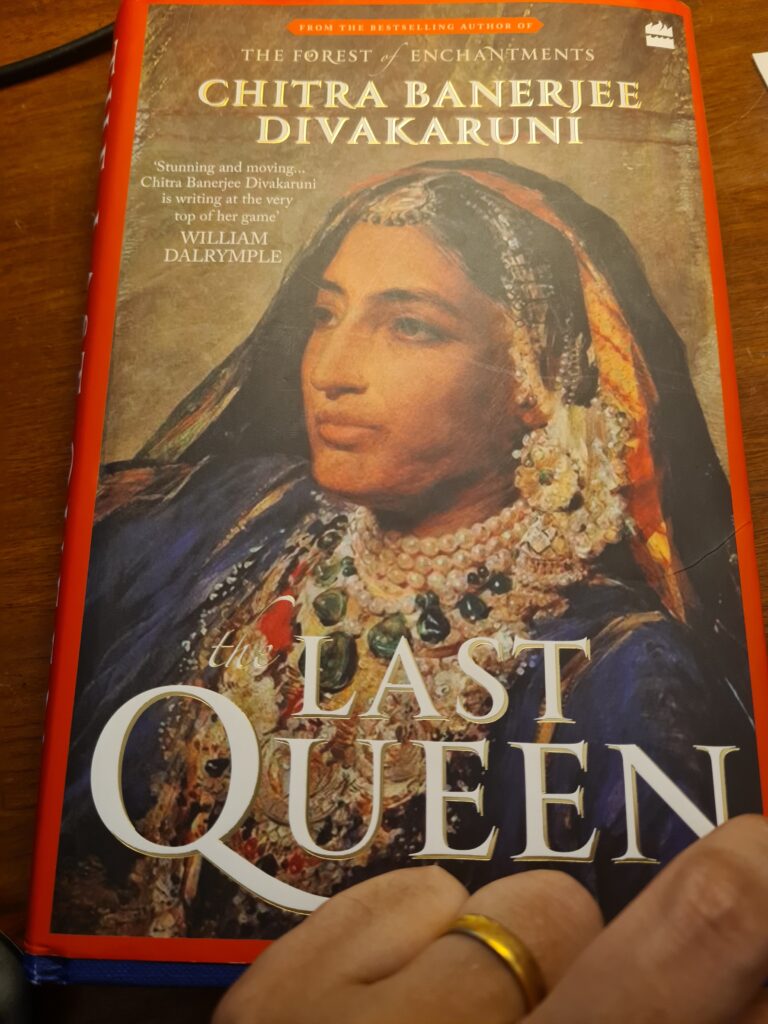

“The Last Queen” by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Chitra Banerjee Divakarurni’s latest novel The Last Queen is a wonderfully mesmerising account of the last queen of Punjab, Rani Jindan. She was Maharajah Ranjit Singh’s youngest wife and mother of Maharajah Dalip Singh, who was later close to Queen Victoria. She was also grandmother to Sophia Dalip Singh, a prominent suffragette. Given who she was and the power that she held, surprisingly little is known about the queen, except in stray references and of course the magnificently regal portrait of hers by George Richmond (1863). In fact, Chitra Divakaruni loved the painting so much that it has been used as the cover image to her novel. So, it is remarkable how much research and effort she had to put in to create this literary portrait of Rani Jindan and make her come alive. In terms of her oeuvre, I find that the author gets better and better with every passing book especially in creating women’s conversations. It could range from the conversations between the maids, hurling of insults, jealousies, love and affection etc. Chitra Divakaruni is astonishingly skilled at rescuing women from history and creating their point of view.

While reading this novel, my head kept buzzing with umpteen questions. So, I zipped off an email to her. She replied, “I value your opinions greatly, so I am truly pleased that you enjoyed it. These are great questions. Thank you!”

“Thank you, Chitra!”

Here is a slightly edited version of the interview:

- Why did you choose to write this story? Isn’t this your first novel that is truly historical fiction as it is based in well-documented facts?

I had ventured into the historical novel field earlier with a short children’s novel set around the Independence Movement, titled Freedom Song, but The Last Queen is my first historical novel for adults. I was drawn to Rani Jindan’s story when I came across her famous painting, commissioned by her son Maharaja Dalip Singh, while she was in London, during her last years. (It is this painting that is on the cover of the novel.) I was immediately drawn to it. She has such a strong personality. I could feel her power and stoicism as well as her tragic life. I could feel her indomitable will. Searching, I discovered that she had been almost forgotten by history, although her husband and her son are well known – a not uncommon problem with women. I felt a deep desire to bring her story to present-day readers as there is much for us to learn from it, on both the personal and the political arenas.

2. How much research did it entail? And how did you manage to do it during the lockdown?

The novel required a lot of research, and lockdown made researching very difficult. Fortunately, I had already gathered all the books I was going to use. But I was unable to visit the places that were significant to Rani Jindan’s life, especially Chunar Fort where she was so cruelly imprisoned by the British, and Spence’s Hotel in Kolkata, where she was finally reunited with her son, whom the British had wrested away from her many years ago. I was unable to visit her residence in London, or her samadhi in India.Lahore Qila, in Pakistan, where she had spent the most formative years of for life, was obviously out of my reach. So, I had to rely on photographs, both modern and historical, paintings and maps. this turned out to be a great boon, actually, as it gave me great visual cues to create my scenes. I was also fortunate that many of my primary sources were available online, such as the diaries of Lady Login where she writes in detail about the British opinion of Rani Jindan as a troublemaker, as well as her years in England, including a visit that Rani Jindan made to the Login home.

3. How did you manage to keep track of the timelines — the wars and the plots? Or for that matter the details about the warring factions?

I have several notebooks filled with detailed notes! At a certain point I started using notebooks for each year in Rani Jindan’s life. I also had to create many diagrams of family trees, etc. to keep all the characters and their dates straight in my mind. What made it particularly challenging was that almost every male character in the Lahore court had the last name Singh, even if they were not Sikh!

4. How did you figure out the Punjabi words in the text?

I bothered all my Punjabi friends with incessant questions! They were most patient with me. Also, my editor, Diya Kar at HarperCollins India, was very helpful. She got me a qualified Punjabi reader for the manuscript, who helped me correct any vocabulary or cultural details that I had got wrong. For instance, she made sure that the Sikh names that I had come up with for the minor characters were historically appropriate, because many of the Sikh names that we come across today were not there in Jindan’s time.

5. Post-9/11, a lot of things changed for you. I remember your telling me that the sudden realisation in how Asians were looked upon in the USA was disturbing especially in how Sikhs were targeted. The Ranjit Singh-Kohinoor diamond story is very much an integral part of Sikh history/British India. Did you subconsciously make the connections between present day 9/11 events and a fascinating slice of history? Or am I reading too much into your intentions?

The common theme of prejudice and targeted violence that appear in my post 9/11 novels, such as Vine of Desire and One Amazing Thing, are central to Rani Jindan’s story, too. Prejudice and the resultant violence occur when one group sees another one as “less human” than themselves. This was the case after 9/11, and it was the case in British-occupied India. Over and over, I was struck, by reading British correspondence of the times, as to what a low opinion they had of Indians. Even the amazing warrior, statesman and king, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was referred to, in British letters, as a one-eyed grey mouse! The violence and hatred with which the British dealt with the vanquished Indian soldiers of the 1857 independence war was shocking – they fired them, alive, from cannons. It was as though they did not consider Indians to have any rights at all. I wanted readers to understand this.

6. Your stories written after 9/11 are getting more and more sharper in your explorations of masculinity and femininity. In this book, there is equal weightage between the genders. In fact, there is less of the inner mind exploration of women that you are famous for as you did in your trademark story, Palace of Illusions. Is this a conscious decision?

There were many men that were important and influential in Rani Jindan’s life. I needed to develop them so that readers could understand her life, her world and her feelings, which often impelled her into action at once dramatic and perhaps unwise. That is why characters such as her husband Maharaja Ranjit Singh who at once her hero and her teacher; her brother Jawahar who is her saviour throughout her childhood; her lover the handsome and charismatic Raja Lal Singh; and of course, her son, Maharaja Dalip Singh, to whom she dedicated her life, play an important part in the novel. I hope I have managed to bring out Rani Jindan’s feelings and dilemmas, her passion and her pain, in spite of this new balance between men and women in The Last Queen. For me, Jindan-the-lioness (as her son calls her) is still the heart of the novel!

7. I admit though that I am a little surprised at your handling of the sati episodes. I expected more from your story. So far, you have had the uncanny ability of going into a woman’s mind, thereby offering a modern perspective. In the sati episode, although well-documented that some of Ranjit Singh’s wives and concubines burnt themselves on his funeral pyre, I was intrigued as to why did you not offer an alternative opinion. Instead, it came across surprisingly as if you were in total acceptance of the incident. Why? To my mind it was so unlike you as you come across as someone who likes to gently, quietly and with grace like to question certain practices. It is what makes your stories endearing to so many people.

The sati episodes were difficult to handle, and I gave them much thought. I had to make sure that I presented them in the context of the times, and not how I see them right now–because that is how Rani Jindan would have seen them and judged them, especially the first time she is faced with them, with the death of her best friend, Rani Guddan. It would not have been historically accurate or appropriate to give her the sentiment of a 21st-century woman as regards this matter. I wanted people to feel the amount of pressure there was on Rani Jindan, too, to become a sati. The fact that she is even able to stand strong against all this pressure says something about the firmness of her character. Later, she is horrified when another dear friend, Rani Pathani, decides to become a sati — but she understands why, although she does not agree with her. The reality, as Rani Guddan points out to Jindan, is that life was very difficult for a widow, and often royal widows met a violent end after their powerful husbands (their protectors) passed away – as we see in the tragedy of Maharani Chand Kaur and her daughter-in-law Bibi.

8. How many pages a day did you write of this novel? At times there is almost a feverish pace to this novel.

The pages really depended on how the words flowed. Sometimes I was stuck for several days (which put me in a very bad mood and was difficult for my husband Murthy because he was in lockdown with me and couldn’t escape!) Overall, I tried to pace the novel the way the times would feel, psychologically, to Rani Jindan. For instance, when she is in hiding in Jammu with her baby son, after her husband dies, time passes excruciatingly slowly for her because she is impatient to get back to Lahore. When she falls in love with Lal Singh, there is a dreamy stillness to the prose, because that’s how she feels. When the battle against the British is going on (the First Anglo Sikh War), the pace grows feverish as Jindan, waiting in Lahore, gets one piece of bad news after another from the battlefield as her generals betray her and cause the massacre of the Khalsa Army. I hope I managed to vary the pace of the novel accurately to bring out Rani Jindan’s many situations and states of mind.

22 April 2021