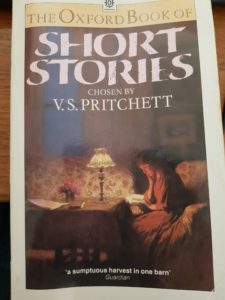

V. S. Pritchett’s “The Oxford Book of Short Stories”

An extract from V. S. Pritchett’s introduction to The Oxford Book of Short Stories, published in 1981.

An extract from V. S. Pritchett’s introduction to The Oxford Book of Short Stories, published in 1981.

*****

This anthology is a selection of short stories written in the much-travelled English language by authors whose roots are in five continents and are nourished by a variety of cultures. The period covered is from the early nineteenth century to the present day. There is no suggestion that they are ‘the best’. All anthologies are a matter of personal taste … . the bond between all of us is our fascination not only with the ‘story’ but with its relatively new and still changing form wherever it appears; and I fancy that, as a body, we are more conscious of what other story writers have done in other languages, in France, Italy, Northern Europe, Russia, and Latin America and even in what is called the Thrid World, than our novelists commonly are. In private life, story-telling is a universal habit, and we think we have something that suits especially well with the temper of contemporary life.

For my purposes two stories in English literature by Sir Walter Scott — The Two Drovers and The Highland Widow — seem to establish the short story as a foundational form independent of the diffuse attractions of the novel: the novel tends to tell us everything whereas the short story tells us only one thing, and that, intensely. More important — in American literature, Washington Irving, and above all, Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne — defined where the significance of the short story would lie. It is, as some have said, a ‘glimpse through’ resembling a painting or even a song which we can take in at once, yet bring the recesses and contours of larger experience to the mind. If we move forward to the stories written, say, since 1910 I would say the picture is still there — but has less often the old elaborately gilded frame; or if you like, the frame is now inside the picture. …

…

There is also the special difficulty of the length of short stories. The short-story writer has always depended on periodicals. In the nineteenth century, newspapers in all countries published quite long stories every week and fat magazines published immensely long ones: stories that one has to call novellas, a delightful form that may run to thirty or forty thousand words. A master like Henry James gets longer and longer as the years go by. Not only are such writers lengthy; their prose is leisurely, often sententious and delights in cultivated circumlocution and in the ironies of euphemism. The break in prose style between ourselves and our elders that occurred in, say, 1900 is also a symptom of the conflict between long and short. …

…

In the present century, now eighty years old, style, attitudes, and natural subject matter have changed. Strangely, we are now closer to the classic poetic conception of the short story as Hawthorne and Poe saw it, closer — in our mass societies — to fable and to the older vernacular writers. We are less bound by contrived plot, more intent on the theme buried in the heart. Readers used to speak of ‘losing’ themselves in a novel or a story: the contemporary addict turns to the short story to find himself. In a restless century which has lost its old assurances and in which our lives are fragmented, the nervous side-glance has replaced the steady confronting gaze. ( Short-story writers — like painters — are now in something like the situation of Goya in his art.) In a mass society we have the sense of being anonymous: therefore we look for the silent moment in which our singularity breaks through, when emotions change, without warning, and reveal themselves. …

…

Many of the great short-story writers have not succeeded as novelists: Kipling and Chekhov are examples and, to my mind, D. H. Lawrence’s stories are superior to his novels. For myself, the short story springs from a spontaneously poetic as distinct from a prosaic impulse — yet is not ‘poetical’ in the sense of a shuddering sensibility. Because the short story has to be succinct and has to suggest things that have been ‘left out’, are, in fact, there are all the time, the art calls for a mingling of the skills of the rapid reporter or traveller with an eye for incident and an ear for real speech, the instincts of the poet and the ballad-maker, and the sonnet writer’s concealed discipline of form. The writer has to cultivate the gift for aphorism and wit. A short story is always a disclosure, often an evocation — as in Lawrence or Faulkner — frequently the celebration of character at bursting point: it approaches the mythical. Above all, more than the novelist who is sustained by his discursive manner, the writer of short stories has to catch our attention at once not only by the novelty of his people and scene but by the distinctiveness of his voice, and to hold us by the ingenuity of his design: for what we ask for is the sense that our now restless lives achieve shape at times and that our emotions have their architecture. Particularly in the writers of this century we also notice the sense of people as strangers. A modern story comes to an open end. People are left carrying the aftermath of their tale into a new day of which, alarmingly, they can as yet know nothing.

The Oxford Book of Short Stories chosen by V. S. Pritchett

Oxford University Press, London, 1981. Paperback edition 1988. Pb. pp. 576

15 June 2018