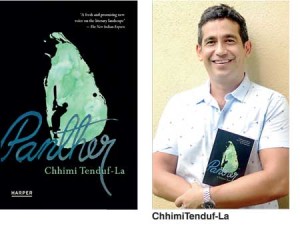

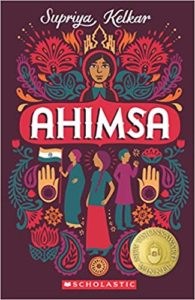

An interview with the fabulous YA writer Supriya Kelkar on her debut novel, “Ahimsa”

I interviewed Supriya Kelkar for Scroll on her debut novel Ahimsa published locally by Scholastic India — “How Supriya Kelkar wrote a novel about Indian independence that children around the world relate to“. It was published on 2 September 2018. I am c&p the interview here too. The link for the book on Amazon India is embedded in the book cover given below.

*****

Supriya Kelkar’s debut YA novel Ahimsa is about 10-year-old Anjali who is unexpectedly pulled into the Indian Freedom struggle in 1942 when her mother leaves the family to become a freedom fighter. A brisk pace and an alignment with current social sentiments makes the book particularly apt for our times. It highlights communal tensions, riots, lynchings, prison conditions, the Quit India movement, Gandhi, and the beginnings of Indian nationalist fervour. In the process, it also steps into the vacuum that is literature on the freedom struggle for children.

Supriya Kelkar’s debut YA novel Ahimsa is about 10-year-old Anjali who is unexpectedly pulled into the Indian Freedom struggle in 1942 when her mother leaves the family to become a freedom fighter. A brisk pace and an alignment with current social sentiments makes the book particularly apt for our times. It highlights communal tensions, riots, lynchings, prison conditions, the Quit India movement, Gandhi, and the beginnings of Indian nationalist fervour. In the process, it also steps into the vacuum that is literature on the freedom struggle for children.

Supriya Kelkar was born and grew up in the USA, learning Hindi by watching Bollywood films. After college she got a job as a screenwriter for Hindi films. Ahimsa is inspired by her great-grandmother Anasuyabai Kale’s role in the Indian freedom movement. Kelkar spoke to Scroll.in about her book and her writing in general. Excerpts from an email interview:

Why did you choose to write an activist-oriented novel from the perspective of ten-year-old Anjali?

I actually first had the idea to write this story as a biopic screenplay of my great-grandmother’s story about fifteen years ago. I tried and the script just wasn’t working and then decided to try it as a fictional story. I realised the more interesting point of view in the story wasn’t that of someone who already believed in the cause. It was of someone who was privileged and not yet ready to confront that privilege.

So I decided to tell the story from the point of view of a ten-year-old girl whose mother joins the freedom movement. I’m really happy with the choice. It allowed Anjali to grow and change so much over the course of the story from a young girl who is happy with the status quo, who loves her fancy clothes, and who doesn’t really understand fully her relationship with her colonisers, to one who is ready to make personal sacrifices, be an ally, and stand up for what is right, strong and confident that her voice can make a difference. It’s a pretty big arc and big awakening for Anjali.

The title, Ahimsa, is synonymous with Gandhi and the Indian freedom struggle. Yet it resonates decades later with the younger generations. What made you think of it

The title was one of the first things that came to me when writing this story as a novel, and is one of the few things that has remained from the first draft I wrote back in 2003. Since it was one of the themes of the book, it was an easy choice as a title. But my hope is that the true meaning behind the word really resonates with young readers today, as they realise how powerful their voice is, and how they can make a difference through words and peaceful action and not violence.

What changes did you make in the book over these years?

I think other than the very first moment and the last paragraph, everything in the story has changed over the fourteen year-long journey to publication. It took me a long time to be able to figure out what the crux of the plot should be. And that’s the beauty of revision. Once I was able to become detached from my words and hit the backspace key with abandon, I was able to throw out large chunks of the story that weren’t working and figure out what was. I think my characters and their arcs became stronger with each draft, and they definitely became more realistic, as I worked hard to make sure Anjali was flawed and had a chance to grow, and Captain Brent was able to grow and change too. I write on the computer, but will initially brainstorm on paper by hand. But all my outlining and writing is done on the computer.

Navigating historical landscapes at the best of times is tricky and yet you do it with such deftness. How many revisions did this manuscript require?

I wrote the first draft of Ahimsa in 2003. It was terrible and I was ready to give up, so I set it aside and went back to working on screenplays. But every year, between screenplays and other novels I was writing, I would remember Ahimsa exists and go back to it, throwing subplots and characters and scenes out and adding new things in. This went on until 2016, when it got a publishing contract. And after those thirteen drafts, I did four more revisions with my editor, so there were seventeen drafts in total.

In her memoir Ants Among Elephants, Sujatha Gidla quotes her uncle, Satyam, remembering an incident soon after India achieved independence. “A short, chubby dark boy…had a strange question for Satyam, one that Satyam had no answer to: ‘Do you think this independence is for people like you and me?’” Do you think this question remains valid even today for Dalits?

That is a really powerful quote. While I cannot speak for the Dalit community, I can speak from my experiences growing up and living in America. Here, although equality is a right and on paper everyone should be equal, it is very clear things are not the same for everyone. Systemic racism exists. Discrimination against people based on the colour of their skin or sexual orientation or religion or zip code exists. Hate crimes exist. I think the same can be said in India and in many countries.

Privileged people have to work to confront their privilege and be allies to others. Young readers and older readers alike should be aware that not everyone has the same start in life because of centuries of oppression and discrimination be it based on their skin colour, gender, sexual orientation, last name, etc. When that basic premise is accepted, people can work to address and correct inequality and injustice.

The issues of untouchability, social exclusion and women empowerment are as relevant now as they were in 1942. How did writing historical fiction help you discuss modern instances of these?

It really wasn’t until about a decade into revisions that I realised just how relevant historical fiction can be. I was stunned when things I was writing about in 1942 India were being mirrored in 2016 in America. It made me realise we have come a long way and yet we haven’t.

Women are still not considered true equals everywhere, be it in the way girls and women are sometimes treated in India or how women still do not get paid the same amount as men for doing the same job in America. People are still writing narratives for their countries, be it India, America, or anywhere else, and deciding who is included and who is excluded in their nationalism, and who is being centered. And people are still being treated as less-than all over the world. For me, writing historical fiction helps bring light to all these issues, and it is really incredible to see young readers making these connections as they read Ahimsa and see how the story can be applied to their world.

How much research did Ahimsa require?

A whole lot! I read many books and went to academic websites for the timeline and historical facts. I used my great-grandmother’s biography, Anasuyabai Ani Me, to help me fill in the gaps for the way some people thought and how they acted at the time. I consulted professors. I spoke to older family members who lived through the time period. And I relied a lot on my parents to help me fill in cultural details. I actually have several of the pictures of the real-life people, places, and things that inspired parts of Ahimsa on my website for educators and readers.

Historical fiction as a genre requires a ton of research. You have to ensure your book works on a narrative level but you also have to make sure the clothing, the food, and the facts are right. And since India is so diverse, what may be true in one part of India for one family may not be true for their relatives in a different part of India. It was part of what made the editing process so challenging. I felt like we were constantly catching mistakes, which is good, because then they could be corrected. The fact-checking was a combination of my own research, my parents and other beta readers pointing things out, and my editor’s questions that helped navigate the fact-checking.

For instance, I had based Anjali’s house on my dad’s childhood house, because much of it was like it had been in the 1940s. But because my memories of that house were from my childhood visits in the 1980s and 1990s, there were mistakes. I had always described people standing to cook in that kitchen in the book. But my dad caught that mistake and told me although the stove was on a counter when I saw the house, back in the 1940s, the cooking was all done on the floor. So I went back and rewrote the kitchen scenes to reflect that.

Writing historical fiction in the age of the internet and fake news can also be challenging because you have to make sure the online sources you use are real. It wasn’t until one of the last edits before publication, when I was double and triple checking everything, that I realised that the Gandhi quote I used in the book, “Be the change you wish to see in the world,” was incorrect. There was no proof that he ever said that, but thanks to pop culture, the saying can be found all over America on T-shirts and mugs and written on school walls, attributed to Mahatma Gandhi. I had to research a lot to find a quote that there actually was a record of that could still work in the book.

It is well-documented that atrocities against Dalits persist in India. Ahimsa is not strident, however, leaving it to the judgement of the reader to form an opinion about Dalits. How critical do you think it is as a writer to exercise one’s artistic expression in making stories available that are of utmost social concern to sensitise young readers?

I think authors of children’s book authors have a great responsibility in presenting real world issues in an age-appropriate way. As parents, we often want to shield our children from the bad parts of life. But when they are old enough to handle the information, if we continue to shelter them from reality, I think we are doing a disservice to their generation.

In America, there was (and is) a prevailing way of thinking when I was growing up, called being “colour-blind.” We were taught in school that there is no difference between people based on their skin colour and it isn’t polite to talk about race because we shouldn’t see race.

Although that may seem like a really wonderful way to think about the world, studies have shown that teaching kids to be “colour-blind” leads to children who cannot accept that there is systemic racism, or that someone with a different skin colour than them would have a different life experience than them, be treated by the police differently, or be treated by society differently.

I have experienced that first hand, where so many of my classmates walked the same hallways in school as I did but were utterly unaware of racist incidents happening every day in school. And I witnessed those same kids being unable to accept that people who weren’t white got treated differently in America. So it’s actually doing children a disservice to not talk about race and how the colour of your skin in America does affect how you are treated and the opportunities you have.

That’s why I think it is really important for children’s book authors to not gloss over real-life issues. Young readers are smart and shaping their world view at the middle-grade reader level, so it is absolutely critical that we don’t talk down to them or ignore issues of social justice, and other important issues, in books for them.

What has the response of students been like? Have the reactions varied depending upon the audience? For instance, do Americans have a different response to that of Indians or the Indian diaspora? Or do all young readers respond to the book in similar ways?

I’ve actually found that readers in America, both from the diaspora and not, and readers in India have all been able to deeply connect to the story. Not only that, so many of them have been able to apply the themes of social justice in the book to the real world, regardless of where they live. I’ve had young readers in America tell me they have been inspired to speak up because of Anjali, that they have decided to get more involved in a cause they believe in because of her, and that the story has opened their eyes to injustice around them. And I have had young readers in India tell me they know they can use their voice to change the world because of Ahimsa.

One reader in Delhi told me that she had never really paid attention to how privileged she was until she read Ahimsa. She was chauffeured to school and often tuned out any suffering she saw outside her car window because she was so used to seeing it her whole life. She told me that, thanks to the book, she will no longer ignore others’ suffering and wants to make a difference and knows she will. So although the issues children in different parts of the world (or often the same country) can relate back to Ahimsa may be different, I have found they can all find a way to connect to the story.

Ahimsa moves at a crisp pace while being packed with details, many of which are noticed on a second reading. How did you develop a love for storytelling? Who are the storytellers who have influenced you?

Thank you very much. I developed a love for storytelling thanks to the hundreds of books I read as a child, and thanks to Hindi movies. With each book I read and movie I watched, I was learning about plot and pacing and what works in a story and what doesn’t. Being surrounded by books and movies as a child, I couldn’t think of doing anything else in life but telling stories.

There were several authors whose stories I loved and learned from, like Holly Keller and Beverly Cleary. But the first storyteller who influenced me in person was my dad. He is an engineer but also wrote a lot on the side and was always introducing me to the power of words through the plays he acted in and directed for the Indian-American community we lived in. When I was growing up I saw him writing a script weekly for his Indian radio programme which airs in America and now thanks to the internet worldwide. He also wrote stories and even wrote a couple of screenplays for Hindi movies decades ago.

The other storytellers who have influenced me are people I consider myself so lucky to have got the chance to learn from. I had the great fortune of being taught screenwriting at the University of Michigan by Jim Burnstein. He is a Hollywood screenwriter and incredible teacher who taught me everything I know about structure and outlining and making sure there is logic in your writing.

I had the privilege of working for Vinod Chopra Films right out of college. Vidhu Vinod Chopra taught me so much about making sure your stories are entertaining while saying something. It was through working with him that I learned to really be ruthless in revisions, and go from an impatient novice to a writer who knows the value of revising, even if it takes years to get things right. Abhijat Joshi taught me how to shape a story, and how to really dig deep to get to the crux of a scene and make sure it hits emotionally. And I learned from Rajkumar Hirani how to fill my writing with heart and do justice to each character’s arc, while always keeping the theme in mind.

Did writing for Bollywood films inform the very visual narrative of Ahimsa, or do writing styles vary? Do you find writing for young readers is vastly different to writing scripts for movies?

I actually had to unlearn some of my screenwriting training to write novels. In screenwriting you don’t waste time describing the way someone dresses or the way a room looks or the physical way a character responds unless it is absolutely vital to the plot. That’s because the screenplay isn’t the final product.

A costume designer will decide what clothes characters wear, a set designer will decide how rooms should look, and a director and the actor will decide how they physically react to moments. Because of this, through many drafts of the book, I did not describe how my characters interact with their world to show their emotions other than in basic ways like their shoulders slumping or their smile turning down. It was only in the later edits, when my editor pointed this out, that I was able to momentarily let go of the screenwriter in me and really describe what a character was doing physically.

Other than that, I don’t find writing children’s books that different from writing screenplays. I still use a three-act screenwriting structure in all my novels, and find that the basics of plot and character are really the same in both forms of writing.

Was it challenging to find a publisher, or was it an easier process with the “We Need More Diverse Books” movement?

It was challenging. I had tried for over a decade to get an agent in the publishing world for Ahimsa and other books but I just kept getting rejection after rejection, despite my screenwriting credits. Growing up never seeing myself in a book, I never really thought a children’s book set in India could get published in America. Other than Ahimsa, for almost fifteen years, I only wrote stories featuring white families because I thought that was all that could sell.

As an adult, I saw a couple of children’s books set in India being published and it gave me hope. I’m so grateful to We Need Diverse Books and everyone involved in speaking out for the importance of diverse stories. I was lucky Ahimsa was published by Tu Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books, the largest multicultural publisher in America. And I’m lucky it’s been published in India by Scholastic. But there is still much work to be done to make sure every child gets to see their story reflected in a book.

How did the striking cover design come about? Unusually, both the American and Indian editions have used the same design. Did you have a say in it?

Yes! I love the gorgeous cover so much. It is by a UK-based artist named Kate Forrester. I love the way she uses intricate design and symbolism and hand-lettering in her book covers. I believe I mentioned that peacock feathers would be nice in the design because of their symbolism in the book and I just adore the way Kate worked them in. I also love Baba’s clenched fist, Ma holding the flag, the spinning wheel, and the plants and the reference to the garden and growth throughout the cover.

Supriya Kelkar Ahimsa Scholastic India, Gurgaon, India, 2018. Hb. pp. 308 Rs 295

3 September 2018