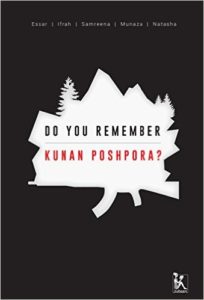

“Do you remember Kunan Poshpora?”

In the week when Kashmir is burning after the death of twenty-one-year-old Burhan Wani or as he is being referred in Indian media as “the poster boy of new militancy” ( http://bit.ly/29BWjgf ) it would be sobering to read Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? Published by Zubaan in March 2016 it is about the mass rape of women and the brutal sexual torture of men in the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora by soldiers of the Indian Armed Forces. The book also includes the text of the confidential report of the then Divisional Commissioner Kashmir Wajahat Habibullah (along with the deleted paragraphs). Since the book was published there were more developments in the case but could not be included in the publication.

In the week when Kashmir is burning after the death of twenty-one-year-old Burhan Wani or as he is being referred in Indian media as “the poster boy of new militancy” ( http://bit.ly/29BWjgf ) it would be sobering to read Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? Published by Zubaan in March 2016 it is about the mass rape of women and the brutal sexual torture of men in the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora by soldiers of the Indian Armed Forces. The book also includes the text of the confidential report of the then Divisional Commissioner Kashmir Wajahat Habibullah (along with the deleted paragraphs). Since the book was published there were more developments in the case but could not be included in the publication.

I am posting extracts from the book. The sequencing is mine.

While I was composing this blog post noted human rights lawyer Vrinda Grover posted on Facebook the following:

Our silence, as young protestors are being killed in Kashmir and many severely injured, is suffocating me.

Kashmir is a political dispute and needs a political engagement. We must protest and demand an end to this militarisation. After the 2010 killings of over 112 persons by security forces in Kashmir, 4 of us – Sukumar Muralidharan, Bela Somari and Ravi Hemadri and myself – traveled across Kashmir visted the families of those killed and the wounded. We documented the excessive and indiscriminate use of lethal force against unarmed protestors that led to the grievous loss of life; the pellet gun and catapults that caused blindness and multiple organ injuries; the hospital in Patan that was attacked by the CRPF where injured were being treated and a child shot dead in the hospital premises; children like Tufail Mattoo and Sameer Rah were killed. No FIR was ever lodged and no one was held accountable for these killings. https://kafila.org/2011/03/26/four-months-the-kashmir-valley-will-never-forget-a-fact-finding-report/

Death has rolled its dice again.”

“We knew that if we remained silent, they would do it again, if not in our village then somewhere else.” — A survivor

This book is that you are about to read is unusual, special and quite extraordinary. It spans, traverses and tracks a long passage of time — 24 years — during which the truth of the mass rape of women and the brutal sexual torture of men in the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora by soldiers of the Indian Armed Forces, was sought to be distorted, denied or buried by the Indian state and its many agencies. When a truth of this nature and magnitude is thus treated or suppressed, the quest for justice is boosted not only amongst the victims / survivors but also amongst large sections of the population; women and men, none of whom is unscathed or untouched by the mass violence surrounding them. They are in fact, witnesses.

Many have grown up in the midst of this violence; the myriad forms it takes, the fear and terror that it unleashes on a daily basis, the lies and lawlessness of the state; be it on a street or one’s home — it is their lived experience. So it is with the five young authors of this book. They were either not born or just born at the time of the ‘incident’ in early 1991.

When I met these young women in the summer of 2013 ( at the office of JKCCS, the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society) in the course of my own work on sexual violence and impunity in J&K, each one of them was poring over various documents in English or Urdu in files that were scattered open; these were the documents that told and corroborated the ‘story’ of the mass rape in Kunan and Poshpora that JKCCS had accessed through several RTIs ( right to information) that they had filed in different government departments. There were also records of the victims’ / survivors’ testimonies that these young women had procured over a period of time. I was struck by the number of documents and the amount of information that was there, it reminded me of how different it was compared to fifteen years ago when hardly any information was available, either official or unofficial, particularly regarding sexual crimes/rape. Silence and fear had prevailed then but here were these young women fearlessly articulating the problem and determined to fight the state authorities for justice and accountability.

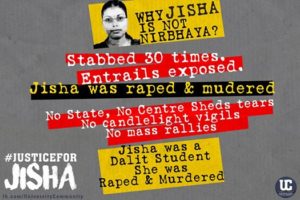

I was curious to know what had inspired them to look into a ‘case’ that took place so many years ago, even before some of them were born. What prompted them to take on this arduous journey, to undertake their frequent travels to Kupwara where these two villages are located? How did they manage to gain the trust and confidence of the victims / survivors such that they were willing to share their stories yet again, this time with a group of young, concerned women? One of them voiced it poignantly and succinctly: when a young woman physiotherapy student was gang-raped in a moving bus on the streets of Delhi in December 2012, the outrage among people was such that the entire country erupted into militant protests that demanded justice for the victim and punishment for the accused. How come the frequent rapes in J&K by the armed forces do not move the same Indians to protest this crime, not even when it is a mass rape of women as in Kunan and Poshpora? ‘We decided’, she told me, ‘that we have to raise our voice and wage our own struggle against such crimes. If we don’t, no one else will.’

This sentiment is reflected in the book when the authors ask: Is rape in India punishable but rape in Kashmir justifiable when committed by the men in uniform, the protestors of India’s honour in Kashmir? Is this the typical ‘face’ or attitude of the Indian authorities — of burying the truth and denying Justice? ‘In Kashmir, Justice is a hard thing to find’ say the authors at one point, reminding me of what a Sri Lankan woman in one of the IDP camps had once told me, ‘Justice is a dark room for us’.

…

The authors thus began to excavate the truth, by sifting it through a web of lies and botched-up investigations, by painstakingly building a bridge of trust and hope between the victims / survivors of Kunan Poshpora and the various courts of law where justice is meant to be dispensed.

These women were instrumental in re-opening the Kunan Poshpora case and demanding that it be re-investigated. They mobilized nearly a hundred women from different walks of life including a few women from their own families. Fifty of them joined these young women to file a PIL ( Public Interest Litigation ) at the lower court in Kupwara in 2013, even though the case had been closed as untraced by the JK police in 1991.

…

( From the ‘Preface’ by Sahba Husain. pp xxiii – xxvi)

The Sexual Violence and Impunity Project ( SVI) is a three-year research project, supported by the International Development Research Centre ( IDRC), Canada, and coordinated by Zubaan. Led by a group of nine advisors* from five countries ( Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka), and supported by groups and individuals on the ground, the SVI project started with the objectives of developing and deepening their understanding on sexual violence and impunity in South Asia through workshops, discussions, interviews and commissioned research papers on the prevalences of sexual violence, and the structures that provide immunity to perpetrators in all five countries.

…

Our discussions began in January 2012, when a group of women from South Asia came together in a meeting facilitated by a small IDRC grant, to begin the process of thinking about these issues. We were concerned not only at the legal silences around the question of sexual violence and impunity, but also how deeply the ‘normalization’ of sexual violence and the acceptance of impunity, had taken root in our societies.

It became clear to use that women’s movements across South Asia had made important contributions in bringing the issue of sexual violence and impunity to public attention. And yet, there were significant gaps, …

Over the three-year period since this project began, there have been amendments in the criminal law of India and the definition of sexual assault has expanded, we have gained considerable grounds in our understanding on impunity for sexual violence and consequently are better able to speak about it and fight for justice. It is noteworthy that during the recent targeted violence in Muzzafarnagar in India in 2013, seven Muslim women who were brutally gang raped and sexually assaulted by men belonging to other communities, filed writ petitions for protecting their right to life under Article 21. In a landmark judgement in March 2014, recognizing the rehabilitation needs of the survivors of targeted mass rape, the Supreme Court of India ordered that a compensation of INR 500,000 each for rehabilitation be paid to the women by the state government.

The ‘Occupy Baluwatar’ movement of December 2012 which some see as the ripple effects of the Delhi protests against sexual violence and demands for justice, had sexual violence and impunity at its centre. One of the major outcomes of the movement was the 27 November 2015 amendment broadening the definition of rape, bringing same-sex rape and marital rape into the ambit of law.

In Pakistan too, small steps forward were taken in the shape of a parliamentary panel approval in February 2015 of amendments in the anti-rape laws, supporting DNA profiling as evidence during the investigation and prohibition on character assassination of rape victims during the trial. …

The eight volumes ( one each on Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, two on India, and two standalone books on impunity and on an incident of mass rape in Kunan Poshpora in Indian Kashmir) that comprise this series, are one of the many outcomes of this project. The collective knowledge built on the subject through workshops, discussion fora, testimonies and interviews is part of our collective repository and we are committed to making it available to be used by activists, students and scholars. …

( From the Introduction by Urvashi Butalia, Laxmi Murthy and Navsharan Singh. pp ix – xviii)

*The nine advisors are: Ameena Mohsin, Hameeda Hossain, Kishali Pinto Jayawardena, Kumari Jayawardena, Mandira Sharma, Nighat Said Khan, Saba Gul Khattak, Sahba Husain, Sharmila Rege and Uma Chakravarti.

Essar Batool, Irfah Butt, Samreena Mushtaq, Munaza Rashid, & Natasha Rather Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora? ( Introduction by Urvashi Butalia, Laxmi Murthy and Navsharan Singh) Zubaan Series on Sexual Violence and Impunity in South Asia co-published with IDRC, Zubaan, 2016. Pb. pp. 250. Rs. 395

11 July 2016