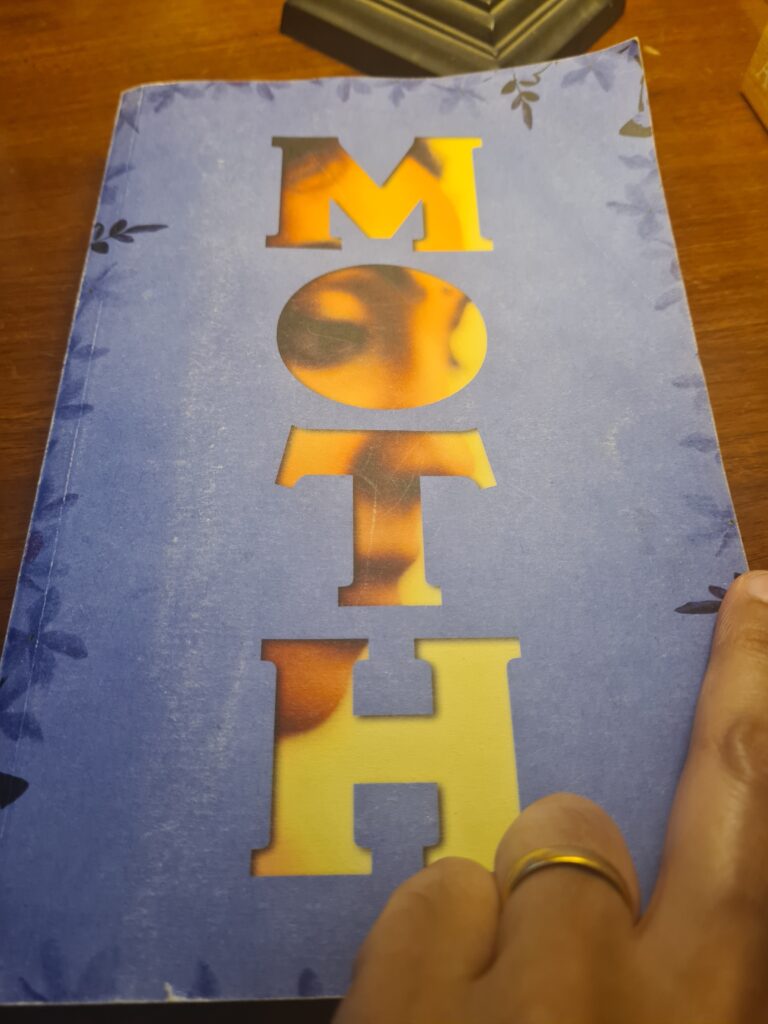

“Moth” by Melody Razak

Delhi, 1946

Ma and Bappu are liberal intellectuals teaching at the local university. Their fourteen-year-old daughter — precocious, headstrong Alma — is soon to be married: Alma is mostly interested in the wedding shoes and in spinning wild stories for her beloved younger sister Roop, a restless child obsessed with death.

Times are bad for girls in India. The long-awaited independence from British rule is heralding a new era of hope, but also of anger and distrust. Political unrest is brewing, threatening to unravel the rich tapestry of Delhi – a city where different cultures, religions and traditions have co-existed for centuries.

When Partition happens and the British Raj is fractured overnight, this wonderful family is violently torn apart, and its members are forced to find increasingly desperate ways to survive.

Moth by debut author, Melody Razak ( Orion Books), has been a surprisingly slow read for me. Usually, I manage to zip through fiction pretty quickly. More so when it is historical fiction as I have a soft spot for this genre. But this one was slow for many reasons. These ranged from false starts in attempting to read it to the many times my mind wandered after reading a section of the story. Let me explain.

Melody Razak credits Urvashi Butalia’s seminal book The Other Side of Silence for having inspired her debut novel. I can absolutely understand and recognise that sentiment. I worked with Urvashi for many years. I joined her team the day she split from Kali for Women to establish Zubaan. So, I was privy to a lot of Urvashi Butalia’s work for many years and also helped brand Zubaan. I, like Melody, and many others, had been in awe of Urvashi Butalia’s work for years. She did something fundamentally new. Of capturing the oral histories of women and families after the British left India in 1947. We gained our Independence but the people from the newly created nations suffered tremendously.

Urvashi wrote this book after she volunteered to help the riot victims of 1984. It was a watershed year for many of us living in Delhi at the time. The Indian prime minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi, had been assassinated by her bodyguards while she was en route to meet filmmaker and actor, Peter Ustinov. It unleashed the most horrific communal violence we had witnessed at that time in newly Independent India. We were still a young nation at that time. (Now, communalism seems to be a way of life.) Many, many folks were horrified at what had occurred in the capital city. It was unheard of. We had curfew imposed. The army conducted flag marches. The silence was unbearable. No one should ever have to experience the silence of living in violent times. It is very still and still very disturbing. In the far distance, we could hear mobs. We could hear sounds. We would see smoke spires in the sky. And one of the most frightening memories was to see the ashes of paper flutter down on our terraces. When my twin brother and I returned to school after those two terrible two weeks, we noticed kids in our bus who were looking dishevelled and reduced to a cloth bag carrying a few books. They had been affected by the riots for being Sikhs and had lost property and family. It was earth shattering. But we were young. It was our first experience of such violence. But for my maternal grandfather it brought back a flood of memories. Stuff we had not realised he had kept suppressed for decades.

My grandfather, N. K. Mukarji, was the last ICS officer in India. The Indian Civil Service was the administrative service established by the British. He joined as a very young man and was allocated the Punjab cadre. This was before 1947, so as a government servant he was posted in and around the then undivided Punjab. He later recalled that as a young man, he would sit with the other officers, many of whom were British, dividing the assets of the Punjab state between India and Pakistan. Many times, the lists drawn seemed arbitrary but he would meticulously minute the meetings. I am sure somewhere documents exist with his neat signature. He also used to tell us about the migrant camps that were set up. For many years, the refugees of 1947 were considered to be the largest mass migration ever recorded in human history. It was unprecedented. There were no rules or policies governing or guiding the officers on how to manage this massive influx of people. He used to tell us of how his signature was forged and converted into stamps. These forgeries were then used to stamp documents of the refugees so that they could use them as valid papers to migrate. Some left overseas too. My grandfather was well aware of these forgeries but the administration was so overwhelmed by the number of people that needed looking after that he turned a blind eye. And if you ever knew him, he was such an upright officer that this act upon his part was so unlike him. He and his colleagues worried about the spread of disease. Cholera and typhoid that still plague large refugee settlements were the bane of their existence even in the 1940s. The only difference being that there were no UN forces or other humanitarian aid organisations to help manage the healthcare of the refugees. There was no organised camp. So, the relief of the onset of the monsoon, literally washed the camp, is something that I still recollect in Nana’s voice. He has been gone for more than two decades but his relief, as if it was a God sent gesture, is something I will never forget. So, the descriptions of the refugee camps in Moth brought back memories of these stories. I could not help but think that the perception of the refugee camps of today that are to a fair degree “organised” because of the aid agencies, was not the case at that time. And this was one of the depictions in Moth that bothered me, the pell mell in the settlement. Instead, the description seems to suggest that it is fairly orderly. It was as if the image had been created from the modern images of refugee camps.

Just as these memories came flooding back for my grandfather, so did it happen with many victims of the 1984 riots. The victims were Sikhs. The community to whom the PM’s assassins belonged. Urvashi too is a Sikh. She too had family in Lahore and in India. In fact, when I went to Lahore in Nov 2003, I went in search of the house that belonged to Urvashi’s family and discovered that it was in the process of being pulled down. So, I brought back pictures of it for her.

There were many, many reasons why Urvashi was affected by the 1984 riots. But working in the refugee camps of Delhi, listening to stories, being a feminist, she realised the importance of recording these stories. Oral history testimonies were being done in our country even then but not necessarily by individuals at this level. Urvashi’s work is pioneering for many reasons. She explored her family’s history and unearthed many more stories in the process. It has had a huge impact on the way Partition stories are read.

Melody Razak picks on a few of the stories such as the women jumping into the well, the abduction of girls/women and taking them away to the other side (since then established as a regular form of persecution of women at times of conflict), the problems of documentation etc. I found it particularly interesting that while Melody Razak has been deeply moved by the incidents recounted in The Other Side of Silence and of course, for this novel, may have done some independent research, Melody has been unable to describe the traumatic incidents. I found that curious as that it is often noticed in the victims that they are unable to recount the actual event. There are mechanisms by which they protect themselves, one of them is to talk about the act in the third person or distance themselves in the plot. Melody does exactly that — distancing herself. It indicates how deeply moved she has been by the testimonies/stories of the events of 1947.

By the way, the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi whom Melody mentions, Nathuram Godse, was sentenced to death a few years later by Justice G. D. Khosla. Again, another upright officer who opted to join the judiciary once India became an independent nation. He wrote about the trial of Godse. It is freely available as a booklet online. I met Justice Khosla. He was a friend of my grandfather’s. But by these acts, I feel as if I have been close to history. (Does that statement even make any sense?)

Melody Razak gets the grief at the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi very well. I recall meeting people who remembered that day very clearly. This and later, Jawaharlal Nehru’s death. Everyone could recall what they were doing at the precise moment that the news broke about these deaths. The collective grief that was felt at Mahatma Gandhi’s death has been brilliantly captured by Melody.

But the reason why I had so many false starts to the book were because of the tiny historical inaccuracies in the opening pages. I can only recall one at the moment. She refers to Amul chocolates. Well, they did not exist till many decades after Independence. Amul is a dairy cooperative that was set up by Nehru under his modern India plans under the leadership of Mr Verghese Kurien (again, someone whom I have met). The chocolates came much, much later. So, this fact could have been checked. There were also spelling errors that annoyed me such as getting the name of All India Radio wrong and hyphenating “All India” or referring to the hot winds that blow in summer as “Lu” instead of as “loo”. (It is a hot wind similar to khamsin.)

I can see why Melody Razak has been showered with praise in the media and has been recognised as one of the debut novelists of 2021 by The Observer. She has a great sense of storytelling. Her pace is fantastic. She knows when to slow down her writing tempo or speed it up as per the requirements of the plot. Her characters are so alive. She is able to move freely between the Muslims and the Hindus and describes them well. Alma’s grandmother is particularly vile. To create evil in a person who is mostly ignored by the family, is quite a creative achievement. But alas, she is also so familiar. We have all come across such characters at some point in our lives. Melody also manages to share only that much of the back story of the characters as is relevant to the main plot. Again, an admirable quality as many debut novelists tend to get hijacked by their characters and create unnecessary tangents to the story. Whereas in this case, whether it is the stories of Dilchain, Fatima Begum, Ma, Bappa or even Cookie Aunty/Lakshmi, Melody shares enough to make them rounded rather than flat characters. There is no need to know more about them.

I had reservations about the extremely feminist angle to the storytelling. It was sort of unbelievable that these narratives could possibly have existed in 1947/8. It seems as if a very modern structure of feeling has been superimposed upon the past. It does not sit well. But then it brings me to the crux of literary fiction. At what point as Salman Rushdie calls it, does fiction “lift off” from the truth and begin a story of its own? Somewhere the writer has to be given the leeway to let their imagination fly. The reader too has to go easy on the writer for letting them tell the story in their own way. Perhaps I found it uncomfortable, even though I more than heartily agree with the feminist sentiments, because of the amount I know about the events of 1947. But the moment I sort of let myself go and just read the story for what it is, I realised it was the only way to “get into” it and enjoy it. Also, having read a lot of historical fiction recently has been doing this — of revisiting past events and imbuing the women characters with a strength and a personality with a very modern touch. It works for modern readers. And if historical fiction is being redefined today as historical events providing only a backdrop to the storytelling, then I suppose we have to make our peace with it. It is fine.

As for the sisters, Alma and Roop, they are incredibly well-created. Although making Roop cut off her hair, roam around naked and wear her father’s trousers whenever she needed to step out seemed a bit farfetched for a five-year-old. But then who are we to argue with the bizarreness of life under conflict. Or for that matter now, during the pandemic. That was another thing that I found so eerily parallel to Moth — our reality of rationing food given the lockdowns and irregular supply of provisions, not sure when to step out (in Moth for fear of communal riots and today, for fear of getting infected by the Covid-19 virus), creating community kitchens (in the novel for refugees and in modern life for migrants who are going home), etc.

As is fairly evident, Moth has triggered many memories as well as made me respond to the book in a manner that I did not think it would do. So there in itself lies the answer of a good emerging novelist. Moth is an extraordinary immersive experience and I am glad I read the novel.

3 July 2021