“The Journey Of Indian Publishing” by Jaya Bhattacharji Rose

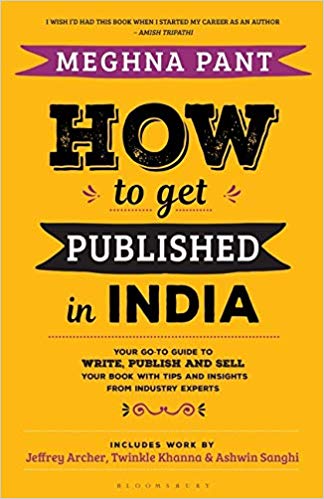

I recently contributed to How to Get Published in India edited by Meghna Pant. The first half is a detailed handbook by Meghna Pant on how to get published but the second half includes essays by Jeffrey Archer, Twinkle Khanna, Ashwin Sanghi, Namita Gokhale, Arunava Sinha, Ravi Subramanian et al.

Here is the essay I wrote:

****

AS LONG as I can recall I have wanted to be a publisher. My first ‘publication’ was a short story in a newspaper when I was a child. Over the years I published book reviews and articles on the publishing industry, such as on the Nai Sarak book market in the heart of old Delhi. These articles were print editions. Back then, owning a computer at home was still a rarity.

In the 1990s, I guest-edited special issues of The Book Review on children’s and young adult literature at a time when this genre was not even considered a category worth taking note of. Putting together an issue meant using the landline phone preferably during office hours to call publishers/reviewers, or posting letters by snail mail to publishers within India and abroad, hoping some books would arrive in due course. For instance, the first Harry Potter novel came to me via a friend in Chicago who wrote, “Read this. It’s a book about a wizard that is selling very well.” The next couple of volumes were impossible to get, for at least a few months in India. By the fifth volume, Bloomsbury UK sent me a review copy before the release date, for it was not yet available in India. For the seventh volume a simultaneous release had been organised worldwide. I got my copy the same day from Penguin India, as it was released by Bloomsbury in London (at the time Bloomsbury was still being represented by Penguin India). Publication of this series transformed how the children’s literature market was viewed worldwide.

To add variety to these special issues of The Book Review I commissioned stories, translations from Indian regional languages (mostly short stories for children), solicited poems, and received lovely ones such as an original poem by Ruskin Bond. All contributions were written in longhand and sent by snail mail, which I would then transfer on to my mother’s 486 computer using Word Perfect software. These articles were printed on a dot matrix printer, backups were made on floppies, and then sent for production. Soon rumours began of a bunch of bright Stanford students who were launching Google. No one was clear what it meant. Meanwhile, the Indian government launched dial-up Internet (mostly unreliable connectivity); nevertheless, we subscribed, although there were few people to send emails to!

The Daryaganj Sunday Bazaar where second-hand books were sold was the place to get treasures and international editions. This was unlike today, where there’s instant gratification via online retail platforms, such as Amazon and Flipkart, fulfilled usually by local offices of multi-national publishing firms. Before 2000, and the digital boom, most of these did not exist as independent firms in India. Apart from Oxford University Press, some publishers had a presence in India via partnerships: TATA McGraw Hill, HarperCollins with Rupa, and Penguin India with Anand Bazaar Patrika.

From the 1980s, independent presses began to be established like Kali for Women, Tulika and KATHA. 1990s onwards, especially in the noughts, many more appeared— Leftword Books, Three Essays, TARA Books, A&A Trust, Karadi Tales, Navayana, Duckbill Books, Yoda Press, Women Unlimited, Zubaan etc. All this while, publishing houses established by families at the time of Independence or a little before, like Rajpal & Sons, Rajkamal Prakashan, Vani Prakashan etc continued to do their good work in Hindi publishing. Government organisations like the National Book Trust (NBT) and the Sahitya Akademi were doing sterling work in making literature available from other regional languages, while encouraging children’s literature. The NBT organised the bi-annual world book fair (WBF) in Delhi every January. The prominent visibility in the international English language markets of regional language writers, such as Tamil writers Perumal Murugan and Salma (published by Kalachuvadu), so evident today, was a rare phenomenon back then.

In 2000, I wrote the first book market report of India for Publisher’s Association UK. Since little data existed then, estimating values and size was challenging. So, I created the report based on innumerable conversations with industry veterans and some confidential documents. For years thereafter data from the report was being quoted, as little information on this growing market existed. (Now, of course, with Nielsen Book Scan mapping Indian publishing regularly, we know exact figures, such as: the industry is worth approximately $6 billion.) I was also relatively ‘new’ to publishing having recently joined feminist publisher Urvashi Butalia’s Zubaan. It was an exciting time to be in publishing. Email had arrived. Internet connectivity had sped up processes of communication and production. It was possible to reach out to readers and new markets with regular e-newsletters. Yet, print formats still ruled.

By now multinational publishing houses such as Penguin Random House India, Scholastic India, Pan Macmillan, HarperCollins India, Hachette India, Simon & Schuster India had opened offices in India. These included academic firms like Wiley, Taylor & Francis, Springer, and Pearson too. E-books took a little longer to arrive but they did. Increasingly digital bundles of journal subscriptions began to be sold to institutions by academic publishers, with digital formats favoured over print editions.

Today, easy access to the Internet has exploded the ways of publishing. The Indian publishing industry is thriving with self-publishing estimated to be approximately 35% of all business. Genres such as translations, women’s writing and children’s literature, that were barely considered earlier, are now strong focus areas for publishers. Regional languages are vibrant markets and cross-pollination of translations is actively encouraged. Literary festivals and book launches are thriving. Literary agents have become staple features of the landscape. Book fairs in schools are regular features of school calendars. Titles released worldwide are simultaneously available in India. Online opportunities have made books available in 2 and 3-tier towns of India, which lack physical bookstores. These conveniences are helping bolster readership and fostering a core book market. Now the World Book Fair is held annually and has morphed into a trade fair, frequented by international delegations, with many constructive business transactions happening on the sidelines. In February 2018 the International Publishers Association Congress was held in India after a gap of 25 years! No wonder India is considered the third largest English language book market of the world! With many regional language markets, India consists of diverse markets within a market. It is set to grow. This hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2017, Livres Canada Books commissioned me to write a report on the Indian book market and the opportunities available for Canadian publishers. This is despite the fact that countries like Canada, whose literature consists mostly of books from France and New York, are typically least interested in other markets.

As an independent publishing consultant I often write on literature and the business of publishing on my blog … an opportunity that was unthinkable before the Internet boom. At the time of writing the visitor counter on my blog had crossed 5.5 million. The future of publishing is exciting particularly with neural computing transforming the translation landscape and making literature from different cultures rapidly available. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being experimented with to create short stories. Technological advancements such as print-on-demand are reducing warehousing costs, augmented reality is adding a magical element to traditional forms of storytelling, smartphones with processing chips of 8GB RAM and storage capacities of 256GB seamlessly synchronised with emails and online cloud storage are adding to the heady mix of publishing. Content consumption is happening on electronic devices AND print. E-readers like Kindle are a new form of mechanised process, which are democratizing the publishing process in a manner seen first with Gutenberg and hand presses, and later with the Industrial Revolution and its steam operated printing presses.

The future of publishing is crazily unpredictable and incredibly exciting!

3 Feb 2019