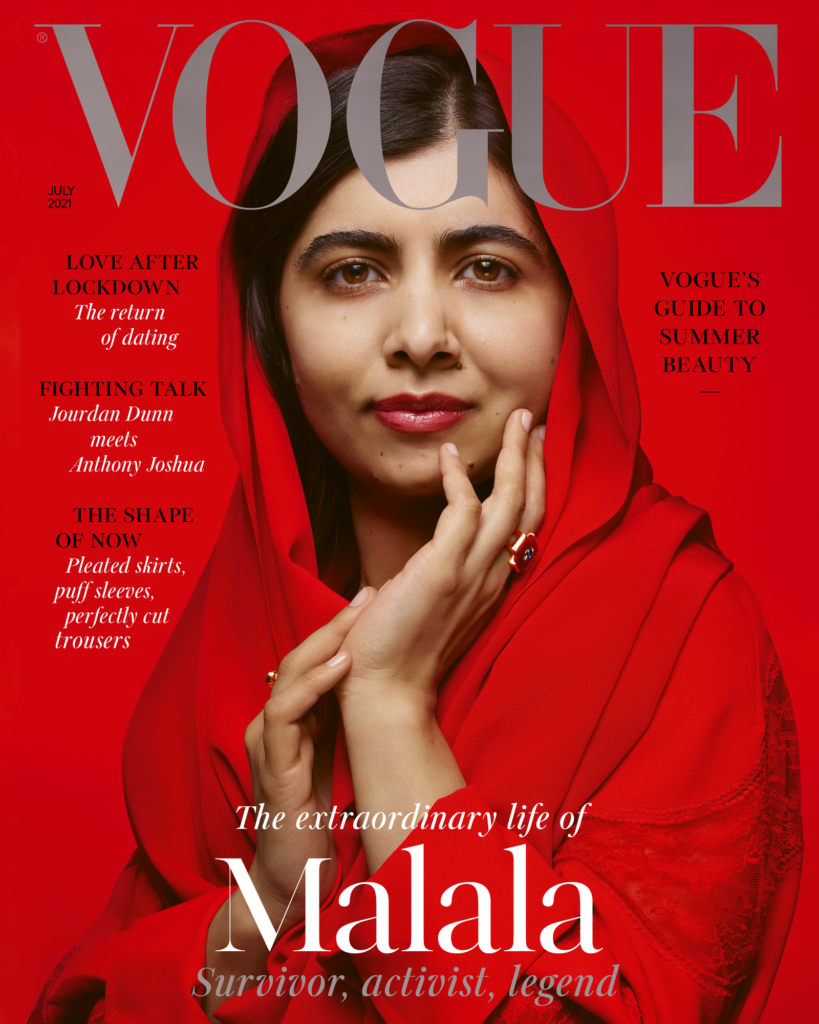

Malala Yousafzai, British Vogue, June 2021

In the June 2021 issue of Vogue ( British edition), Nobel Laureate Malala Yousafzai has been interviewed. It is a good interview as it puts the spotlight on a young twenty-three-year-old who is at the crossroads of her life, figuring out the eternal question — “what next?” Many questions are asked and a lively conversaion ensues until the silly question of relationships is posed by the interviewer. Malala’s response to it has resulted in a significant amount of trolling on social media platforms.

She isn’t sure if she’ll ever marry herself. “I still don’t understand why people have to get married. If you want to have a person in your life, why do you have to sign marriage papers, why can’t it just be a partnership?” Her mother – like most mothers – disagrees. “My mum is like,” Malala laughs, “‘Don’t you dare say anything like that! You have to get married, marriage is beautiful.’” Meanwhile, Malala’s father occasionally receives emails from prospective suitors in Pakistan. “The boy says that he has many acres of land and many houses and would love to marry me,” she says, amused.

Pakistani author, Bina Shah, wrote a fabulous post on her blog The Feminstani about this interview. Here is an extract:

Well, shit. Pakistani social media alighted upon this quote as if they were kites in the sky who had spotted a particularly tasty scrap of meat. If they were looking for something with which to bludgeon her to death, they found it: in the musings of a young woman who’s still trying to figure things out, things that confound the best and brightest of us, and the stupidest of us. “Should I get married or not, and why does there have to be marriage in the first place” is a question we’ve all asked ourselves, if we’ve got a single ounce of intelligence in our brains. (at 48, I know I ask myself the same question, and up to date neither have I found an appropriate answer nor a suitable candidate. And yet I still hope to get married some day.)

I don’t want to go into the nasty comments, the Z-list actresses who came out with statements against Malala, or the taunts of “un-Islamic” and “Zionist agent” that were showered upon Pakistan’s only Nobel Peace Prize laureate, one of its few Oxford graduates, and possibly the only girl in Pakistan to have been shot in the head and survived. They called her ugly, and that of course she wants a partnership because she’s too ugly to have a husband (in her interview, Malala said that men propose marriage in e-mails to her father all the time). The usual round of accusations and bizarre conspiracy theories — it’s a drama, she wanted a foreign passport, she was chosen by Jewish overlords to become Prime Minister of Pakistan — came out. In short, we’ve been on this rodeo before.

Also useless is to point out to the Pakistanis howling that Malala’s remarks on marriage are unIslamic that the concept of marriage in Islam, while strong and emphasized as part of Sunnah, has been fairly flexible over the centuries. A valid marriage contract written down on paper is not actually required; just a verbal agreement with witnesses will do (if we want to be very literal about it). In its early years, Islam also allowed sexual relationships with women you are not married to, but are “those whom your right hand posesses” — ie female prisoners of war, and concubines (for men only, not for women who own male slaves). A practice of temporary marriage, i.e mutah, was allowed at one point, which would then be dissolved after an agreed-upon amount of time had elapsed.

Some of these practices were established for reasons of practicality, and some of them have been abused rather than treated as the exceptions or temporary situations meant to give rights to children born out of the traditional marriage scenario. Some of these practices have been abolished, or outlawed in the modern nations where Islam is practiced. Many of these practices continue in secret. The evolution of a written marriage contract is a modern invention made in order to safeguard certain legal rights of the participants, as well as to be able to register marriages in records and databases. But there was once a time when nothing more was required for a binding partnership than two people saying in front of two witnesses that they wanted to be together as spouses.

Marriage is in short not the solid brick house that Pakistanis want to build and entrap two people in forever, regardless of their feelings, their needs, wants and desires. It is exactly what Malala expresses a little clumsily in her interview: a partnership with a door that either partner can open to leave any time she or he wants, with good reason. The Quran is clear that spouses are meant to be a comfort to one another, to have affection for one another, and to guard each others’ privacy and secrets. But it forces no one to marry against their will. If Malala is not ready to marry, and if she is never ready to marry, then she is within her rights not to do so.

In response, I wrote an email to Bina. Here is an extract from it:

It will be interesting to observe how Malala breaks her childhood shackles and really comes into her own. She is 23. So young and yet has achieved so much. For now the Vogue article has highlighted the struggle that a desi girl of her age has to face. The problem in this particular case is that Malala is a role model for girls across faiths and countries. She is a feminist icon. Whether it is the Pakistani male or any other Muslim man or any other man for that matter, they simply cannot handle such a confident young girl like Malala. Offering to marry her because the suitor owns immense property is a sham. The man is eyeing the Nobel Laureate as a trophy to forever house in his home and probably improve his social worth. Most desi men, across our fractured borders, have the same conservative mindset.

If Malala had to truly break shackles and live her life according to her terms, then it is no one’s business to question her sexuality, her choice in partnerships or the kind of arrangements she opts for. Alas, she is caught between two worlds — the public image and the conservative Pakistani Muslim community. She has to straddle these worlds.

The Vogue question about relationships was unfortunate but it holds true for any celebrity. Journalists cannot resist asking women celebrities about their sexual life and their marital status. It is what makes the papers sell. So for me, this interview with Malala, is more than her being representative of a Pakistani Muslim girl, but being an icon/representative of this new generation of girls. They have been exposed to so much more information about being empowered, what it takes to be an empowered girl, facing the violence, making choices and being articulate. This is what defines these young girls. Unfortunately, the desi girls who belong to this generation are also weighed down by other baggage such as the expectations of their families and wider circle of “settling down”.

I remember when my Dadi would go on and on about it, I always felt as if being married was like being evicted from Paradise and like Satan as described by Milton in Paradise Lost, plummeting through a neverending blackness. It is as if achieving married status was the be all and end all of life. Whereas in my reckoning, I was just beginning my life and did not need to be burdened by such questions. It really mucked up many years of my life. When I finally chose, I chose on my own terms, no one else’s. Even so, it was a late marriage by everyone’s reckoning.

You are so right about the backlash Malala has faced for her response. This is the first of many she is going to face. This silly statement of her’s will haunt her for years to come, it will be dissected in polite and not-so-polite circles as how could this seemingly polite, young girl, who (as you point out) covers her head with a dupatta, can have such strong ideas. Well, of course she can. You and I know from firsthand experience that we may dress in our desi clothes but hell, no one can ever mentally shackle us or presume to do so in any other way. It bothers folks. We don’t necessarily strut about wearing the latest Western fashions but we do have some of the most modern ideas of living. I bet you have come across many desi girls who wear the latest hip-hop clothes, but heavens, they spout the most conservative attitudes towards women.

Malala has to negotiate this space on her own but I sincerely hope that she has some good guidance regarding gender. She needs to engage in conversation and figure this out for herself. It was an unfair and loaded question. She should not have been asked it as it seems as if the interviewer was seeing only a young girl of marriageable age. Sad. The kid has won a Nobel Prize, for heaven’s sake. Give her her due. She has survived a bullet wound to the head and has managed to recover sufficiently to attend classes. How many people are fortunate to be able to do that after a head injury?

Perhaps this is what was needed. A furious questioning of these attitudes, the desire to let the younger generation express themselves freely without being burdened by “traditional” customs and this is beyond the borders of Pakistan. It is a universal truth. In many, many ways, times have changed considerably, especially for girls and women. This is a debate that will rage for some time given that a celebrity like Malala Yousafzai has expressed her opinions about it. But for now, this is accompanied by hashtags such as “Shame on Malala” trending on Twitter.

Instead of shaming the young girl, the journalists posing these prying questions about the celebrity’s relationship status should be shamed.

5 June 2021