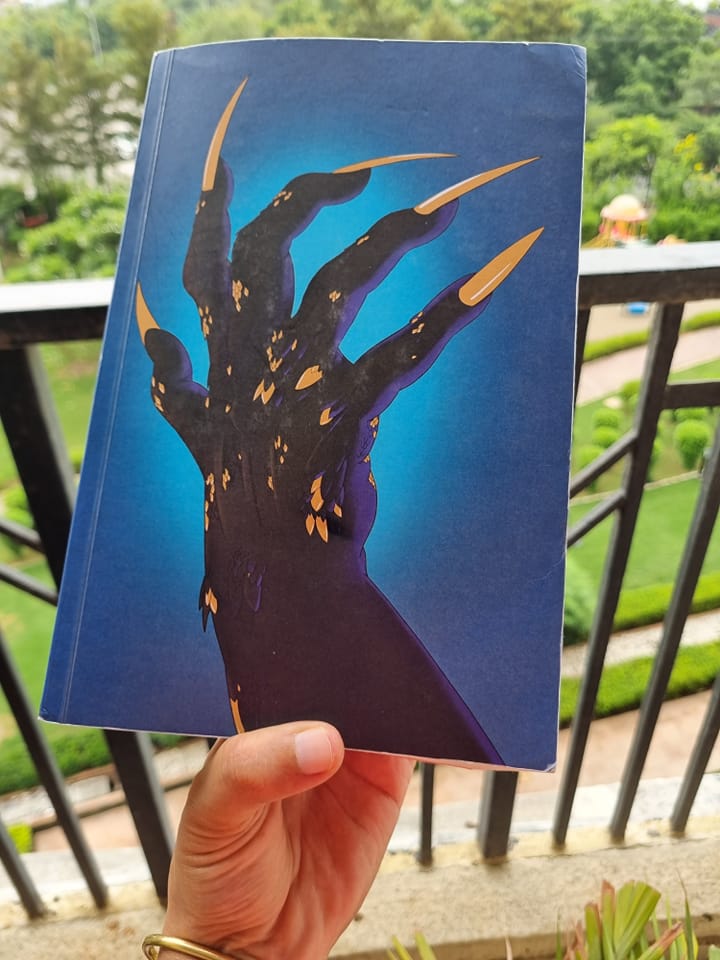

Mariana Enriquez’s “Our Share of the Night”, translated by Megan McDowell

[ I posted this on Facebook on 20 Sept 2022]

Our Share of Night is an extraordinary book by Mariana Enriquez. It is partially set in the period coinciding with military dictatorship of Juan Peron but it is a dark fantasy. Booker shortlisted Mariana Enriquez is an Argentinian political journalist and writer. Her fictional writing is explosive, bizarre, macabre, mesmerising, fantastic and gripping. It is very discomforting to read even if it is fantasy since the harsh reality of the political horrors as the backdrop are very unnerving, yet the mind processes it all. This is her debut novel that has been translated into English for the first time by Megan McDowell. This incredible literary duo have already shared their powerful chemistry with previous publications such as the short story collections: “The Dangers of Smoking in Bed” and “Things We Lost in the Fire”.

In “Our Share of Night”, this particular comment of Mariana Enriquez stands out:

“Marita had heard of Olga Gallardo before, the great female chronicler in a male-dominated world, and also a suicidal alcoholic….[it was said] that in her work, it was hard to know where the facts ended and the fiction began. And how that was mortal sin for journalists, who, though they should by all means employ the narrative tools for literature, must never employ the imagination: public responsibility and commitment to truth-telling was inalienable.”

This is at the core of her novel. I have read every single page of this 700+ novel. It has taken me a while because there are moments that Maritnez forces the reader to reflect. It is either with her observations or the very disturbing images she shares of the mutilated individuals, disappearances of children and adults, incarceration without valid reason, massacres, the womens/mothers collectives such as Mothers of the Corrientes Disappeared who were active in locating victims/missing persons, the ruthless imposition of dictatorship — ostensibly under Peron but is mostly depicted as being within the confines of Juan and Gaspar Peterson’s rich family. Peron’s horrors are a pale shadow of the fantastical magic that Juan and Gaspar as mediums of The Darkness are capable of. A magic that is horrific and merciless. It is hard to distinguish many portions of this book if it is real or imaginary or is the imagined an extension of the truth— a vile truth that is impossible for the brain to comprehend, so it distorts it? By the time the book is over, it is not easy to recollect names of all the characters in this multi-generational saga. Yet what remains with the reader is a sheer sense of helplessness in the face of authoritarianism; also with the hope that there is always a tomorrow, day better than today.

“Our Share of the Night” is a novel that plays on the title by alluding to the fictional storyline and yet by using the collective pronoun, makes the reader complicit in the atrocities experienced over the decades in Argentina. Peron’s dictatorial rule did not spare anyone, not even the poorest of the poor or the ordinary common man. The “our” in the title is chilling as Martinez uses the fictional prism to speak of a very dark period in Argentina’s contemporary political history; yet the manner in which it is elaborated upon in the novel and with quiet authorial intrusions, it is obvious that the political journalist Martinez is using her avatar as an author to warn new generations of readers that we are never really rid of such individuals. Folks with warped minds and with access to power can wilfully ruin the lives of others.

Mariana Martinez takes deep dives into rituals and character development. It is an immersion that is necessary to gauge the almost non-existent boundaries between reality and imagination. What is the truth? It is the fundamental question she is asking in many ways. It is very disturbing to realise that living under authoritarian rule blurs many of the ingrained moral barometers that humans have. Yet, perhaps there is a glimmer of hope that lies at the peripheries of these vile dispensations. And the courage to overcome these repressive systems lies deep within every individual. It is called free will. It can be exercised if so desired.

This novel can essily be used to explain storytelling and the manner in which a political journalist could write gripping fantasy, but set against a very real political backdrop. It has been brilliantly translated by Megan Mcdowell. I did pause and wonder what Megan went through while translating this book. It could not have been easy to work objectively on this project.

This book is being released by Granta on 13 Oct 2022, most likely to coincide with the Frankfurt Book Fair. Great publishing strategy. Hopefully, this book will be made available in many more book markets than just Spanish and English.

Read it as soon as you can.

24 Jan 2023