories autobiographical? I get the sense that the story about the young couple house-hunting as well as “Urs” are about you. I may be wrong.

Your perception is correct. Many of the stories are made out of my experiences. It means many of my stories are autobiographical — “Jani Begum”, “The Wedding Feast”, “Sheer Khorma” , “Life in Death” , “Urs” and”Vegetarians Only” too. My wife and I, in fact, have experienced all the situations while searching to rent a home. “Vegetarians Only” which is about a young married couple house hunting but constantly being denied accommodation as the landlords did not want beef-eating tenants and preferred vegetarians. Ultimately it was a dalit family willing to rent a tiny room to the couple. I wrote this story as a reflection of the prejudices Muslims experience on a daily basis. Now this story is being taught as part of the post-graduation syllabus for 400 students in Kakatiya university.

- Why did you choose the pen name “Skybaaba”?

I’m Shaik Yousuf Baba. When I was in school I would write my name as “Skybaba”. “Sk” from Shaik, “Y” from Yousuf which made it sky and then I added “baba” to it. I introduced myself as “Skybaba” to literary friends. My first poem was published with this name. From then it has been my name. many have suggested me to keep Yousuf. But I like Skybaba. You know, when I tried to use it for Facebook, and for a blog, it was not available. So, I have added a syllable “a” making it “Skybaaba”. Now nobody can use it in social media as a name for a profile. We used the same in translation too. In two Telugu states, people will recognize me with “Skybaaba” only.

- In the introduction it is mentioned that your father was well-read but most of the women were uneducated. I am struck by how educated your father was and how many stories he read. How did this disparity in education levels between him and his wife come about? I ask since some of the women you have in the stories are educated even if it means fighting for the space.

My father studied up to 9th standard but he was able to read in Telugu, Urdu and Hindi. He read many novels in the three languages. I use to listen him while he narratied the stories to my mother. I also use to listen to my mother tell the very same stories to the neighbours. In my father’s generation there was no opportunity to get education for woman. You cannot see the identity movements at that time. I mean that social justice and equal rights to backward classes, untouchables and minorities. It was a result of awareness. It does not mean that opportunities have come to me. But the Muslim community has received something like Muslim reservation out of my struggle. In Telugu, it was started before our generation. Like me, many of us have reached this stage because of identity movements. It is the reason behind keeping our stories as lessons to the students and reason for conducting researches on our literature.

- There is a reference to the anthology of 52 Telugu Muslim stories Watan: Muslim Kadhalu ( 2004) by 39 Muslim writers. Is this available in English?

No. It’s not available. It is as yet to be translated. It was a result out of my five years hard work. It contains 400 pages. For this I travelled two Telugu states and met Telugu Muslim writers to persuade them to submit their stories. I compiled it with good stories after editing and making writers to rewrite some stories. With this collection of stories even the movement of Muslimvadam was received well and its situation got changed. A lot of change occurred in the expression of stories. A lot of people appreciated it. One of my critics told me to keep the book available in the market always. So that non-Muslims can learn the lives of Muslims who are the equal sufferer of poverty, violence and humiliation as other marginalized sections. By reading this book, the hatred which is propagated against Muslims will reduce. Misconceptions like Muslims are anti-nationals, terrorists and foreigners will be erased from the psyche of masses. People will realize that Muslims are their friends. Muslims like any other community experience poverty, unemployment, love and affection.

- Please tell me more about how you came to be a writer. I know this is a clichéd question but after reading this book and reading the notes in the book I want to know. I am impressed by one of the small jobs you explored was a “book-renting shop” (why don’t you call it a library?), becoming the editor of the literary page of Telugu daily Andhra Jyoti etc.

The uncompromising nature of my mother, courageous nature of my father, grand mom’s different integrity and commitment, my village Kesarajupally’s nature, my close friend Janardhan’s atheism, Parasharamlu’s experiences with untouched social system, my keen observations, and dedication, extensively reading habit from childhood, stories, novels, poetry of woman’s issues, etc all have shaped my personality and integrity. I have a great respect and sympathy for women’s issues and problems. My love, failure, discontinuity of education, poverty, failures in business have made a good writer. Everyone cried after reading my stories. As an activist I have attended thousands of meetings and visited a lot of villages so that I became mentally strong. In a single word, I stood up because of Sufism which I have internalised and my inherent nomadic nature.

- You have started several literary magazines – “Telugu Dalit Voice” ( 2005-2006), “Mulki” ( 2002-2004), “Chaman” ( 2006-2007) and “Singdi” ( 2010-2011). Why did you feel the need to start a literary magazine? How were they different to each other? How did these magazines find their audiences? What did they contain?

Yes, I have started my literary magazines and encouraged others to start. I have also worked for many small magazines too. For the reason of mainstream media which is not supporting Dalits, Muslims and Telangana issues. Now the situation has become worse. In such a situation, I tried to disseminate the ideas and information to educate the communities. “Dalit Voice” is all about Bahujan politics whereas “Mulki” and “Singidi” is about Telangana Movement. A special issue of “Mulki” and “Chaman” have been brought out to sensitize the readers about Muslim’s issues. As an activist I tried to make them available at public meetings, gatherings and in serious book points. Useful information, interviews and articles for the social movements were given priority in the publications. They helped readers out across the two states of Andhra Pradesh and Telengana.

- Is Nasal Kitab Ghar your publishing house? Does it still exist?

Yes, it’s been working. It’s my own publishing house. So far, I have brought 16 books out. They are very valuable as no publishing house came forward to print the Muslimvada writings. Even NGOs were not agreeable. So, I have established Nasal Kitab Ghar. Isn’t it great to record a victim’s version? Is it not valuable? I have recorded diversity of Muslim community and its social and economic situation. I know some of the issues like burkha, parda, caste structure among Muslims which I recorded in anthologies will not be received well even by our own community. Yet these stories have their relevance in Telugu literature. Nasal Kitab Ghar will be there till my last breath. I will bring wonderful books forward.

- Why did you feel the need to have a strong Muslim identity to define your literary activities such as Muslimvada poetry and the short-lived Muslim writers’s forum Marfa ( 2003-2004)? Is the Telengana writers’ forum Singidi ( 2010) which you co-founded also with a strong Muslim identity?

From 1995 feminism and the Dalit movement came forward with a strong ideological base and argument. I and some other Muslim writers were inspired by these movements. We launched Muslimvadam. I worked very hard for the movement. All the important collections of writings have been published by me only. We have provided a view to look into and understand the Indian majoritarian social order. It is Muslim view point. We tried to educate Muslim community to think in terms of social and political. We also sent a message to mingle with other communities which are struggling for justice. We made them to realize that all the SC, ST, OBC, MBC literary movements are brotherly things to Muslims. ‘Haryali’ Muslim Writers Forum, ‘Marfa’ Muslim Reservation Movement intended to do the same. As a founder and leader of these organizations I worked as a key person. Unlike feminist and Dalit movement there was no support readily forthcoming for Muslimvadam. I had to bear the brunt of all the burden. I had to put my security at risk. There were threats to me from Hindutva groups but I persevered and worked steadily for years. I worked in Singidi as a Muslim representative among SC, ST, BC and women representatives. Singidi was a collective voice of oppressed sections. Dalit, BC, Tribal and Muslim literary movements have an understanding that all these communities have same roots and divided from one stem. It’s an indigenous perspective. It’s the base for these movements. It extends the concept of brotherhood among victims.

- What is the Nilagiri Sahiti group?

I see Neelagiri Sahiti as a “mother” institution since it was instrumental in shaping me as a poet. It taught me what literature is. I attended its inaugural meeting and then after I worked as a secretary for five years. Dr. Sunkireddy Narayana Reddy was its founder who was a Telugu lecturer. He is a famous poet, critic, cultural historian of Telangana. He founded many literary organizations.. He is my literary mentor. With his vision and support I have become an uncompromising writer as I have my commitment towards oppressed communities. I know there are many opportunities for the writers and activists who surrender to the state. I never thought of working with the State which denies the basic human and civil rights to Muslims , Dalits, OBC and Tribes. So, I was branded as a stubborn and headstrong poet. I may be branded in any manner but I will not abandon interests of my communities. We have organized number of programmes which have helped me grow as a powerful writer. I learnt many ideological issues from debates, conferences and talks organized by Nilagiri Sahiti. Eminent poets, writers, and intellectuals were invited to monthly and weekly meetings.

Buy the book here or by clicking on the book cover image.

27 July 2017