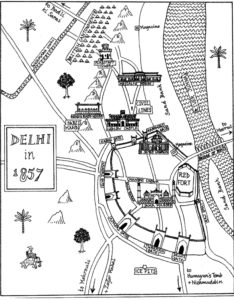

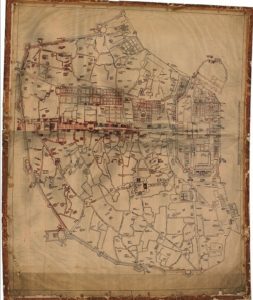

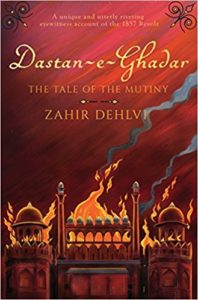

Rana Safvi’s translation from the Urdu into English of Zahir Dehlvi’s memoir Dastan-e-Ghadar: The Tale of the Mutiny was published by Penguin Random House India in 2017. Zahir’s full name was Sayyid Zahiruddin Husain, ‘Zahir’ being his poetic nom de plume. Zahir Dehlvi was in his early twenties, newly married, and living in what is now called the walled city of Delhi. He like his father was in the service of the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and they would report to work at the Red Fort. Dastan-e-Ghadar is an eyewitness’s accounts of the events that happened during the uprising of May 1857 when Indian troops employed by the British army revolted. There were many reasons for the soldiers anger but the immediate reason were that their cartridges were laced with cow and pig fat. For the Hindu soldiers, the cow is a sacred animal. For the Muslim soldiers, pigs are taboo. On 10 May 1857 the soldiers first attacked their British masters in Meerut and then marched to the city of Delhi. For decades this event under British Rule was referred to as the “Mutiny of 1857” or by many Indians as “the First War of Independence”, depending from whose perspective the events were being narrated. Now more commonly it is referred to as the “Uprising of 1857” and this is what is usually adopted by historians as well. But as Rana Safvi clarifies in her introduction that “I have used the words ‘mutiny’ and ‘rebels’ in my notes and comments, as those are the words used by Zahir.”

Dastan-e-Ghadar is meant to be a testimony to the events of 1857 and was written decades later. It is a sequence of events strung together but because it was written close to the event there are details in it that are fascinating. The chaos in the city, the confusion amongst the common people, the rumour mongering, the manner in which people fled to save themselves, the capture of the Emperor etc. All these are now well-known facts but to read the events in a contemporary account adds a different dimension to the experience of the historical event. According to historian Narayani Gupta in her review of the book in the Hindu “…it has an immediacy, and is deeply moving”. She also points out that the memoir was originally “Titled Taraz-e-Zahiri, it was called Dastan-e-Ghadar when first published in 1914. ” The book was printed posthumously from Lahore in (or about) 1914. A second edition appeared from Lahore in 1955 (an edition of which is with Irfan Habib who reviewed the book for Outlook magazine).

Yet there are liberties that the translator Rana Safvi has taken with the text which she acknowledges: “I have used my discretion to edit the text in places to keep the flow and drama of the narrative intact. ” Having said that there are some critical points about this seminal translation that are raised in the review by Irfan Habib: words like “Ghadar” and “Ghadr” have been translated inaccurately at the behest of the editors, not the translator. Later he adds:

Rana Safvi’s decision to translate the work into English is, therefore, to be welcomed. It seems a pity, however, that her rendering bears sign of some haste, so that the author’s statements in even his preface (‘Prelude’) are misunderstood. He did not indulge in “anguishing over the past and spending my time in prayer”, but “considering the past to be past and holding what had happened in the past to be just mercies from God, I let pass time in worldly ways of conduct”. He was now not induced to write because “I had [gained] access to letters and documents”, as the translation tells us, but because of the persuasions of his sincere friends and “a multitude of letters [containing such requests] having accumulated” (Urdu ed., Lahore, 1955 p. 17).

Both the academics who reviewed the English translation are of the agreement that the second half of the book where Zahir’s service in the states of Alwar, Jaipur and Tonk are possibly of greater interest than that of the events of 1857. Nevertheless Dastan-e-Ghadar is a fascinating testimony for those reading first source material about 1857 for the first time. Rana Safvi’s translation is an important contribution to Indian literature.

Following is an extract from the book published with the permission of the publishers.

****

The Surprise Attack

Just a few days had passed when another event took place. Half a mile from Kashmiri Darwaza, there was a yellow kothi near the ridge, where the purbias had set up a front and put up big guns and cannons. They were using them to inflict considerable damage on the British forces. They had two platoons and people to man the artillery present at all times. Everyone had to stay there for two watches.

One day, as luck would have it, the soldiers departing after day duty told their replacements to be careful, just in case the enemy attacked at night. The night guards took their places. Now let me tell you a few things about the night guard. It was these very men who had looted the bakshikhana and the bank. They were often in a state of stupor thanks to drinking bhang and eating kalakand and laddu peda during the day.

When they reached the kothi, they were alert at first, but when the night came and a cool breeze started blowing, they were unable to stay awake. They kept the guns at an angle and, spreading their dhotis, fell into deep sleep.

Drink bhang in such a manner that you empty all the stores

All your family is lying dead and you lie inebriated

These people were snoring away to glory. The spies took this news to the British. They informed them that the front was abandoned, the soldiers were all fast asleep and it was the right time to attack.

The British officers took two platoons of Gurkhas, one of Majwi and one of the British themselves, and rushed

barefoot down the ridge. They carried away the guns, captured the cannons and only then woke the sleeping soldiers, saying, ‘Get up, people of the faith, the goras are here.’

One soldier got up, rubbing his eyes. The Gurkhas shot his head off.

They started attacking with swords and sabres. There was tumult and crying from every side and the few who were not killed ran in a state of panic towards the city.

The Nasirabad Platoon, which had changed duty with these men, had found the city gates locked when they tried

to enter the city, as it wasn’t safe to leave them open at night. They were resting on the patri outside Kashmiri Darwaza when the ambushed soldiers reached them. After abusing and scolding them, the Nasirabad platoon told these fleeing soldiers to lie with them and they themselves lay down silently but with loaded guns.

Meanwhile, the British force came chasing them, hoping to enter the city behind them. They were unaware

of the Nasirabad platoon lying in wait. A volley of firing began and the soldiers manning the cannons on the

parapet of Kashmiri Darwaza and Siyah Burj also joined in when they saw the British forces. The situation can be best described as Khuda de bande le—only divine intervention could help.

It was difficult to save oneself from the volleys of fire. There were heaps of corpses all over.

The British troops retreated. They rushed back and took over the yellow kothi they had attacked earlier and turned their guns towards the city. These guns were now fired incessantly at the city. This continued for the whole night.

Cannons and artillery were being fired from both sides, but the Indians lost the front they had set up in the kothi,

which was now under British control. The British forces were also reinforced by troops from outside.

A senior British officer was killed in this battle and his corpse was left lying between the two forces. In the morning,

both sides tried to pick up the dead body. Cannons and artillery were firing from both sides with the purbias hellbent

on acquiring the valuable weapons that were on the dead officer.

The dead body was lying a short distance before the Kashmiri Darwaza. The two sides fought a day and a half for

the officer’s corpse. It was a matter of prestige for both of them.

The guns fired day and night and thousands of people were killed.

At last, as the sun set, one purbia reached the body by rolling on the ground. He tied one end of his turban to the

dead body and slowly pulled it behind him. He and his fellows took the officer’s pistols and sword, and, after stripping the body of valuables, left it there.

In the morning, the British saw that the body had disappeared. The battle was stopped.

The purbia brought the weapons taken from the officer and showed them to everyone in the Qila. He brought it to the house of the royal steward. He showed them to Ahsanullah Khan and told him they had fought over these weapons for two days.

I saw the weapons with my own eyes. The pair of pistols was good but the sword was invaluable. There was golden

carving on its hilt and the scabbard was black. Its colour was like the neck of a peacock, with something written on it in gold.

( Extract from pgs. 119-122)

Zahir Dehlvi Dastan-e-Ghadar: The Tale of the Mutiny ( translated from the Urdu by Rana Safvi ) Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House India, Gurgaon, India. 2017. Hb. pp. 340 Rs 599