( This interview was first published on Bookwitty.com on 20 December 2016 )

Daisy Rockwell is an artist, writer and Hindi-Urdu translator living in the United States. Rockwell grew up in a family of artists in western Massachusetts. From 1992-2006, she made a detour into academia, from which she emerged with a PhD in South Asian literature, a book on the Hindi author Upendranath Ashk and a mild case of depression. Upendranath Ashk was a Hindi writer, based in Allahabad, who began publishing in pre-Independent India but soon, due to his irascible temperament chose to self-publish much of his later work. Daisy Rockwell met the Hindi writer on a few occasions in the 1990s and began translating his fiction with his permission. Unfortunately Ashk never saw Daisy Rockwell’s publications. Daisy Rockwell’s diligent dedication to the task shines through the quality of the English translations that were ultimately published. The translated literature is a pure delight to read; smooth and evocative of the early and mid-twentieth India they are set in.

Daisy Rockwell is an artist, writer and Hindi-Urdu translator living in the United States. Rockwell grew up in a family of artists in western Massachusetts. From 1992-2006, she made a detour into academia, from which she emerged with a PhD in South Asian literature, a book on the Hindi author Upendranath Ashk and a mild case of depression. Upendranath Ashk was a Hindi writer, based in Allahabad, who began publishing in pre-Independent India but soon, due to his irascible temperament chose to self-publish much of his later work. Daisy Rockwell met the Hindi writer on a few occasions in the 1990s and began translating his fiction with his permission. Unfortunately Ashk never saw Daisy Rockwell’s publications. Daisy Rockwell’s diligent dedication to the task shines through the quality of the English translations that were ultimately published. The translated literature is a pure delight to read; smooth and evocative of the early and mid-twentieth India they are set in.

Rockwell has written The Little Book of Terror, a volume of paintings and essays on the global war on terror (Foxhead Books, 2012), and her novel Taste was published by Foxhead Books in April 2014. Her translation of Ashk’s well-known novel about the evolution of a writer Girti Divarein was published by Penguin India as Falling Walls (2015), her collection of translations of selected stories by Ashk, Hats and Doctors ( 2013); and her new translation of Bhisham Sahni’s legendary novel about the partition of India, Tamas ( 2016).

How did you choose Hindi to be the language to master and translate from?

I wandered into Hindi in college and never really wandered out again. I loved learning languages and had studied French, Latin, ancient Greek, and German. I wanted something less familiar and happened to take a social sciences course with Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, who spoke of her life doing research in India, so I decided to sign up for Hindi. Translation was something one had to do anyway in graduate school, but I was fortunate to take a translation seminar with AK Ramanujan shortly before his death, and that illuminating experience has stayed with me always.

How do you select a text to translate?

It’s hard to say. Often a text chooses you, rather than vice versa. I wrote my doctoral dissertation about Upendranath Ashk, and always wanted to translate his work, though that project fell by the wayside. Eventually I took it up again because it wouldn’t let me go.

Do you have any basic guidelines that you follow while translating? For instance is it crucial to convey the authentic form of Hindi used in the language of origin or is it important to stress readability in the destination language?

What’s important to me is that the translation reads as well as the original, and that the reader in English can get the same feeling from it that the Hindi reader might (despite the vastly different reading contexts).

If the text you decide to work upon has been translated before into English, do you ever read it or do you like to approach your project with a fresh perspective?

I would never retranslate something that was already done well. I first check the existing translation against the Hindi in the opening chapter. If I decide to retranslate it, I keep the other translations at hand and consult with them, as though I were sitting among friends. Even if I think the previous translator did poorly, I recognize that he or she may see things in ways that would escape me, or know things I don’t know. Translation is a lonely business, and the other translators keep me company. I argue with them, listen to them, curse at them, and lean on them. Much of Hindi literature has not been translated, however, so retranslation is actually a rare luxury.

What has been the most exciting challenge you have encountered while translating Hindi?

Translation is almost always challenging, but rarely exciting.

What form of Hindi are you most comfortable with? Does it belong to a particular period of Hindi literature?

Because of Ashk and Bhisham Sahni, I have become really strong in 1930’s-40’s Punjabi-centric Hindi. I know all kinds of architectural details and articles of clothing and turns of phrase. Oddly, contemporary writing can be much more difficult for me.

Does translating Hindi while based in USA create any cultural challenges or is the immersion in your text so complete that your geographical location is immaterial?

It’s terribly challenging, but Twitter and social media have changed things dramatically. Much of the translating I’ve done would be difficult in India or Pakistan as well, without the reach of social media. There is much in novels of the earlier part of the 20th century that cannot be found in dictionaries nor in contemporary discourse. It’s not stuff most people know. I have to hunt high and low for definitions of some terms, and I depend greatly on my twitter friends for help in this regard.

Do you think it is “easier” to publish translations of Hindi literature as compared to when you first started in the 1990s? If yes, what are the possible reasons for this growing interest?

It is easier to publish them in India. In the US, I have yet to find a publisher for any of my translations. In India there is definitely a growing interest in translations and a growing respect for non-English language literatures. I am not sure how this happened, but I am thankful for it, and all signs point to continued growth in publication and interest.

How do you define “original text” as opposed to the “transcreations” authors such as Bhisham Sahni and Upendranath Ashk undertook with their own works when translating into English — a style not uncommon among many bilingual writers? Won’t the “revisions” to the text done later by the authors themselves be considered as “original” text? Which version do you opt to use in your translation?

I think bilingual authors should avoid translating their own work as much as possible. It seems most writers cannot withstand the temptation to alter the original while translating. They are the author, after all, so they have the right–but in doing so they deprive the English readers of the original text. At times, they alter the original beyond recognition, as in the sad case of Qurratulain Hyder’s translations River of Fire and Fireflies in the Mist. It is also often the case that bilingual people are rarely the same writer in two languages. Sahni translated Tamas himself, for example, but his English writing style was brittle and high-brow; though he knew English extremely well, he didn’t know the kind of English that Tamas would have been written in. The Hindi of Tamas is strikingly clear, succinct, and unadorned. His translation was unable to capture that. Hyder’s English was also perfect, but she clearly believed that the material must be presented differently to English readers and changed her works in sometimes very peculiar ways. And despite the fact that her English was perfect, I don’t believe that she wrote as well in English as she did in Urdu. It wasn’t a matter of being correct or not, but a matter of flow and style. In the case of the Sahni family, there was recognition that their father’s translation did not quite capture the spirit and they generously gave permission to retranslate. Sadly, Hyder’s heirs, following her wishes, refuse to grant permission to anyone to retranslate the books, so they remain off-limits to English readers, except for in their transcreated versions.

Your two creative pursuits — painting and translations can be exacting and very fulfilling. Do they in any way influence each other? For instance if you are tussling with a particularly challenging piece of translation does it get reflected in your painting and vice versa?

I’d like to think they’re connected, but if they are, the connection is not clear to me. I’ve occasionally illustrated translations or discussions of translation, but most of the time they are quite separate in my mind.

Is your preference only for literary fiction or would you try pulp fiction or even poetry in the future?

I’ve always been a high literature kind of gal. I never read pulp fiction (except for Blaft’s Tamil Pulp Fiction!) at all. There are plenty of translators who could do that, at any rate, but classics, in particular, require a great deal of reflection and research, and that’s where my niche lies. I have been translating some poetry lately though, such as Shubham Shree’s Poetry Management, and Avinash Mishra’s untranslatable poems on Hindi orthography . I’ve also been translating some poetry by Mangalesh Dabral, which has not yet been published.

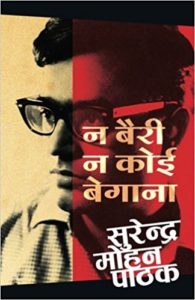

Popular Hindi pulp fiction writer Surendra Mohan Pathak has written his 298th book. It is the first volume of his autobiography called Na Bairi Na Koi Begana: Volume 1 . It documents his childhood and early beginnings as a writer. It has a generous amount of black and white photographs as well as images of the covers of his first books. Undoubtedly his fans will be mighty pleased to read this book and how he as a young telecom inspector ventured into pulp writing. The hub of this form of fiction was Meerut which coincidentally was his hometown too.

Popular Hindi pulp fiction writer Surendra Mohan Pathak has written his 298th book. It is the first volume of his autobiography called Na Bairi Na Koi Begana: Volume 1 . It documents his childhood and early beginnings as a writer. It has a generous amount of black and white photographs as well as images of the covers of his first books. Undoubtedly his fans will be mighty pleased to read this book and how he as a young telecom inspector ventured into pulp writing. The hub of this form of fiction was Meerut which coincidentally was his hometown too.